A new financial entity – part nonprofit, part for-profit – is being pushed as the next great way to increase the philanthropic and commercial funding available for youth-serving and other social projects.

The corporate structure is known as a low-profit limited liability corporation – or L3C – and it is structured to maximize the use of “program-related investments.”

So far, this new corporate form is legal in only one state; this spring the Vermont Legislature approved a bill allowing the creation of L3Cs, and Gov. Jim Douglas (R) signed it into law in April. Other states are considering similar legislation, according to Bob Lang Jr., who heads the Mary Elizabeth & Gordon B. Mannweiler Foundation in Cross River, N.Y.

|

|

Bob Lang |

So what could this mean for youth work?

The Issue

U.S.-based foundations, required to spend at least 5 percent of their assets in a given fiscal year, have two basic options for spending the money. They can make grants, the classic relationship in which a funder loses assets and grantees gain them; or they can make program-related investments (PRIs), for which the foundations expect to be repaid. Essentially, PRIs function as loans.

Several large foundations have embraced PRIs and created divisions to handle them. These include the Ford, Annie E. Casey and John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur foundations. The Foundation Center estimates that only a few hundred foundations make PRIs, and that only one-third of those foundations make them on an annual basis.

That’s unfortunate, contends Americans for Community Development, a project of the Mannweiler Foundation and the chief proponent of L3Cs, because a PRI is more fiscally prudent than making grants. Giving out money that is eventually repaid, even at low or no interest, means the foundation will have that money to spend again in another fiscal year.

Philanthropy experts cite two main reasons that PRIs are not more popular. First, if the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) decides that an investment made this way is not related to the program, it can assess a financial penalty against the foundation. To avoid guessing what the IRS might do, a foundation can get a “private-letter ruling” from the agency each time it plans to make an investment. But that process can take more than a year and typically requires legal fees, and the IRS charges $8,700 for each ruling.

|

|

Suppose a foundation initiated an L3C to develop workers in a community with two large furniture manufacturing companies. Here is a look at what various L3C parties might put in, and what they might expect to get out of that investment. |

The more fundamental reason PRIs aren’t more popular is a lack of institutional knowledge about the PRI process.

“There’s growing interest among foundations about learning about PRI-making, so I think it’s part of the field that’s going to grow,” says Norah McVeigh, managing director of the Nonprofit Finance Fund. “But it hasn’t become institutionalized across the foundation community.”

L3C proponents believe they can address those concerns.

How L3Cs Work

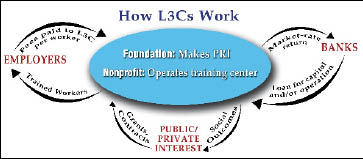

A foundation can form a limited liability corporation by itself, or with other entities, that carries a special L3C designation. This means that the corporation expects to yield some profit, but that its primary reason for existence is to do social good.

A hypothetical example: A foundation and nonprofit both see a need to develop the skills of young workers in a county where the pre-eminent industries are furniture-making and child care. The nonprofit has the staff expertise to start training youth, but needs a location, materials and equipment.

The nonprofit would be able to repay the set-up money from several revenue sources: tuition, fees for service from the county, and reimbursement for training from area employers who hire the trained workers.

The foundation and the nonprofit form an L3C. The foundation makes the initial investment (a PRI), which is used to buy a vacant warehouse for the training center and to purchase machinery and supplies. The PRI is a high-risk, low-return proposition, because the foundation will be repaid only if the social mission succeeds. That would probably happen over a long period of time, and the interest rate is lower than the rate for standard loans.

It is in this type of situation – when a lot of cash is needed for startup capital – that PRIs can help a foundation make a commitment. At a 2006 panel discussion about making PRIs, the Casey Foundation’s director of social investments, Christa Velasquez, says the average Casey grant is about $75,000, while “our typical PRI is probably about half a million to a million dollars.”

Once a foundation creates an L3C, it can make various program-related investments. In the above hypothetical example, if another nonprofit proposes to undertake similar training for workers in another field, the foundation could fund that effort through the same L3C.

Lang, of the Mannweiler Foundation, believes that the greatest benefit of L3Cs will be increased commercial investment in charitable ventures.

“No venture capitalist is going to give money at a low return rate,” Lang says. “By taking that first risk” by investing through an L3C, “the foundation improves the credit of the risk of the venture,” making it safer for others to invest subsequently.

The arrangement offers a safe bet for banks and lenders, McVeigh says, because “while the foundation takes the risk” by providing the investment that gets repaid at a below-market rate, a subsequent “commercial investor comes in at a higher market rate” with its loan.

Vermont State Rep. Michelle Kupersmith (D) sponsored the L3C bill in hopes that new L3Cs will spur work force development. “We have businesses saying they need workers and can’t find them, and [high school] grads saying they can’t access the skills needed to take advantage,” Kupersmith says. The main impediment, she says, is “a lack of capital.”

Why Create a New Mousetrap?

Some contend that there are already ways to provide money for this type of training. L3C proponents say that may be true, but that it isn’t being done very much.

This new structure, they say, will encourage more grant makers to take a chance on investments, by allaying fears of running afoul of the IRS. If the work is carried out by an L3C, the proponents argue, there won’t be any question that the IRS will approve PRIs related to it.

“When you set up an LLC [limited liability corporation] as an L3C, the law says it has to have socially beneficial service,” Lang says. “By making it an upfront proposition, we’re taking the position that there shouldn’t be a problem.”

Whether the IRS accepts that premise remains to be seen. Vermont can allow all the L3Cs it wants; if the IRS rejects PRIs invested in many of them, the structure wouldn’t have much more use to foundations than the status quo.

The Vermont bill was crafted in part by Marcus Owens, a Washington attorney who for 10 years ran the Exempt Organizations Division of the IRS, which examines foundation activity. “It would conceivably make life easier for the IRS,” Owens says of L3Cs.

“We’re optimistic” that the IRS will be receptive to the idea, says Steve Gunderson, CEO of the Council on Foundations, which supports the L3C approach.

Thus far, the IRS has been silent on the issue. IRS officials declined to comment for this story, and have made no comment to Vermont on L3Cs, according to the Vermont secretary of state’s corporations division.

Eleven L3C companies have been formed in Vermont since June, according to that office.

Contacts: Bob Lang (914) 248-8443, Robert.lang@l3cadvisers.org. Read more about L3Cs at http://www.americansforcommunitydevelopment.org.