|

|

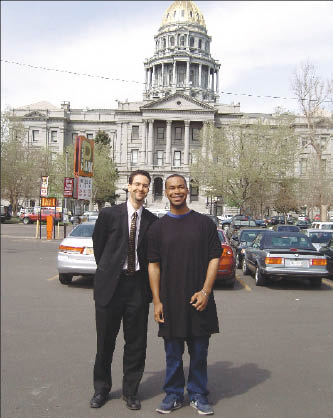

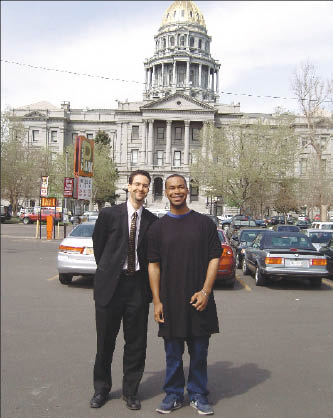

The Extra Mile: Foster youth Halston Green (right) is in the financial savings and education program at the Mile High United Way in Denver. Here, Green and Barclay Jones, vice president of the United Way chapter, prepare to meet with state legislators as part of this year’s “Take a Foster Youth to Work Day.”

Photo: Mile High United Way |

It’s not easy to teach teenagers to save money or to be savvy about financial matters. This can be especially true for low-income youth, whose families often have little history of savings and typically do not benefit much from such perks as tax-favored retirement accounts and home mortgage deductions.

A growing movement is working to address this challenge through programs that encourage low-income youth and their families to save money and build wealth. The young people in these programs typically get basic financial literacy training and varying degrees of financial assistance in saving money for long-term goals.

Perhaps the most prominent of these efforts is the Savings for Education, Entrepreneurship and Downpayment Initiative (SEED), which is under way at nonprofit organizations across the country. SEED youth get matched savings accounts; withdrawals are matched when the money is used for college expenses or another allowed purpose. Participants also are required or encouraged to attend classes on such topics as balancing checkbooks and managing credit card accounts.

Besides the obvious benefits to the families, the 10-year initiative aims to demonstrate that poor people can save, and to make the case for offering children’s savings accounts and financial education on a broad scale. Pending federal legislation would offer matched savings accounts for every newborn child.

Proponents say the results so far are promising. “Some qualitative data suggest that the youth are becoming more prudent and forward-thinking about how they spend their money,” said Professor Ed Scanlon of the University of Kansas School of Social Welfare. “Kids spoke a lot about impulse buying and distinguishing between wants and needs.”

The program also helps people develop saving as a habit so they build up assets over the long term, said Reid Cramer, research director of the asset-building program at the New America Foundation in Washington.

The initiative, which began in 2003, is run by the Corporation for Enterprise Development (CFED) in Washington, the Center for Social Development at Washington University in St. Louis, the Initiative on Financial Security of the Aspen Institute, the New America Foundation and the University of Kansas School of Social Welfare. Funders include the Ford Foundation, Charles and Helen Schwab Foundation and Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative.

SEED accounts are versions of Individual Development Accounts, which have been offered for years through a variety of federal, state and nonprofit initiatives. Some of the nonprofits participating in SEED also offer IDAs for adults and youths outside of the program.

Most youths participating in SEED programs receive initial deposits of up to $1,000 in interest-bearing IDAs. The teens and their families add funds to these accounts from their own savings. The youths can earn money for the accounts by achieving so-called benchmark incentives, such as participating in community service or completing financial literacy training. Withdrawals are matched if they are used to pay for education or training, start a small business, buy a home or finance retirement. Funds also can be rolled over into Roth IRAs or 529 college savings plans.

SEED participants range in age from pre-school to 23. Five of the 12 SEED sites are still operating, but will shut down by the end of this year as the pilot draws to a close. The next five years of the SEED initiative will be spent analyzing data and writing reports. (At least two of the youth programs will continue under different sponsorship.)

At a recent conference at the Corporation for Enterprise Development, and in subsequent conversations, representatives of organizations offering youth savings accounts discussed some of the lessons they’ve learned:

• It may take persuading to get some families to participate. According to the corporation, some families were afraid of tying up scarce funds or worried about financial scams. Some figured that their children would not attend college or would get full scholarships based on financial need, meaning there was little reason for additional savings. Others worried that increasing their savings would lead to a reduction in government income support payments. Not surprisingly, advocates say that teenagers were more likely to stay engaged with ongoing encouragement from parents, teachers and mentors.

• To make asset-building goals seem less abstract, it is important to allow flexible and short-term uses for matched funds, such as transportation or and child-care that help participants attend class. On the other hand, savings are often slowed by teenagers using the money for such “essential” items as cell phones and prom outfits.

• There is no consensus about the best way to deliver financial training, although conference attendees agreed that the training must not be dry and must be tailored to the audience. Scanlon said that while SEED participants perceived that their financial knowledge had increased, “I was seldom able to get them to tell me what they learned. … It seemed more about creating motivation and a social connection.”

• Direct deposit is helpful in making sure the money teenagers earn lands in their savings accounts. Debit cards can be hard for participants to manage.

The following four programs, three of which are in SEED, use various approaches to offer matched savings accounts and financial education to different populations of teenagers.

Rose Gutfeld is a freelance reporter in Chevy Chase, Md. Her email address is rgutfeld – at – comcast.net.

Juma Ventures

San Francisco

(415) 371-0727

http://www.jumaventures.org

The Approach: Juma Ventures, which says it launched the nation’s first IDA for youth in 1999, operates an extensive youth savings and financial education program in addition to its involvement with SEED. The IDAs support Juma Ventures’ overall efforts to help disadvantaged youth move from high school to adulthood.

Participants in Juma Ventures’ SEED program get no initial deposits; their own savings are matched up to $3,000. The participants can earn $300 in benchmark incentives by graduating from high school, $25 by beginning a required online financial training class and $175 for completing it. The class, which uses the MoneySkills curriculum, consists of 36 modules, each of which takes about 20 minutes to complete.

The youth must attend at least two Savers’ Club workshops, which are held monthly and feature speakers on such topics as taxes and investment accounts.

Some savers also get jobs from Juma Ventures, which employs young people at its concession services at major sports stadiums in San Francisco, Oakland, San Diego and Washington.

“Participants in our program begin to think about investment, critically analyze banking products and begin to pay close attention to their budgets and how they spend their money,” said Maria Sison, asset services manager at Juma Ventures.

She said it is important for people running youth savings programs to know the participants well and to provide flexible support tailored to their needs. She also recommended recruiting youth who are stable, employed and motivated to acquire assets.

While its SEED program will shut down at the end of the year, as the time for the pilot project expires, Juma Ventures has launched a state-wide pilot program, called Gain Resources Opportunity and Wealth. It plans to offer matched savings accounts and financial literacy training to 160 young people across California. Those accounts, funded by Merrill Lynch, among others, will allow youth to earn a 2:1 match on as much as $1,000 of their own savings.

History and Organization: The organization’s SEED program began in 2004 and will run through 2008.

Youth Served: The SEED initiative includes 75 youths, ages 14 to 18. Participants in Juma Ventures’ other youth savings programs range in age from 14 to 24. For all of its saving programs, Juma says 600 participants have saved more than $500,000, not including matching funds.

Staff: Four Juma Ventures staff members work directly with the assets department, where SEED is housed.

Funding: The Corporation for Enterprise Development provides the matching funds and administrative costs for SEED. Juma Ventures’ assets department gets funding from Citibank, Merrill Lynch, the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, federal Assets for Independence Funds and the Levi Strauss Fund, among others.

Indicators of Success: SEED participants have invested $99,893 of their own money in their IDA accounts, an average of $1,331 per participant. Sison said Juma Ventures considers success to be a participant’s first use of matched funds for an allowable purpose. Most of the participants have graduated from high school, and all of their matched withdrawals so far have been for post-secondary education expenses.

Six of 81 original participants dropped out of the program, usually because they did not want to use their funds for allowable purposes or were experiencing financial hardship.

Mile High United Way

Denver, Colo.

(303) 561-2386

http://www.unitedwaydenver.org

|

|

It’s the law: Tony Corley watches as Colorado Gov. Bill Ritter signs a bill championed by Bridging the Gap, which facilitates visits with siblings for youths in foster care.

Photo: Mile High United Way |

The Approach: At Mile High United Way, the SEED program is part of a broader initiative called Bridging the Gap, which is designed to help foster youth become self-sufficient adults. Participants, ages 14 through 23, must have been in foster care for at least one day while age 14 or older.

The participants do not receive their initial deposits of $100 each until they have completed a 12-hour financial education course and opened a bank account. Each participant also receives an Opportunity Passport, which includes an IDA and a debit card. The IDA is matched on a 1:1 basis and can be used for education and training, home ownership and micro-enterprise – just as in other SEED programs – but here the money can also be used for deposits on rental units, health care, renter, health and auto insurance, auto purchase and licensing and investments in stocks.

Kippi Clausen, director of Bridging the Gap at Mile High United Way, said the organization encourages participants to purchase smaller items, such as glasses or a computer, before saving for bigger things.

She said the difficulty many young people have in managing credit and debit cards is a good reason to offer the debit cards through the program. “We thought it would be important to have a debit card and work with kids on how to use it wisely,” she said, adding that her organization’s 300 savers have a total of about $70 in overdrafts every six weeks.

Among other opportunities, participants can establish relationships with professionals in education, employment, housing and other fields through Bridging the Gap’s Door Openers program.

Participants can stay in the program for 10 years, qualifying for as much as $1,000 a year, or $10,000 total, in matching funds.

Bridging the Gap members can earn additional funds for their accounts by achieving benchmark incentives, such as participating in community service projects and attending a variety of civic and cultural events. At Java & Juice, for example, the young people discuss issues with community leaders. Participants also can earn benchmark incentive funds by reaching steps on individual life plans that they create using the Web-based Ansell Casey Life Skills Assessment and Harrison Assessment programs.

The financial education classes, which are free, were developed by Young Americans Bank and cover budgeting, savings, banking and credit. In addition, participants are offered “tune-ups,” where they get specific advice on such topics as how to shop for insurance and what to look for in a car. Clausen says a participant may be offered a “tune-up” after he or she runs into a problem with a specific issue.

History and Organization: The program began in May 2005 and has no end date as of now.

Youth Served: 300 youths, ages 14 to 23, are in the program now. All are or have been in foster care.

Staff: Bridging the Gap is run by Mile High United Way employees assigned to the project.

Funding: Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, the Corporation for Enterprise Development, Mile High United Way and private donors.

Indicators of Success: Through the end of March, participants had made 130 asset purchases. Of those, 49 were related to education, 39 to vehicles, 34 to housing, six to health and two to investments. Withdrawals totaled $94,241.08.

Four participants have turned 24 and moved out of the program.

A recent survey of a single year of the program showed that the number of Bridging the Gap youth who were not receiving public assistance rose to 79 percent from 72 percent, and youth who were out of school and employed full time for at least six months rose to 64 percent from 40 percent.

YMCA of Metro Detroit

Detroit, Mich.

(313) 309-1552

http://www.ymcadetroit.org

|

|

Review time: Imani Johnson, left, a participant in the YMCA’s Minority Achievers program, goes over materials with Program Director Jocelyn Boyd.

Photo: YMCA of Metro Detroit |

The Approach: The Detroit YMCA’s program, which is not part of the SEED initiative, matches the savings of its participants at a rate of 8:1. To join the YMCA Minority Achievers program, the youths must come from families with income below a cutoff that depends on family size and income. For a three-person family, for example, the income limit is $33,200.

The youth must attend seven consecutive weeks of financial literacy classes, participate in a college or career preparatory program at the YMCA, and deposit an average of $50 into their accounts each month at a sponsoring bank

Jocelyn Boyd, site director at the Y, said the program aims to “break the negative financial cycle” for urban youth by helping them develop a habit of savings and get access to higher education. To do so, she said, it is necessary to take a holistic approach: “Money is usually not the only or main problem, so these students and families need support in other areas,” including character building and networking, she said.

Youths are required to participate in at least one YMCA character, college, career or community service initiative. “This way, we see them regularly,” Boyd said. “They are able to participate in programs with positive students and adults, and they can experience the world around them through college tours, company tours, exchange programs and the like.”

The funds can be withdrawn when youths graduate from high school and show proof of enrollment in secondary education, and can be used only for classroom-related expenses, including tuition, computers, books, supplies and enrollment fees. There are exceptions for emergencies.

The YMCA’s standard financial education classes, which are free for these participants, cover topics such as credit, savings, budgets and investment strategies. The seven-week course, taught by a financial literacy contractor, was designed with help from YMCA staff. All participating students attend class together, at a designated site. A quarterly class for parents, added this year, aims to reinforce savings strategies and encourage asset building and continuing education.

History and Organization: The YMCA’s program began in March 2005 and is funded to continue through 2012.

Youth Served: The program has served 56 youths, ages 14 through 18.

Staff: Two YMCA youth workers run the IDA program.

Funding: A grant from The United Way for Southeastern Michigan provides program funding.

Indicators of Success: The 54 continuing participants have saved $28,500, not including matching funds, and the program has given out $108,000 in matching funds to graduates. Boyd said a measure of success will be how many of the high school graduates complete college. The first class of participants graduated from high school in 2006.

Two youths from the same family have dropped out. They had siblings in college, and their family was unable to continue making deposits for the high school students while managing the college costs.

Cherokee Nation

Tahlequah, Okla.

(918) 453-5532

http://www.cherokee.org

|

|

The first SEED graduate at Cherokee Nation, Dena Squyres, practices writing checks.

Photo: Cherokee Nation |

The Approach: The 75 American Indian youth participating in Cherokee Nation’s SEED program received initial deposits of $1,000, and the program matches up to $750 in savings contributed by the teenagers or their families. The teenagers can earn up to $250 in benchmark incentives by participating in a small business or fundraising event, being a peer group leader, taking entrepreneurship, home-ownership or college readiness classes, maintaining a 2.0 grade point average, increasing their ACT college entrance exam scores, or having their parent or guardian attend financial education classes, among other activities.

The youths can withdraw the matched funds only after they have 1) completed 12 hours of financial education classes, 2) graduated from high school or earned a GED and 3) continued their education in college or technical school.

The money can be used for post-secondary education, to start a micro-business or buy a home, or to overcome so-called education roadblocks, such as child care and housing. “The challenge in working with high-school-aged participants is making the program ‘real’ for them,” said Anna Knight, acting commerce group leader at Cherokee Nation. “Students and parents had to believe that the end goal was something attainable, and sometimes focusing on a goal four years out was difficult.”

To address this issue, she and other staff members began talking about how the youths would get to college classes and where they would live, rather than just focusing on the importance of education.

Knight said such ancillary costs are more important than tuition for many of the participants, who get scholarships or, in the case of foster children, are eligible for state assistance.

Participating youth must take monthly financial education classes, which are usually held on site. The agency provides transportation to those who need it. An online course was offered, but participants didn’t use it.

The classes, which are free, cover financial plans, budgets, investing, credit and debt, bank accounts, insurance and career choices. Parents and other family members are encouraged to attend the classes; some are held in the evening, with an adult curriculum.

“Personal contact with the entire family was the most effective means to increase savings deposits,” according to Knight, who said some parents have signed up for the organization’s adult Individual Development Account program.

History and Organization: The program began in October 2004 and will run through the end of this year.

Youth Served: Cherokee Nation enrolled 75 American Indian youth, ages 13 to 15, who participated during four years of high school. Of those, 26 were foster children.

Staff: Cherokee Nation’s existing IDA coordinator handled financial education, accounts and bank relations, while other staff members provided administrative support. Participants also got support from Indian Child Welfare case workers (the nation’s equivalent of the child welfare system) and a counselor at Sequoyah High School.

Funding: The Corporation for Enterprise Development covered the initial savings deposits, the matching dollars, benchmark incentive funds and some administrative costs. Cherokee Nation paid for most of the staffing.

Indicators of Success: As of April 30, participants had saved $56,264.81 and accumulated additional matching funds of $54,463.13. Some participants started companies – a fan gear business and a sports calendar business – to raise money for their accounts, and some parents have requested budget and credit counseling.

Most of the participants graduated from high school this year, thus becoming eligible to request funds from their accounts. The first three who did so sought funding for housing or transportation.

While no one has formally withdrawn from the program, three have dropped out of high school, and five have not responded to contact from Cherokee Nation. Those students have three years to complete the program requirements and claim their money.