“I always felt isolated and alone” in foster care, begins Shenandoah Chefalo in “Garbage Bag Suitcase.” “As soon as I understood that the suffering I felt as a child was being felt by millions of other children, I knew it was time to write this book.”

“I always felt isolated and alone” in foster care, begins Shenandoah Chefalo in “Garbage Bag Suitcase.” “As soon as I understood that the suffering I felt as a child was being felt by millions of other children, I knew it was time to write this book.”

But Chefalo’s loneliness began much earlier. Her earliest memories are of being 4 years old, waiting for the moment “when Bill Cosby’s ‘Picture Pages’ came on in the middle of Captain Kangaroo. Locked in her room watching television was where Shenandoah felt safest from her parents’ violence. It was comforting. It was peaceful. It was safe. “There was no escaping the random violence of my childhood,” Shenandoah writes. But in her room, it was possible to pretend to be safe.

Chefalo’s parents abused alcohol and drugs, and were often behind on the rent, but it was her father’s violence, she writes, that terrorized the family. One time, when Chefalo’s dad beat her mom bad enough to give her a black eye that needed stitches, “the police laughed it off and didn’t even visit to press charges.” Chefalo and her mom escaped in the middle of the night. Her father found them a few weeks later.

Chefalo’s father began to unleash his violence upon her, as well. “He grabbed my arm and threw me face down on the grown,” she writes. “My face smashed into the ground, leaving a gash on my forehead from bouncing off the sprinkler head.” Violence became the norm.

If Chefalo was afraid of her father’s violence, she “lived in a constant state of fear of her [mother’s] criticism.” Chefalo remembers coming out of her locked room to find her mother having sex with a stranger on the couch; when the man protested, her mother simply said: “’I wouldn’t worry about her. She’s a fucking idiot and useless.” Both of Shenandoah’s parents denied her food as a regular form of punishment.

When Chefalo’s mother left the state without her, she discovered that the man she has known as her father is not her biological father, but her step-father — a step-father who had moved on with new family who has no room for her. So, Chefalo spends a few weeks living illegally in her grandmother’s retirement community before being turning over to the state to enter foster care.

“The general population does not understand the impact that the foster care system has on a person,” writes Chefalo. For her, foster care was, simply a “nightmare.” Overcrowded, with several other foster siblings in a dilapidated hose with more abusive, neglectful adults as her foster parents, Chefalo was trapped in disillusionment and disappointment. Luckily, a teacher took notice and suggested she apply to Michigan State University, where her college tuition would be free. Chefalo was accepted, and her life changed.

“Less than 1% of foster care children receive a four-year degree,” and “out of the nearly 1.6 million people incarcerated in the various correctional institutions nationwide, 1.3 had been in the foster care system.” Many of these children, like Chefalo, faced abuse and neglect at the hands of their foster parents — and their attempts to seek help were not heard. “What I didn’t count on,” writes Chefalo of her days in foster care, “were the endless feelings of loneliness and despair that would never dissipate, haunting me for nearly two decades, even after I left the system.”

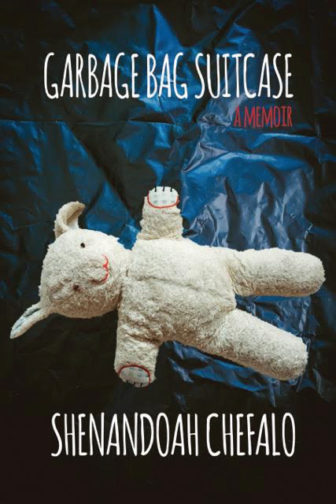

In “Garbage Bag Suitcase,” Chefalo pieces together painful aspects of her youth to provide a coherent picture of a neglected child who suffers further abuse in the foster care system. Against all odds, Chefalo is able to obtain an education, become a successful businesswoman, get married and have a daughter. This is a heartwarming, true story about the power of faith in oneself to rise above the hand life has dealt and triumph. In beautiful, lyrical writing, Chefalo gets to the heart of the story in words that are raw and meaningful, devoid of the trap of falling into easy sentimentality.

But “Garbage Bag Suitcase” is more than just Shenandoah’s story. The author offers powerful suggestions for how to revamp the foster care system. The solutions, grounded in Shenandoah’s firsthand experience, are practical and forthright. Although on a macro level they are geared toward those involved in legislation, Chefalo’s advice is also applicable to those working with foster care youth as case managers, therapists or other youth workers.Here, Chefalo includes a useful checklist for determining if one’s childhood experiences are adversely affecting one’s “physical, emotional and mental well-being.” She urges us to do this for two reasons: to better understand and heal from our own experiences and to better understand “why some people have reactions to situations that you might not otherwise understand.”

For Chefalo, the question is not “’What is wrong with that person?’” but “’What has happened to that person?’” Only then, she writes, can we “begin to change outcomes for those who have suffered great losses.”

Further Reading:

“Childhood Disrupted: How Your Biography Becomes Your Biology and How You Can Heal,” by Donna Jackson Nakazawa, Atria Books, 2015, 304 pages. A seminal text in understanding the link between childhood trauma and both adult behavior and adult biology, including higher risk of specific diseases.

“The Effects of Childhood Stress on Health Across the Lifespan,” by J.S. Middlebrooks, and Natalie Audage, Centers for Disease Control, 2008. A government-sponsored publication highlighting the severity of childhood stress and its link to diseases later in life.

“Healing Developmental Trauma: How Early Trauma Affects Self-regulation, Self-image, and the Capacity for Relationship, by Lawrence Heller, Ph.D., 2012, 320 pages. An exploration of specific therapies useful in healing childhood trauma in adulthood.