|

|

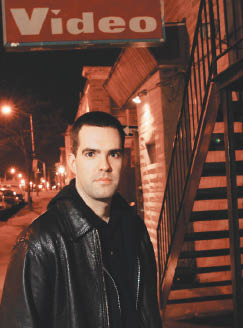

Rough start in Baltimore for Douglas Miller: “The neighbors and clients all thought I was a police officer, yet the police would follow me around, too.” Photo: Matt Spangler |

Baltimore—Barely a month into his career as a youth worker in some of this city’s more troubled neighborhoods, Douglas Miller was ready to quit.

“The hostility, the tenseness – I couldn’t handle it,” he says. “How could I counsel the kids? I just wanted to get into the car and go.”

It’s hardly an unheard-of reaction among fresh college graduates who launch their youth work careers dealing with troubled kids at programs like The Choice Program. The clients – mostly African-American boys who’ve been convicted of such moderate offenses as theft and drug possession – can seem as impenetrable as stone, and the environments – including the flashing blue lights of anti-crime surveillance cameras – can make rookies ask, “What am I doing here?”

While staff recruitment and retention is an issue throughout youth work, agencies that deal with juvenile justice, child welfare, substance abuse and homelessness face a particular challenge of burnout among young staffers.

“It seems like every day you find yourself in awkward situations,” says 24-year-old Destine Braxton, another caseworker at Choice. “It wears you down.”

“It’s one of the more crippling issues we struggle with,” says Melinda Giovengo, executive director of YouthCare, a 33-year-old Seattle agency that runs shelter, outreach and other services for homeless and runaway youth.

“We’re sending young people out to deal with some of America’s most vexing problems, and we’re paying them dirt. Is it any surprise that some end up overwhelmed by the stories they’re hearing from the youth – stories about child abuse, rape, drugs, juvenile prostitution or parental abandonment?”

|

|

Destine Braxton spends part of her day knocking on doors to keep in touch with youth in The Choice Program. Photo: Matt Spangler |

Although long hours, low pay and depressing conditions are part of the challenge, race and class often play a role as well, as suburban college grads try to connect with hardened urban kids.

The problem is severe enough to have spurred the creation in 1993 of the Hispanic Ministry Center, which later became the Urban Youth Workers Institute, based in Buena Park, Calif. Notes CEO Larry Acosta, “Idealism and passion only get you so far when you’re dealing with the realities of broken kids and broken families.”

That is why agencies like Choice have learned ways to help mitigate the risk of overwhelmed rookies.

Finding the Right Fit

Right away, Choice saw that it would have trouble finding people to take its front-line jobs.

Founded in Baltimore in 1987 by Mark Shriver, the son of Sargent and Eunice Kennedy Shriver, the nonprofit is now administered by the Shriver Center at the University of Maryland/ Baltimore County. Finding willing and capable caseworkers was always difficult, says Shriver, now vice president and managing director of U.S. programs for Save the Children.

The workers spend their days visiting convicted youths at their homes and schools – checking on their progress and well-being, listening to their concerns, connecting them with services and jobs.

“In the first interview, we told [job applicants] that it was a low-paying, highly demanding, tough job,” he says. “We told them, ‘You’re going to work with kids who are difficult’ ” – and about 80 percent [of the applicants] didn’t come back for a second interview.

“When we took the remainder out in the community and showed them what they’d be doing, we lost some more,” he says. “But those who were left were the ones who really wanted to do it.”

|

|

Davis: “Call them crazy, and they take it like a badge of honor.” Photo: Courtesy of The Choice Program |

Therein lie the first steps in preventing rookie burnout: being up-front about the rigors of the job and searching for people who appear ready for them. The Key Program – which employs some 400 caseworkers for its community-based and residential facilities across New England – looks for new college grads who plan to build careers in youth work, social work or teaching, because they have a sense of what they’re in for.

“We don’t paint a rosy picture when we’re recruiting,” says Carol Malone, the recruiting and training manager at Key, based in Framingham, Mass.

“But some are still not prepared,” she laments. “They just don’t understand what they’re getting into. For those who work out well, it has to be like a calling for them.”

Another strategy is looking for applicants with real-world experience. In southeastern Pennsylvania, the Community Service Foundation/Buxmont Academy recruits from college social work, teaching and psychology programs to staff its foster homes, schools, probation supervision and substance abuse services. But first, it gives many of them internships. Training Director Bob Costello says that because many of the agency’s nearly 100 counselors interned there while in college, they know the realities of the job.

If an agency can find someone who grew up in an environment similar to the communities they will serve, that’s a bonus. Consider LaTina Woolen, who grew up in Prince George’s County, a majority-black Washington suburb. A Family Studies graduate of the University of Maryland/College Park, Woolen now works in her home county as a Choice caseworker and appears quite comfortable. “I went to the same schools some of my clients go to,” she notes.

Getting Them Ready

As with similar programs around the country, the fundamental duty for the detached youth workers at Choice is to spend the day making the rounds of neighborhoods in the city – which last year produced the nation’s second-highest murder rate – climbing the porches and stairs of row houses and red brick public housing complexes, knocking on doors in an effort to talk with their clients. As with many such programs, the caseworker/client pairings can be odd matches.

Each year the Maryland Division of Juvenile Services refers 600 youths to Choice for community-based case management. Most are African-American boys; their average age is 15.

The 37 roving caseworkers are collectively more diverse than the youths. Most serve for a year through AmeriCorps, earning $21,000, a $3,000 stipend for health benefits, and $4,725 to put toward college loans or graduate school.

While some of them blend right in, many do not. Miller, a sociology graduate of the University of Maryland/Baltimore County, grew up in the upscale Washington suburb of Columbia, Md., and admits that working in largely African-American east Baltimore was hard to handle. “The neighbors and clients all thought I was a police officer,” he says. “Yet the police would follow me around, too.”

Megan Jupiter, a sociology graduate from the same university, was raised in Brick, N.J. – which, she noted this summer, was recently named “the safest city in America” in a survey by Morgan Quitno Press. In 2006, Quinto ranked Baltimore as the second-most dangerous city.

Jupiter was troubled by the lifestyles of her clients’ families, even in the largely white Anne Arundel County, Md., suburb where she worked. “It’s the lack of family structure,” she said. “It’s like as soon as [the kids] can go to the bathroom by themselves, they’re on their own.”

She quit after about four months. “She was uneasy going out on the job in the evening,” Choice Director LaMar Davis says. “It just wasn’t the right thing for her.”

This is why training is so vital. The 65 hours of orientation and classroom training for new Choice caseworkers includes resiliency, conflict resolution, navigating social service systems – and “the issues of poverty, class and race,” Davis says. “In particular, how you process what you’re dealing with, based on your own experiences, which may be quite different.”

Also covered, he says, are “crisis and safety issues.” Diagrams and photos of streets and alleys are used to discuss how to handle themselves in urban situations. At the Key Program in Massachusetts, the training includes how to deal with urban settings, covering such basics as finding well-lit spots to park where you can’t be blocked in.

Despite the concerns, Davis says no Choice caseworker has ever been victimized by street crime. “We’ve had caseworkers we’ve decided to move, because they were being threatened,” Davis says. “But the worst thing we’ve had in all our years was a caseworker who got bitten by a dog.”

“Of course,” he adds, “I also knock on wood every time I say this.”

But no amount of classroom training can teach youth workers how to really work with kids in harsh urban settings. As Acosta at the Urban Youth Workers Institute says, “You’ve got to know the rules of the street.”

That takes getting out there. Fortunately for rookies, the old trial-by-fire indoctrination has increasingly given way to gradual submersion. The rookies at Choice go out with other caseworkers for two weeks to meet their clients before heading out on their own. At CSF/Buxmont, Executive Director Craig Adamson says new workers are eased into the most stressful positions bit by bit, so they become comfortable.

“New employees used to say, ‘I’m worn out, I’m finished. I’m leaving,’ ” Adamson says. “But we don’t hear that anymore. … Our turnover rates are low now.”

Staff Support

The day begins for most Choice caseworkers with an 8:30 a.m. meeting at one of the 10 community-based offices in Baltimore or five nearby counties. First on the agenda: a client-by-client report on the previous night’s contacts and the upcoming day’s plans.

The basic unit of operation for Choice is a team of three workers for 30 youths, led by an office manager, who is usually a former caseworker. The caseworkers’ shifts usually end either at 5:30 p.m. or 11:30 p.m.

“It’s like 60 hours a week. You’re out going, going, going all day,” says Laura Shisler, a sociology graduate from the University of Maryland/College Park.

Caseworkers try to make face-to-face contact with each client at least once a day and keep tabs on their activities throughout. They visit schools, find structured out-of-school activities, get youths engaged in community service and help them find jobs, counseling and social services. They ask the boys if they met their probation officers as planned, or what they did at an after-school activity.

“I feel like I’m a mother for about 15 kids,” Shisler says.

While some youths and their parents treat the youth workers like allies or family, others see them as inspectors or cultural aliens. They answer questions in monosyllables. Parents sometimes shield their children from the visitors, saying, “He’s sleeping” or “He went to see his uncle.” The young workers occasionally find themselves shouting through mail slots to get someone in the home to respond.

At many programs, an important element of safety and staff support is having the workers call in by cell phone throughout the day, or work in groups. At Key, they are supposed to call every two hours. At YouthCare in Seattle, outreach workers connecting with homeless and runaway youth go out in teams of two or three.

While Choice workers stay out after nightfall, Key workers do not. “We used to be out all hours of the day and night, but we had to cut back on that,” says Malone, who began at Key in the 1980s. “These days, with gangs, guns and other issues, it’s a more difficult challenge.”

CSF/Buxmont officials say that retaining employees also depends on how they and the youth are treated. “They need to feel they have some say in what’s going on with their jobs,” says Costello, the director of training. That means providing opportunities for feedback and making adjustments.

“We recognize the [outreach] positions are entry-level, and they need a lot of mentoring, supervision and training,” says Giovengo at YouthCare. “Some workers are a little taken aback by what they see, and we give them a little more help.”

Job stress is why Choice won’t extend caseworkers’ jobs beyond a year, even for those who want to continue. “It’s far too intense, too hard,” Davis says. “We tried letting some stay on longer, but it turned out to be a rare person who could even last three or maybe six extra months.”

Malone says The Key Program limits caseworkers to “a year-and-a-half – that’s it.”

Rewards

One day last year, Douglas Miller turned in his resignation at Choice. Davis insisted that he first try working in a suburban area west of the city. There Miller found his niche.

Despite the tough grind, some caseworkers rave about the experience. Besides facing and learning about real-world problems, the young people develop the esprit de corps of front-line troops. “Call them crazy, and they take it like a badge of honor,” Davis says – apparently accurately, as several caseworkers note that they had been so described by friends.

Family and friends “laugh at me,” says Destine Braxton, the Choice caseworker, who has political science degrees from the University of New Orleans and Prairie View A&M University in Prairie View, Texas. “They say, ‘You have two degrees. Why are you hanging around with juvenile delinquents?’ ”

Many of the youths are fun to be around, hardly the image of delinquents. Some clearly have potential far beyond their brushes with the law.

And there are the rewards of seeing kids and families value the youth workers’ efforts. Braxton tells of one initially unresponsive 16-year-old who eventually seemed to worry about her: “He says, ‘Be careful out there,’ or says, ‘Thank you.’ It touches you a lot.”

Some of the staffers say the job has made them stronger. “After handling all this, I think I can do anything,” Shisler said on the eve of finishing her one-year assignment.

“I wouldn’t trade it for anything,” she says. “But I wouldn’t do it again.”