Gene J. Puskar / AP

The University of Pennsylvania.

After 19 months at the helm of the National Institute of Justice, Greg Ridgeway quit last summer to join the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania. Just days before he left, NIJ gave one of his new colleagues at Penn a $3 million grant.

Ridgeway, who recused himself from Penn’s funding request, assured Youth Today that the timing of the grant award and his Ivy League hiring was coincidental. While he’s now associated with the Penn Injury Science Center, Ridgeway said, he doesn’t even know its assistant director Douglas Wiebe, the lead investigator for the NIJ-funded project.

“I’ve actually never met Doug,” Ridgeway said.

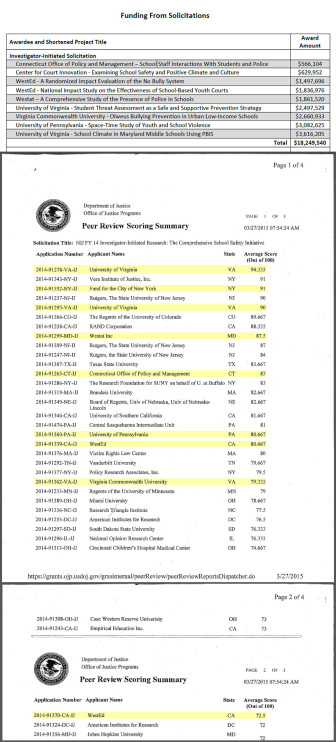

Nothing in the public record contradicts him. Until recently, though, that record was little more than an announcement that Penn was “among the highest-scoring, most relevant and rigorous” of 95 competitors for funding under NIJ’s Comprehensive School Safety Initiative.

Now, Youth Today has obtained confidential scores that show external peer reviewers ranked Penn’s grant application 18th, behind 11 higher-scoring funding requests that NIJ rejected. The summary shows three of the eight other grant-winners were ranked even lower: 19th, 23rd and 33rd.

NIJ, the scientific-research arm of the U.S. Justice Department, previously faced criticism that its records didn’t show how it chose grant recipients, so it opened up the process to let each applicant know why its request was approved or denied.

But the agency still withholds information that would let Congress, other applicants and the public judge whether the awards were fair.

NIJ relies on peer reviewers to assess the technical merits of research proposals but says their recommendations are advisory only. The agency makes few records of those decisions readily available, despite recent reforms aimed at greater transparency.

Peer review scores in particular are never made public, NIJ said in an emailed statement, since releasing them would not provide “full and fair context” to its decision-making and “could lead to misunderstandings that applications follow a strictly ordered ranking.”

But without access to those scores, congressional overseers and the public can’t tell whether grant winners are chosen fairly. “Without knowledge of the individual application scores, it is impossible to determine the appropriateness of award decisions,” Natalie Keegan, an analyst with the Congressional Research Service, testified in 2011 before a House subcommittee on procurement reform.

Youth Today’s review of scoring summaries and other documents supporting the 2014 grant awards raises new questions about how closely NIJ follows its own transparency guidelines.

Rutgers University, for instance, struck out in the 2014 funding cycle even though peer reviewers recommended all three of its funding requests, scoring each among the top 10. The Vera Institute of Justice in New York City got nothing even though peer reviewers ranked its proposal second overall.

The San Francisco-based nonprofit WestEd, on the other hand, won $3.3 million for proposals that peer reviewers ranked 19th and 33rd.

Given NIJ’s commitment to a rigorous science-based peer review process, why didn’t it simply fund the nine highest-scoring applications?

NIJ officials don’t want to talk about that, refusing Youth Today’s request for an on-the-record interview to shed light on those decisions. NIJ provided funding memoranda that summarized staff and peer reviewers’ recommendations but redacted numerical scores, which Youth Today obtained from another source.

Reforms to grant-making guidelines

The Justice Department overhauled policies at NIJ and its other grant-making branches after a 2008 Youth Today investigation found decisions on juvenile justice awards often ignored peer reviewers’ recommendations.

A department directive that year set the tone for the reforms that followed: “An otherwise uninformed reader should be able to understand the process used and the decisions made.”

NIJ had established new grant-making guidelines by the time Congress set aside $75 million for the Comprehensive School Safety Initiative to fund research and pilot programs for school safety. President Obama asked for the money after a gunman took 26 lives in 2012 at an elementary school in Sandy Hook, Conn.

Penn’s request proposed a sophisticated, four-year “space-time” survey of 200 school assault victims to determine “how, when, where, and with whom they spent time” beforehand and whether they could see their surroundings and potential attackers clearly. “Analyzing these data,” NIJ said, “will determine what individual and environmental factors could, if targeted, lead to the greatest reduction in school assaults.”

Despite its commitment to transparency, NIJ’s process for selecting Penn was not always clear:

- Peer reviewers could not agree whether Penn’s application should be funded, giving it a “mixed” recommendation, documents released by NIJ show. Those records give no clue as to what the reviewers’ reservations were, and NIJ has not yet responded to Youth Today’s April 30 request for their comments on the proposal.

- Names of the peer reviewers are not posted on NIJ’s website, as its revised transparency guidelines call for. Members of standing peer-review panels for most of NIJ’s other grant solicitations are named online, though, as are those used by other federal research agencies.

- Phyllis Newton, a subordinate of Ridgeway’s, approved Penn’s funding request in July 2014 without providing the written justification that is required when grant awards stray from peer reviewers’ recommendations. NIJ has not said why that justification was missing but, in an emailed statement, said officials saw the need for more details on grant decisions after Ridgeway’s departure. Newton provided that information in a November 2014 memo, shortly before she retired. Newton could not be reached for comment.

NIJ also overruled peer reviewers’ assessment of the technical merits of six recommended proposals that scored higher than Penn’s, internal documents show.

One application by Rutgers, for example, was criticized for the likelihood of contaminated data that would be difficult to interpret. The Vera Institute, with the highest-ranking proposal that wasn’t funded, was told its research measures were “underdeveloped.”

NIJ tells researchers and the public that the peer reviewers are responsible for evaluating the technical merits of grant applications. Grant awards are based on their recommendations, NIJ says, as well as other factors such as underserved populations, geographic diversity and past performance.

Spokesmen for Rutgers and the Vera Institute declined Youth Today’s request for comment.

Former NIJ and Justice Department officials, while not commenting specifically on the 2014 grants, say the agency is within its rights to revisit issues that peer review panels have already considered.

“Peer reviews are very important, but not the only factor that leads to an awarding of a grant,” said John H. Laub, NIJ’s director from 2010 to 2013 and now a professor at the University of Maryland. “In addition, peer reviewers can miss things.”

Observers also caution that scoring differentials of just a few points may have little meaning.

“Following scores slavishly is a bad idea. Reviewers are not perfect and often disagree,” said Akiva Liberman, a former grant monitor at both NIJ and the National Institute on Drug Abuse who’s now a senior fellow at the Urban Institute’s Justice Policy Center.

NIJ’s procedures criticized

Questions have swirled around NIJ, which doled out $233 million in grants last year, since outside agencies issued two scathing critiques of its funding decisions in 2009 and 2010.

A 2009 Inspector General’s audit found NIJ’s procedures did not guarantee fair competition for grants. NIJ staff helped review funding requests even though they had a conflict of interest, ordered grantees to use specific subcontractors without saying why and failed to document its rationale for choosing certain grant winners, the audit found.

A year later, the National Academy of Sciences issued a 320-page report that found poor record keeping and transparency made it hard to assess whether NIJ’s grant decisions were objective. Some 73 percent of outside researchers believed politics influenced those decisions, the academy reported.

“Insufficient transparency contributes to the opinions expressed by practitioners and researchers that NIJ decisions are not made on the basis of scientific criteria,” the NAS report found.

Alarmingly, the academy reported that NIJ couldn’t even locate at least one in four of the final reports on research it had commissioned.

Justice Department overseers had started to tighten up guidelines for its grant awards after embarrassing revelations in 2008 about grant-making at NIJ’s sister agency, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Top officials at OJJDP stepped down after Youth Today reported they had skirted grant procedures to select groups with ties to political figures, including former President George H.W. Bush and former Education Secretary William Bennett.

NIJ’s grant-review reforms included more stringent guidelines on handling potential conflicts of interest. By the time the agency solicited applications for the Comprehensive School Safety Initiative, Ridgeway had already filed paperwork that would recuse himself from any funding decision involving Penn, NIJ said.

The recusal left it to one of Ridgeway’s subordinates, rather than an independent third party, to make the decision on Penn.

NIJ defended that process as a simple matter of following its chain of command. “A direct report would be the person to whom responsibility would be delegated in the case of a conflict of interest recusal,” the agency said in an emailed statement.

Conflicts of interest, Ridgeway said, are inevitable as academics in the relatively small world of criminology move in and out of government posts that oversee research.

“That’s going to happen, because these are the kinds of institutions that do the kind of work that NIJ is interested in funding,” he said.

NIJ also must weigh the public’s interest in transparency, Ridgeway said, against applicants’ right to protect their intellectual property. “We sometimes have proposal writers who don’t want their review comments released because it reveals their big idea,” he said.

The National Academy of Sciences in 2010 called for opening up peer review scores and comments so grant applicants can see them.

“Many researchers said they just didn’t know what the process was,” said Charles Wellford, a University of Maryland criminology professor who co-authored the academy’s 2010 report, “Strengthening the NIJ.”

“Today, and I know this from experience,” Wellford said, “you get a fairly detailed explanation of what the peer reviewers saw as problems in your proposal. I think that’s a huge step.”

Other researchers and the public don’t see those comments and no one outside NIJ sees any of the raw numerical scores. In 2010, NIJ told the National Academy of Sciences that it considered the scores “pre-decisional, for internal information only.”

This article also published on Philly.com.