More than 20,000 American children were placed in group homes unnecessarily and for longer periods than they should, at higher cost to taxpayers and often to the kids’ detriment, according to data from 2013, the latest available.

Those findings are at the heart of the Kids Count report released today by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Even though both research and federal law now emphasize keeping children who suffer from abuse or neglect with relatives or in foster homes, some states still put more than a quarter of those kids in group placement, the study found.

“A small number of kids have such complex needs that they will need specialized care in a residential setting,” said Rob Geen, the Casey Foundation’s policy reform director. “But that should be a small number. It should be used like an emergency room, as a short-term intervention to stabilize kids.”

The report recommends keeping children with their families whenever possible, with the help of services “that are designed to come to them.” Child welfare authorities should try to recruit and train more foster parents, courts should have to provide “substantial justification” for placements in settings like group homes and agencies should be keeping detailed data on both placements and outcomes to guide their decisions, the foundation urged.

Geen said there’s bipartisan support to move public policy in that direction. The Senate Finance Committee, which oversees foster care legislation, is holding a hearing on the issue today, and President Obama’s latest budget includes increased support for foster care and treatment.

“We feel like we’re at a tipping point,” he said. “We’ve got momentum. We know from research what the right thing to do is, and we’re aligning our resources and our policy with what we now know.”

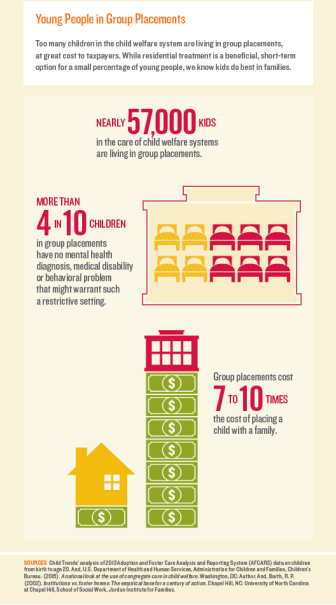

But of the more than 400,000 kids in the care of child welfare agencies in 2013, about 57,000 — roughly one in seven — were placed in group homes rather than in the care of relatives or foster families. And about 23,000 of those had “no documented clinical or behavioral need that might warrant placing a child outside a family,” according to the report.

Geen said that figure is likely to be “just the tip of the iceberg.”

“There are lots of other kids who have clinical needs who could be cared for in their own families or in another family setting,” he said. “I think if you apply the ‘my child’ test to these kids — what would we do if this child was ours? — just because a child has depression doesn’t mean you send a child off to an institution.”

Children in group homes are more likely to test lower than their peers in English and math, less likely to graduate from high school and more than twice as likely to be arrested as those placed in foster homes. In addition, young children in group placements are at high risk of attachment disorders, experts say. More than 11,000 of the group-home population was under 13, the report found.

“Those are particularly concerning, because child developmentalists will tell you the family setting is even more critical for young kids,” Geen said.

As if that’s not bad enough, Geen said the average group-home stay is far longer than most experts recommend. Most children see improvement in three to six months, after which the gains tail off or even reverse — but the average stay is now eight or nine months, at a cost to taxpayers that can run up to 10 times the cost of family placement.

“We’re keeping kids long past the time that’s long past any therapeutic value that’s being provided by the residential setting,” he said. “So we’ve got to prevent kids from coming in in the first place if they don’t need it, then using the residential setting for what it’s meant — to stabilize them so that they can perform and succeed in a family setting.”

The states with the lowest share of kids in group homes were Oregon, Kansas, Maine and Washington, where the numbers were 5 percent or less. In four states — West Virginia, Wyoming, Rhode Island and Colorado — the share of children and teenagers placed in group homes topped 25 percent. The highest was in Colorado, at 35 percent.

In part, Geen said, that’s because different states have adapted more quickly to the shift in policy that now emphasizes keeping youths in a family setting whenever possible. They’ve set up mechanisms to train and support relatives who can take in traumatized children or recruited more foster families; the states that haven’t done that are sending more kids to group homes “because that’s all that they’ve got,” he said.

“Until recently we thought that institutional care with nice buildings and rolling hills was actually good for kids,” Geen said. “What we know now from the research is that family is critical for a child to overcome the trauma they’ve experienced from abuse and neglect.”