Why use ineffective interventions with youth? Why not use interventions that work based on the resources a student has? Why not involve the youth in the development of his/her own resources for the long term?

Why use ineffective interventions with youth? Why not use interventions that work based on the resources a student has? Why not involve the youth in the development of his/her own resources for the long term?

I was doing work in a community in Texas. At break, one of the women in the audience came up to me and told me the following story:

She was a member of a Wednesday-morning prayer group. This group had a young lady who was in community college. The women really grew to care about her and found out that she came to the prayer group on the city bus. So the women pooled some money and bought her a used car.

Two weeks later, when she came to the prayer group, she was on the city bus. They asked her what happened to the car, and she told them she had sold it so she could buy her boyfriend a motorcycle. The women were furious.

I said to the woman: “That young lady knew two things about her environment that you did not. She knew she could not keep the car. She knew that she did not have the resources for the car (gas, insurance, tires, maintenance, etc.), and she knew that if anyone asked to borrow the car, she would have to say yes. She knew very few people would ask to borrow the motorcycle, and she thought that if she told you she did it for a relationship, you would be OK with it.”

Interventions only work if the resources necessary to do the intervention are available.

Resources include:

- Financial: Having the money to purchase goods and services.

- Emotional: Being able to choose and control emotional responses, particularly to negative situations, without engaging in self-destructive behavior. This is an internal resource and shows itself through stamina, perseverance and choices.

- Mental: Having the mental abilities and acquired skills (reading, writing, computing) to deal with daily life.

- Spiritual: Believing in divine purpose and guidance.

- Physical: Having physical health and mobility.

- Support systems: Having friends, family and backup resources available to access in times of need. These are external resources.

Other necessities are:

- Relationships/role models: Having frequent access to adult(s) who are appropriate, who are nurturing to the child and who do not engage in self-destructive behavior.

- Knowledge of hidden rules: Knowing the unspoken cues and habits of a group.

- Formal register: Having the vocabulary, language ability and negotiation skills necessary to succeed in school and/or work settings.

The key motivator to do anything is whether or not there is a strong relationship with an adult. Two questions — Who do you care the most about? Who cares the most about you? — tell you that answer. What you are listening for is an adult. If a youth does not give you an adult (if they name, e.g., “my 2-year-old brother,” “my dog,” etc.), then the youth is significantly at risk. The first intervention becomes to find an adult with whom they can develop a relationship of mutual respect.

When assessing resources, youths themselves are the best sources. Once a youth has trust in the adult, we give the youth this list of resources and tell them that these are resources that individuals have and use to solve problems. We ask if they are willing to tell us about their resources, and we go down the list. Once those resources are identified, they can begin to identify with the adult what might work. Specific checklists to analyze resources that youth can use can be found in my book “Under-Resourced Learners.”

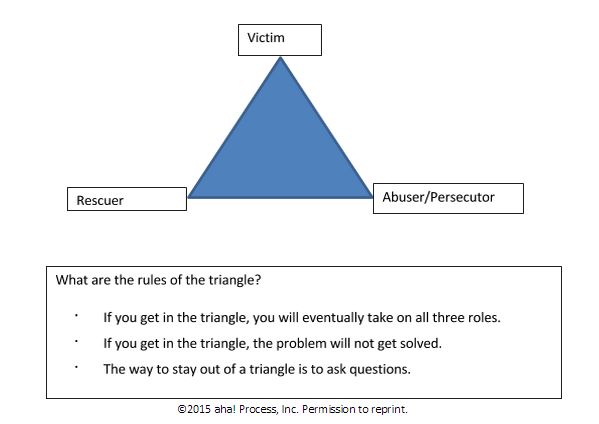

When resources are unequal or scarce, then individuals often get in a triangle that never solves the problem and continues the situation. This triangle is called the Karpman triangle (Karpman, 1968).

Sandy had a son whom she pushed relentlessly to do his homework and get the best grades.

Even when he was in high school, she went after school almost every day to his locker and got his assignments and homework (rescuer). Ray became valedictorian of his high school class. He got a scholarship to college.

But in college Ray had no idea how to take care of himself, and he flunked out at the end of the first semester. Sandy felt like she was a failure as a mother (victim). When her son flunked out of college, Sandy was furious with her son and told him so in no uncertain terms (abuser).

Ray got a girl pregnant and married her (victim). They stayed with Sandy (rescuer). Ray had an affair with another girl, divorced his first wife and had a child with the second girl. Sandy regularly rescued him. When she felt like a victim, she verbally abused him for it.

Ray in turn felt like the victim of his mother’s interference. He then abused his privileges in Sandy’s home and set up a situation so that he was “rescuing” another girl. The cycle continued.

For our youth, the awareness of their resources — both for them and for the adult — is critical to identifying the interventions that will actually help the youth. Staying out of the triangle will ensure that youths develop the “resource muscles” that allow them to begin to address issues in their own lives.

Ruby K. Payne, Ph.D., is the founder of aha! Process and an author, speaker, publisher and career educator. She is recognized internationally for “A Framework for Understanding Poverty,” her foundational book and workshop.