Each month, when I sit down to write my Remix Column, I scan the last month of Youth Today news stories. I was pleased when the story at the top of the page was Zen Dens, Peace Rooms, Chill-Out Spaces. Brian Rinker’s story carefully documents how schools and out-of-school time programs are creating staffed, voluntary sanctuaries where any student can decide to go to cool down or recalibrate before returning to class.

Grounded in the science of learning and development, these spaces normalize everyone’s occasional need for quiet reflection and even individual support. They are a far cry from the quiet rooms and detention rooms students were sent to for punishment. And they are timely, given the upticks in stress, anxiety, depression and other mental health concerns that predated but have certainly been exacerbated by COVID-related disruptions. Rinker shares numbers from the social and emotional learning director at the Boys and Girls Club of Greater Green Bay, in Wisconsin, who reports that the number of kids contemplating suicide jumped from one or two a month pre-pandemic to one or two a week.

Grounded in the science of learning and development, these spaces normalize everyone’s occasional need for quiet reflection and even individual support. They are a far cry from the quiet rooms and detention rooms students were sent to for punishment. And they are timely, given the upticks in stress, anxiety, depression and other mental health concerns that predated but have certainly been exacerbated by COVID-related disruptions. Rinker shares numbers from the social and emotional learning director at the Boys and Girls Club of Greater Green Bay, in Wisconsin, who reports that the number of kids contemplating suicide jumped from one or two a month pre-pandemic to one or two a week.

But my mood changed when I scanned the remainder of the list. Pandemic, culture wars revive ‘school choice’ policy push. S.C. committee advances limits to classroom teaching on race. Schools face pressure to take harder line on discipline. For foster youth, new restrictions make abortion access even more difficult. These are only four of at least a dozen stories focused on efforts to give parents, schools, agencies or legislators more control over what children and youth can learn and do. There may be more willingness to give them the freedom to calm their own bodies and behaviors. But, once calm, they go back to classrooms and health clinics where they have increasingly less freedom to explore real world dilemmas and make real life decisions.

This contradiction is driven by fear, not facts. Children are applauded for being individually self-aware. But teachers are threatened for helping them make collective meaning of this awareness beyond the moment. And those threats and fears are spreading from the classroom to the world of voluntary afterschool and community-based youth programs.

Byron Sanders, president and CEO of Big Thought, a Dallas-based nonprofit that works with marginalized youth, recently sent me a link to a piece from the Dallas Express, a site published by Dallas-based hotel magnate Monty Bennett, who was featured in a 2020 New York Times story about what the Times called a fast-growing network of nearly 1,300 websites built on “propaganda ordered up by dozens of conservative think tanks, political operatives, corporate executives and public-relations professionals.”

The Dallas Express piece explicitly links social-emotional learning to critical race theory and claims that the Dallas school district is using taxpayer money to pay Big Thought for what the Dallas Express says are politically-biased afterschool and summer programs. The Dallas Express’ main complaint is that Big Thought’s educational philosophy “may stem, at least in part, from its assumption that ‘income, community resources, race and English proficiency largely determine opportunities for success,’ neglecting other factors like personal responsibility, good parenting, and having the drive to succeed.” That last part is notable — “neglecting other factors like personal responsibility, good parenting, and having the drive to succeed.”

This false dichotomy must be unpacked and exposed. When one reads Big Thought’s website thoroughly rather than picking and choosing quotes as the Dallas Express did, it becomes easy to see how Big Thought works, and what the organization truly aims to achieve. Collaborate with families. Engage with young people. Close the opportunity gap. Ensure all young people achieve greatness. Institutionalized racism is a part of U.S. history. Case in point, the year-long “Road to Healing” listening tour Interior Secretary Deb Haaland is conducting to hear directly from victims and survivors of abuse at government-backed boarding schools.

Courtesy of Edge Research and Learning Heroes

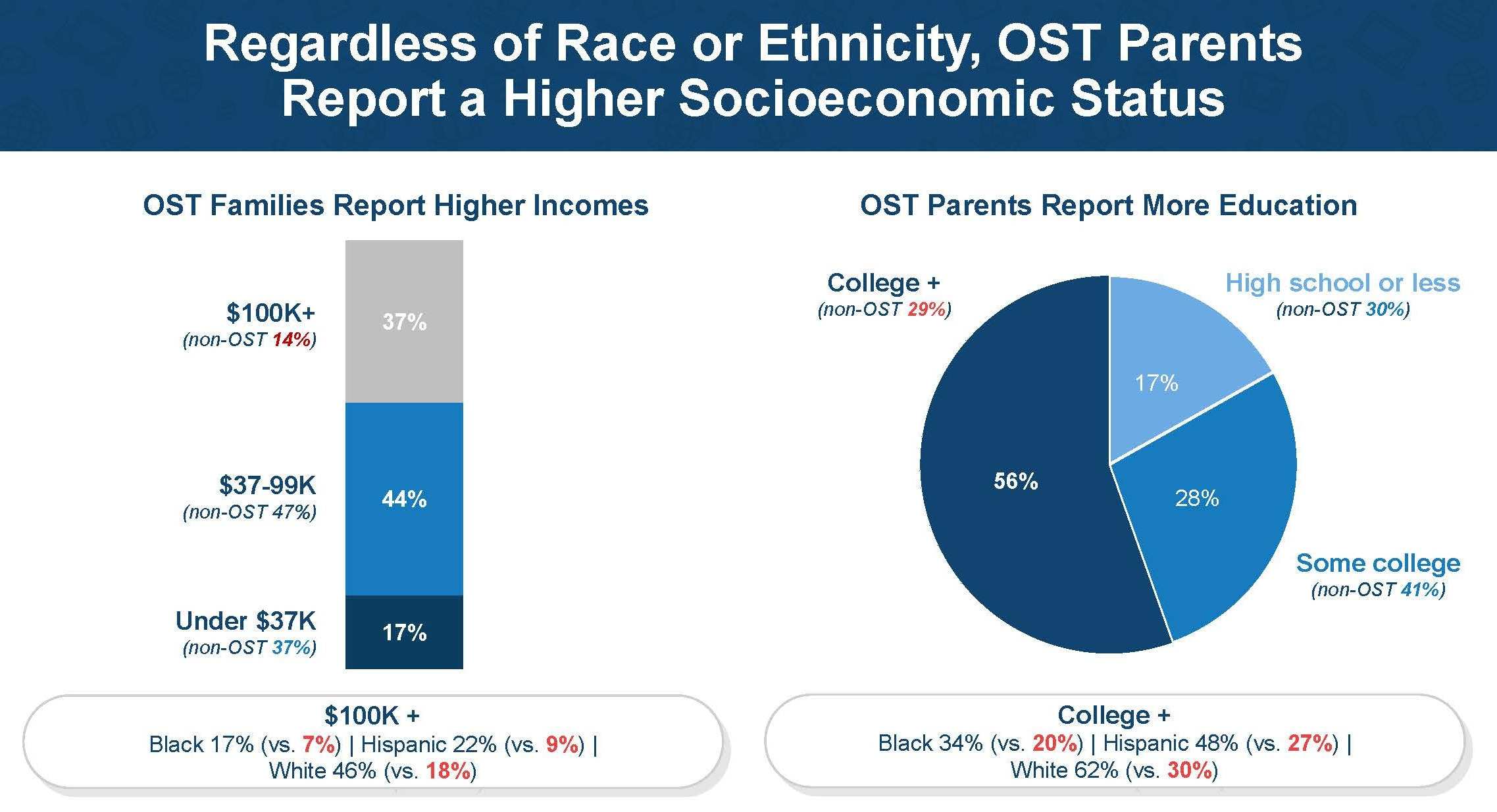

A 2021 national survey by Edge Research for Learning Heroes found clear differences in out-of-school time participation among families of different income and education levels.

Opportunity gaps are a fact. According to a recent study, affluent parents, in addition to having access to better-resourced schools, spend nine times as much money on supplemental learning supports than low-income parents. A 2021 Learning Heroes survey confirms that this is not a desire gap; this is an income/opportunity gap. Black, White, or Hispanic, parents with incomes over $100,000 were about 2.5 times more likely to have their children enrolled in out-of-school time programs than those with incomes under $37,000.

The vast majority of parents, regardless of race, income, or language proficiency, have similar goals for their children that include personal responsibility, persistence, and initiative. They also include empathy, compassion, respect, self-control, critical thinking and leadership. And parents have a keen sense of the natural division of labor for skill development between home, school and out-of-school time programs.

Intermediary organizations like Big Thought are needed to partner with schools, mayors, families and hundreds of nonprofit organizations and community educators to ensure that every young person not only has the right to take time to be calm when overwhelmed, but the right to find greatness through academics, through art, through service, and through collective exploration of differences.

Artivism, a Big Thought program for secondary students, encourages youth interested in the arts to use their talents to advance social justice issues. Getting young people to work in teams, to persevere, to curate projects for public scrutiny that give them an opportunity to lead discussions on topics that matter may lead to tough conversations. But that’s good youth development.

I understand the discomfort that arises when people see captions about social justice below photos of brown and black teens. But maybe the solution is to expand the discussions, not shut them down. Before we take more steps to narrow young people’s choices because of hyped-up conflations of acronyms and buzzwords, we must pause, find a peace room and look at what parents are telling us. Solidifying one’s identity, after all, is one of the primary tasks of adolescence. Three-quarters or more of parents across all racial, ethnic and income groups looking for out-of-school time programs want programs where their children can gain confidence, develop social and emotional skills, pursue their passions, and be exposed to new experiences. Out-of-school time programs give children and teens the support and freedom needed to develop agency and identify. If we politicize these core developmental milestones, none of us will be safe.

***

Karen Pittman is a partner at KP Catalysts and the founder and former CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment.