Ryan Sims was a recent college graduate when he started work two years ago at the Boys & Girls Clubs in Indianapolis.

It didn’t seem like a long-term job to him.

“I thought it would be a year or so and I would leave,” he said.

But something changed his mind — an organization called The Journey.

Heather Richard is an experienced manager in the field of youth work. She supervises a staff of 30 in five after-school programs at Blue River Services Inc. in southern Indiana.

After a three-day retreat that focused on self-renewal, she went back to Blue River Services and organized a paid retreat for her staff so they could relax and get to know each other outside of their usual workday. She wanted them to know that their work was appreciated.

She, too, was influenced by The Journey.

Begun in Indianapolis in 2002, The Journey is a nonprofit organization that supports the personal and professional renewal and development of youth workers.

The need is great: Youth workers often face low pay and high stress in their work. High turnover and burnout can be problems in the field.

Each year The Journey accepts a group of fellows in Indiana who, in a series of retreats, explore their own mission, connect with a community of other youth workers and expand their ideas of what they can accomplish on behalf of young people.

The Journey “helps people show up whole,” said Janet Wakefield, the organization’s chief exploration officer.

About 1,000 fellows — ranging from students to leaders of organizations — have gone through the program since its beginning, she said.

Connecting to what’s important

Through The Journey, fellows get clear on what they are passionate about, and they listen to their heart, Wakefield said.

The process “goes deep really quick,” she said. Journey fellows feel very connected to each other by the second retreat, she said.

For example, Sims said that initially he only knew one other person in his group of new professional fellows.

“We got to know each other quickly,” he said. “I felt this really great bond.”

In the process of Journey retreats, fellows get rid of busyness, fear and the judgment of themselves and others, Wakefield said. They focus on what they need to do to be their best self, she said.

“It was a safe space but unpressured,” said one participant who took part in 2003 and was quoted in an evaluation report, “Connecting and Inspiring Youth Work Professionals: An Evaluation of the Executive Journey Fellowship 2003-2011.”

So often “you don’t bring your true, authentic self [to your work],” Wakefield said. People are afraid of not being good enough, but they really should be afraid of being so good but not doing what they are capable of, she said.

It’s about being authentically who you are with all the bumps, she said. “It’s really the way we want wholeness where we work and live.”

Funded by the Lilly Endowment, The Journey “started with the idea of supporting people who provide support to young people,” Wakefield said.

The way to have the highest-quality services for young people in Indiana is to have the highest-quality youth worker, she said.

The foundation already had programs supporting Indiana teachers and clergy. The Journey extended the support to youth workers.

While there are other organizations focusing on the training and professional development of youth workers, “very few organizations start with inner work,” Wakefield said.

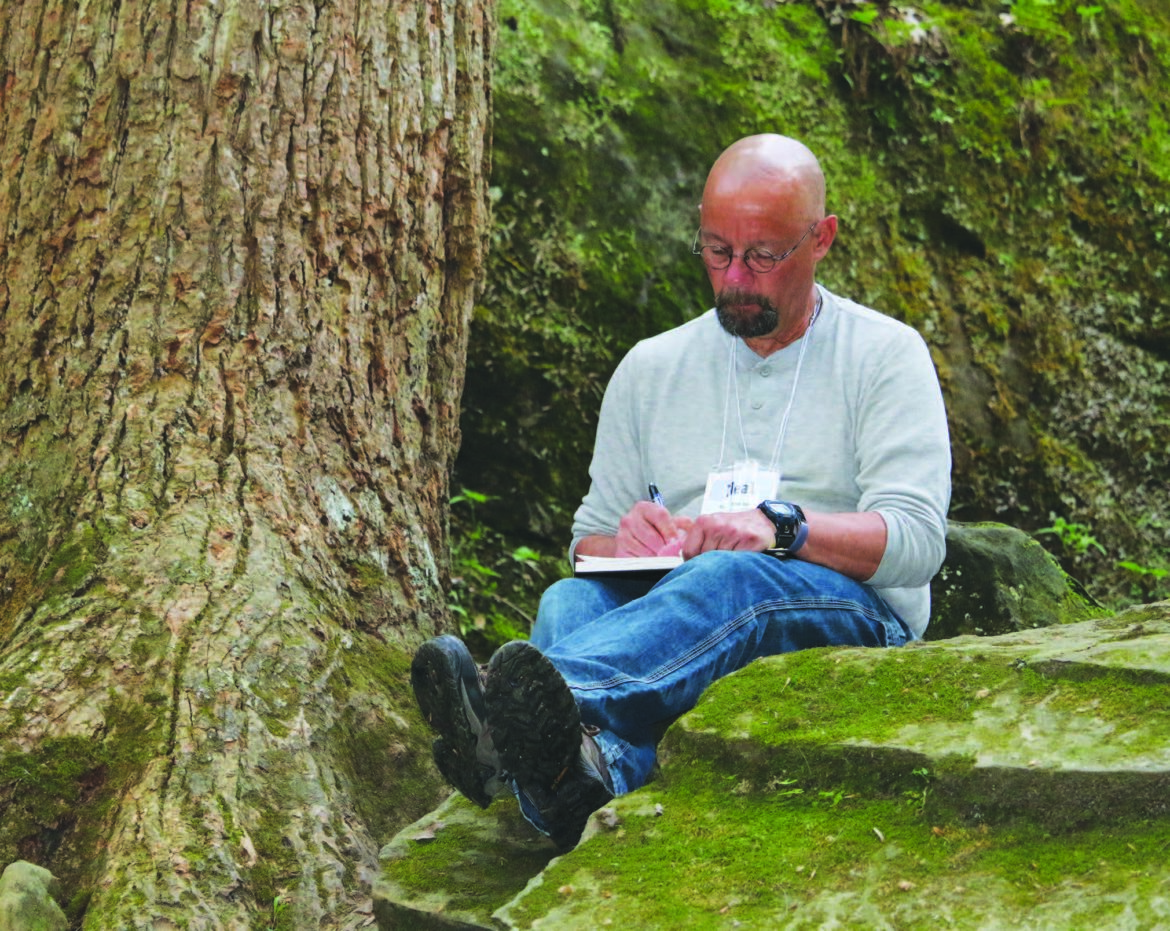

Neal Morehead, a 2017 executive fellow at The Journey, does journaling during a retreat. Morehead is program director at Camp Tecumseh YMCA in Brookston, Indiana.

Journey fellows “begin to lead differently and care differently,” Wakefield said.

Who takes part?

Each year, The Journey welcomes 25 to 30 fellows in each of three groups:

- executives in youth-serving organizations,

- new professionals in the field of youth development and

- college students considering a career in youth work.

Many participants are nominated by fellows from previous years.

The executive group, defined as those who have influence over the lives of youth workers, come together in four all-expense-paid three-day retreats. Each also gets $500 to take back to their organization.

If they experience taking care of themselves and helping others, they can pay it forward to their staff, Wakefield said.

The new professionals group is made up of full-time youth workers who have one to four years’ experience in the field. They get grounded, connect with each other and learn how they can develop and grow in their field, Wakefield said.

They learn about credentialing programs and youth work competencies, she said.

They also learn they can make a living in this field, she said. “We help them find their tribe.”

Front-line staff can easily “burn out and flake away,” Wakefield said. They work long hours and get little recognition and relatively low pay.

“They stumble in and stumble out [of the work],” she said. “We thought it was important to pick this group up.”

Student fellows are sophomores or juniors in college who want to work with young people. They are often in social work or human services programs in college, Wakefield said.

As part of their fellowship, they investigate youth-serving organizations and apply for summer internships funded through The Journey.

Getting grounded

Each group has retreat activities that serve as a grounding, Wakefield said.

Participants tell stories from the land of youth work, for example. “The whole point is to get people refocused on who they are,” she said.

Fellows who are students write a mission statement called “My True North.” They explore what they would like to do, whether it’s working with pregnant teens, helping kids get into college or serving as a youth minister.

They consider internships in various organizations by comparing the organizations’ missions to their own mission statement.

Executives write a renewal plan.

“We discussed ways to maintain self-care so as to be more helpful to your staff,” Richard said.

“Self-care is necessary to be successful.”

New professionals are exposed to the Child & Youth Care Certification, and they determine the areas in which they want to grow. They visit each other’s organizations. They see other work environments, and they learn about salaries and benefits.

The Journey even provides a $20 stipend for each fellow to take another one out to dinner.

“There’s always this kind of connecting,” Wakefield said.

At their second retreat, new professionals take a close look at a particular system for youth, such as the juvenile justice system. They sit in a courtroom and talk to intake officers,” Wakefield said. “They spend time with adults who run residential or detention programs.”

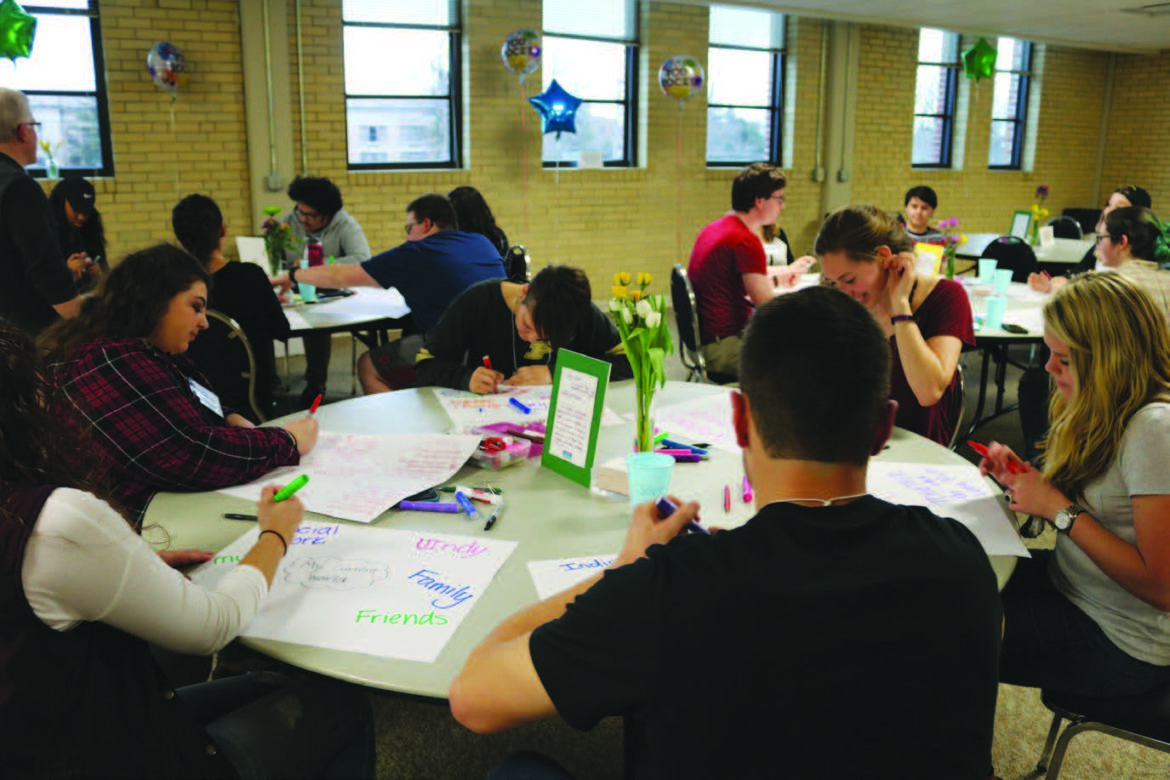

Fellows in The Journey’s 2017 student program work on a retreat activity designed to help them get to know one another.

They gain insight into how they can serve kids better so they don’t end up in the system.

At the third retreat, new professionals meet with executive fellows.

The process used by The Journey owes a debt to the Center for Courage and Renewal, an educational nonprofit that began as an experiment in supporting schoolteachers.

One of its founders was Parker Palmer, an author, educator and activist who focuses on self-renewal, trustworthy relationships and acting with courage on one’s true calling. His latest book is “Healing the Heart of Democracy: The Courage to Create a Politics Worthy of the Human Spirit.”

A broad view

The Journey envisions youth work in a broad sense.

“Youth workers are really anybody who helps young people grow up to be motivated, productive, self-aware people,” Wakefield said.

But youth workers often get “siloed,” she said. The Journey helps reconnect people who are working with youth in many different agencies and organizations.

Fellows have included foundation directors, judges, college professors, probation officers, youth ministers and librarians.

“It’s all about growing the field of youth development,” Wakefield said.

In her second retreat at Turkey Run State Park in Parke County, Indiana, last April, Heather Richard’s group went canoeing. Richard had never been in a canoe before. The activity was set up to reinforce communication and trust, “skills we need to use on a daily basis,” Richard said.

Creating trust is important, she said, so when she’s asking her staff to do things, they trust she’s asking purposefully.

“The Journey uses real-world experiences to solidify that,” she said.

Sims said he learned more about self-nurture. He does yoga now and is more tuned in to seeing stressors when they arise.

“[At The Journey] they encouraged us to write about our lives,” he said. It’s a way to process what is going on, he said.

His group of new professionals was also encouraged to reach out to other, he said. “We’re using each others’ skills,” he said.

He has a wider sense of what youth work is and the possibilities for him in the profession.

“The Journey has given me this whole new perspective,” he said.

How well does The Journey work?

The impact of The Journey on its executive fellows from 2003 to 2011 was evaluated by Nikki Hale Consulting, a field consultant with the David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality.

Evaluators analysed pre- and post-program surveys of executive fellows, observed Journey retreats and conducted individual interviews with fellows.

Journey fellows who were surveyed said they developed “trusting and sustained relationships” through the program, according to the report. They said retreat activities led them to reconnect with their passion for their work and alter their workplace practices in response. They developed a wider sense of purpose, the report said. The Journey had a 93 percent retention rate of these busy professionals during the course of a year, according to the evaluation report.

“All of the respondents here report an enhanced sense of the youth work field and a broadened perspective of the commonalities between all those working with young people within a youth work frame of reference,” according to the report.

The post-program surveys show that fellows had a significant increase in the belief that self-renewal is important and undertook activities that aid self-renewal.

Source: “Grounding, Connecting and Inspiring Youth Work Professionals: An Evaluation of the Executive Journey Fellowship 2003-2011,” by Nikki Hale and Michael Heathfield