WASHINGTON — A comprehensive survey of 33,000 students in 24 states released last week provides a bleak look at life for community college students who battle hunger and the specter of homelessness to pursue degrees that could change their lives.

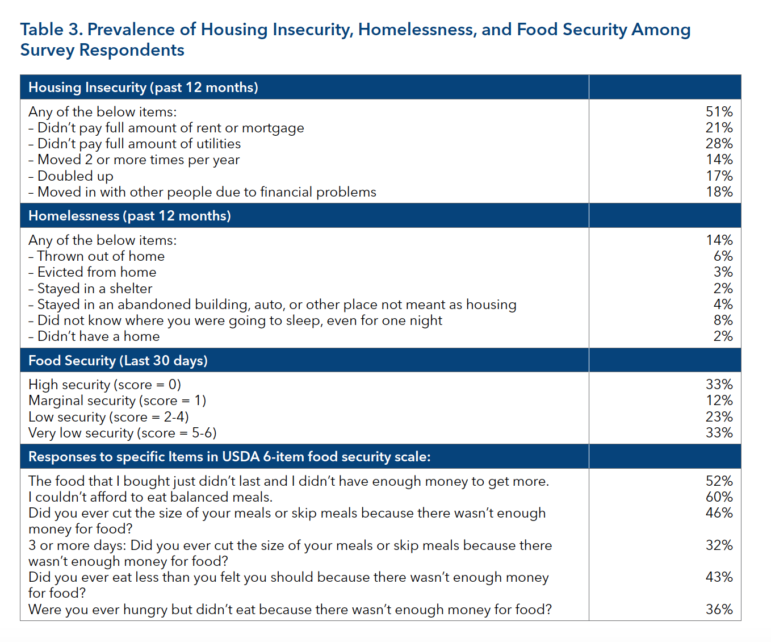

The study’s authors from Wisconsin Hope Lab, a nonprofit research laboratory dedicated to “improving equitable outcomes in postsecondary education,” found that one in seven community college students are homeless, and two-thirds are food-insecure. The challenge is particularly difficult for former foster children enrolled in college, with nearly 30 percent reported to be homeless.

Hope Lab worked with the Association of Community College Trustees to pull together what it called one of the largest sampling of community college students on issues of basic needs. Researchers also looked at difficulties facing young parents enrolled in school, and at whether they receive any form of financial assistance.

“While pursuing degrees despite enduring basic needs insecurity, community college students are nonetheless striving to ameliorate conditions of material hardship. Between 31 and 32 percent of students experiencing food or housing insecurity were both working and receiving financial aid,” the report said. “But in many cases, these efforts were not matched by other forms of support. For example, we estimate that 63 percent of parenting students were food insecure and almost 14 percent were homeless, but only about five percent received any child care assistance.”

Obstacles for college students experiencing homelessness are particularly difficult, the report found: “They were more likely than housing-secure students to work long hours at low-wage, low-quality jobs, and to get less sleep.”

These students face long odds against graduating, the report noted, although it did not cite specific graduation rates.

Even though many will not graduate, about one-third of homeless students receive some student loans, placing them in potentially crippling debt that will exacerbate their difficulties if they enter the workforce without a degree, the study said.

Innovations around nation sought

Jed Richardson, Hope Lab’s acting director, said the survey and research should be considered as a first step toward the larger goal of helping more homeless and housing-insecure students graduate.

“The first step is letting people know this is happening, because so many still think of the old way where you graduate high school, parents help pay for some college and you graduate in four years,” Richardson said. “That’s not the reality for many of today’s students. They are older, paying for school on their own and having to juggle rent, part-time jobs and expenses. Some also have families of their own to support.

“Of course, the big step is helping these students who are struggling get to graduations. And so what we are doing is looking at innovations that are happening around the country, and to see which can be scaled to other universities,” Richardson said. “So we want to identify what the students need, and then focus on what works and doesn’t work. It’s a long process.”

[Related: Federal PSA Campaign and Study Aim to Increase Awareness of Youth Homelessness]

Colleges and universities across the country are often not equipped to handle the specialized needs of homeless or housing-insecure students, several speakers and researchers said last week at the National Network For Youth’s annual conference in Washington. Universities don’t provide basics such as keeping dorm rooms open during breaks, or having a central location or person students in need can turn to, homeless advocates said.

Hope Lab found the same to be true at community colleges.

“Very few institutions have residence halls or employ designated caseworkers with the skills required to support this population,” the report said. “It can be difficult for practitioners to know much about the experiences and needs of this very vulnerable group of undergraduates.”

Trained staff, targeted aid needed

Most of the respondents struggled not only with housing, but also reported that they often had trouble affording food.

“Even so, less than half received any type of food-related public assistance, and just 18 percent got any support from housing-related public assistance. They were more likely than housing-secure students to receive the federal Pell Grant (50 percent vs 35 percent) but not much more likely to receive state or institutional support.”

Homeless students in the study tended to be older than their housing-secure classmates, with 45 percent being over 25 years old.

Nearly 70 percent of students who responded were female, while the national average of female students in higher education is about 57 percent.

The study provides recommendations to community colleges, state and federal policymakers and to future researchers who look at the problem.

One called for colleges to hire case managers or train current staff members to “serve as a single point of contact for basic needs insecure students, and in particular homeless students.”

That plan was also embraced by advocates for homeless students during the National Network for Youth’s conference. Participants and speakers overwhelmingly said universities with trained staff make homeless students feel more comfortable, and can help them access the many grants and scholarships available to students in their situations.

The study also called on community colleges to address the food needs of their students, including having food pantries and community gardening programs.

The study recommends that advocates push their local and federal lawmakers to spend more on targeted aid programs for the most needy students, and to “reinstitute year-round Pell so students have access to summer support to make progress in their studies and to contribute to living expenses.”

“This is a pretty big problem and it’s not going to be solved overnight,” Richardson said. “This survey is a call to get more people involved from the innovation side, from the research side and from the education side.

“I am a researcher at heart, so I always want to see more data about what works and what doesn’t. We’re doing everything we can to put in place evaluations of various interventions around the country, and then share that with people in the field. This is just an early step.”