The Annie E. Casey Foundation

.

The lives of children improved by some measures during recent years, but their opportunities still are constrained by persistent family and neighborhood poverty, says the 2016 Kids Count Data Book.

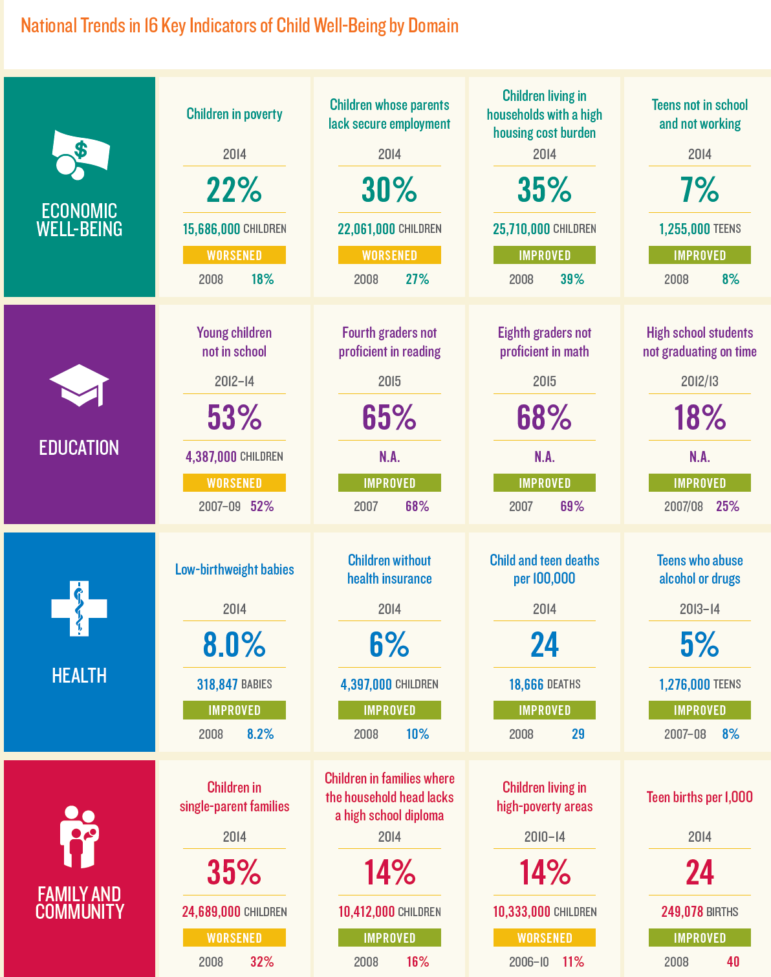

The annual report by The Annie E. Casey Foundation looks at measures of child well-being at the state and national level in four categories. Broadly, this year’s findings show gains in education and health — but some setbacks in measures of economic well-being and family and community, according to the report.

In recent years, birth rates among teens fell 40 percent, the percentage of children without health insurance dropped from 10 percent to 6 percent, and test scores and graduation rates improved, findings that are promising for the future of children who grew up during the recession and in its wake, according to the report.

But the percentage of children living in poverty remained at 22 percent in 2014, up from 18 percent in 2008 and unchanged since 2013. And the number of children living in high poverty grew from 11 percent from 2006-2010 to 14 percent in 2010-2014, according to the report.

The findings point to a need for lawmakers to pay close attention to the needs of children and families — and to make clear their plans for policy improvements, said Patrick McCarthy, president and CEO of the foundation, in a news release.

[Related: Time to End State-sanctioned Assaults on Our Schoolchildren]

“This generation of teenagers and young adults are coming of age in in the wake of the worst economic climate in nearly 80 years, and yet they are achieving key milestones that are critical for future success,” McCarthy said in the release. “With more young people making smarter decisions, we must fulfill our part of the bargain, by providing them with the educational and economic opportunity that youth deserve.”

He called on state and national candidates to release in-depth proposals to help children reach their potential.

Opportunity gap

The report also highlighted the “opportunity gap” between children in low-income families whose parents lack a college education and children in wealthier families with more education.

Highly educated parents have more money and time to invest in their children, an advantage that accrues as children age. The report stressed that children can and do succeed despite their family backgrounds, but their path is more difficult.

“The point is that declining economic opportunities and the intense stress that economic hardship places on families have stacked the odds against children growing up in low- to moderate-income households. They have fewer opportunities for moving up than the previous two generations,” said the report.

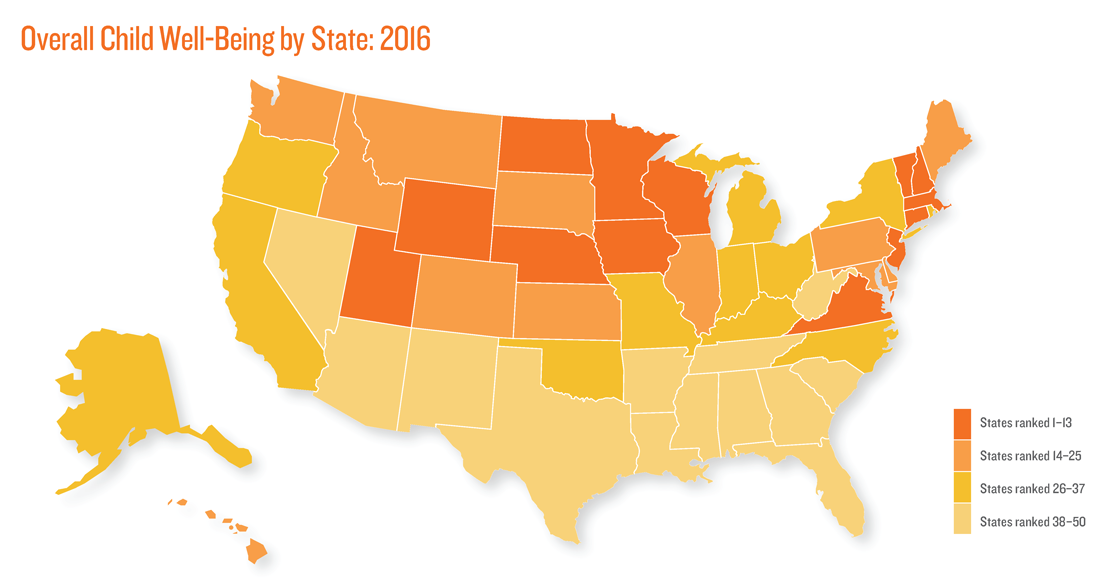

The report also breaks down its findings by state. For the second year, Minnesota was ranked first while Mississippi ranked last. States in New England filled out half of the top 10, while Midwest and Mountain states rank in the middle and the lowest-ranked states are clustered in the Southeast, Southwest and Appalachia.

The report also looked at the persistent racial and ethnic disparities experienced by African-American, American Indian and Latino children, who fared worse on many measures of well-being compared with the national average. For example, African-American children were more likely than average to live in high poverty neighborhoods, while Latino children are the most likely to live in household headed by someone without a high school diploma.

“By the end of the decade, children of color will be the majority of all children in the United States,” said Laura Speer, associate director for policy reform and advocacy, in a news release. “Our shared future depends on today’s young people fulfilling their potential.”

The report called for policy changes that promote opportunity, responsibility and security. The specific proposals include:

– expanding access to early childhood education and higher education and training;

– increased the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income workers without dependent children; and

– providing paid family leave.

More related articles:

Considering a Research-Informed Theoretical Framework for Trauma-Informed Approaches

Keeping Adolescents Engaged: What Can After-School Programs Do?