When I first started out in the poverty and self-sufficiency field almost 30 years ago, I helped facilitate a focus group in Philadelphia at a transitional work/homeless women’s shelter. Today, one woman still stands out.

When I first started out in the poverty and self-sufficiency field almost 30 years ago, I helped facilitate a focus group in Philadelphia at a transitional work/homeless women’s shelter. Today, one woman still stands out.

She had several children, but each had been removed from her care and her parental rights terminated. Although she was only in her 30s, she looked much older. During the focus group, she shared how she had finally turned a corner — was working and ready to find her own place. I asked her what helped, after so many years of hardship and loss, and her response surprised me: dental work.

She shared her long history of domestic violence, having had her front teeth knocked out as a teen and never being able to get them fixed. “I couldn’t get a job,” she said, “because I couldn’t smile.”

When working with young people in a range of human service and court systems, it’s not uncommon to have a client who has experienced trauma. In the rush of case management work, unearthing these experiences, especially with older clients, can be difficult, as can assessing the effect they have on their development and ability to fully participate in services.

Emerging research on childhood and adolescent brain development suggests that traumatic and adverse experiences among children and youth can cause harm far into adulthood. This research finds that adversities, when chronic and unbuffered, can affect an individual’s executive functioning capacities, such as those relating to working memory, self-regulation and organization, and ultimately affect one’s socio-economic status and workplace success.

[Related: Teen Stress and the Growing Brain]

Translating these findings into direct service practice is uneven across social-service sectors. Behavioral and mental health, and substance abuse providers are incorporating trauma-sensitive and informed processes. Trauma-informed self-sufficiency programs (such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, workforce and reentry), however, are in their infancy in applying these insights and assessing how, where and when to address trauma among their clients.

All long-term social welfare practitioners have seen the pendulum swing in many human service systems — from coordination to isolation and back, from individual foci to families to multigenerational approaches. What we know today about how we think, engage each other, learn, overcome adversity and sustain motivation has grown substantially. The infusion of trauma-informed care approaches across sectors acknowledges this growing understanding and is timely in the face of alarming statistics on the level of violence and trauma exposure children and families experience.

Drawing from rich literature bases on learning theory, behavioral health trauma-informed frameworks and our understanding of executive functioning skills, new frameworks must be considered as human service sectors embark on trauma-informed culture shifts.

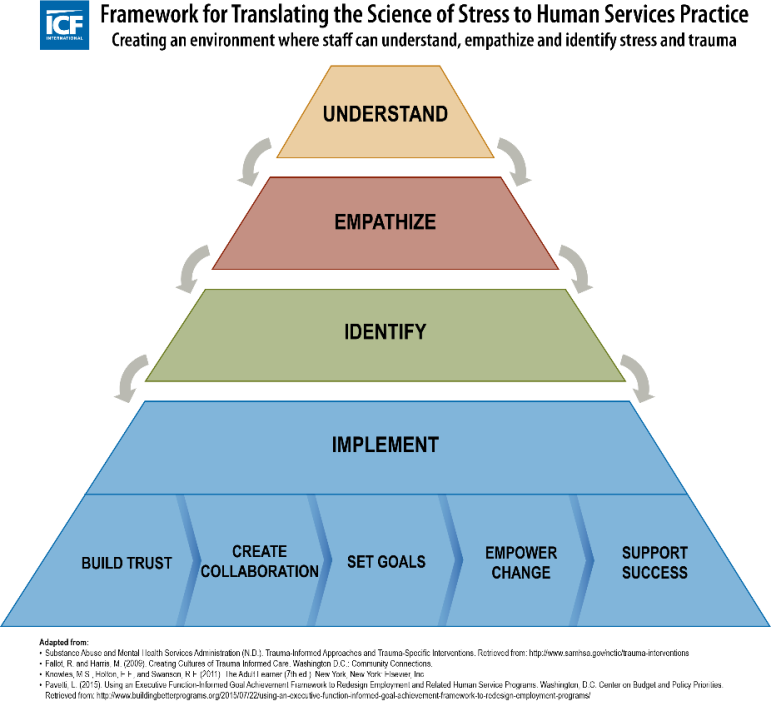

The theoretical framework in Figure 1 begins to link existing work in trauma-informed care with new brain science and the on-the-ground realities of youth- and young adult-serving programs. This framework offers a multitiered organizational change approach, which aims to improve staff understanding, build individual and organizational capacity, identify adversity and implement real practice, policy and case management changes.

It is meant to be actionable and adaptable for direct-service providers primarily working with older youth and young adults in self-sufficiency, workforce and reentry fields. For each stage, it supports organizational shifts that align with current trauma-informed approaches but also infuses additional learnings with older youth and young adults in mind:

- Understand: Disseminate knowledge and information about childhood and adolescent stress and trauma and its effects on child, adolescent and adult executive and other functioning.

- Empathize: Support the diffusion of this new learning by promoting opportunities for staff to build community, empathize with each other and with clients.

- Identify: Measure current activities against best practices and adopt standardized, structured assessments, appraisals or evaluation tools to identify client stressors, barriers, traumas and/or executive skills deficits.

- Implement: Implement new practices and policies that offer individualized and comprehensive case management services that, as noted below, build trust, support client choices, set achievable goals and empower positive results.

- Build trust: Being clear with clients about what will be done by whom, when and why, and setting consistent expectations, keeping in regular touch and supporting client-driven goals.

- Create collaboration: Engaging clients in building their case plans and making decisions about their cases, as well as including them in planning and developing agency services.

- Set goals: Establishing objectives that are tailored and individualized to the client’s interests and breaking down goals into manageable tasks.

- Empower change: Helping clients build executive functioning skills through modeling and practice, and acknowledging clients’ strengths, validating and affirming their successes.

- Support success: Offering coaching and mentoring to build relationships and confidence, as well as regularly revisiting case plan goals as circumstances and needs change.

Infusing trauma-informed perspectives into service delivery can strengthen the tools we use to help youth and young-adult-serving organizations. At its core, the approach, like my early experience in Philadelphia, doesn’t require that we step into another’s shoes, but that we engage our clients with compassion and empathy as we begin to fully understand their journey.

Jeanette Hercik, Ph.D., is a senior vice president at ICF International and has three decades of experience in workforce and welfare-to-work systems. Today, she oversees a portfolio of family strengthening projects, which include the National Responsible Fatherhood Clearinghouse and the National Resource Center for Healthy Marriage and Families. Jessica R. Kendall, JD, also with ICF International, assisted in the writing of this article. It is the first of three from ICF on this topic to appear in Youth Today in the coming months.

More related articles:

Playing Offense: Behavioral Health Interventions During Adolescence Is Our Best Shot

Traumatized, Locked Up, LA Girls Starting to Get More Help