When Susan Patrick was a little girl, she loved first grade at Woodley Gardens Elementary School in Rockville, Maryland. She remembers moving actively around the classroom and learning at her own pace.

It was only after she left Woodley Gardens that she realized her early experience was not the norm. She had been in a self-paced classroom.

Susan Patrick

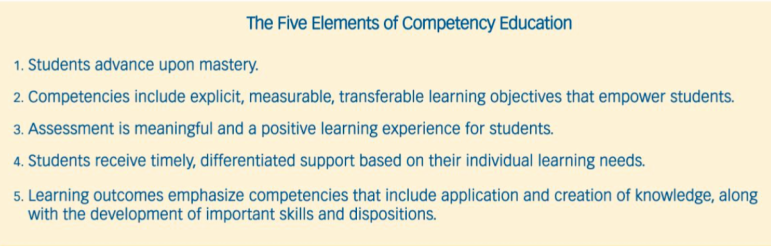

Now president and CEO of iNACOL, the International Association for K-12 Online Learning, Patrick is an advocate of competency-based education. In this approach, students advance through school as they master lists of skills and knowledge known as competencies. It contrasts with the practice in most schools of advancing students based on credit hours in courses.

Competency-based education is praised by many after-school leaders because it offers the possibility of meshing the educational activities of after-school and summer programs with classroom schooling.

How competency-based education works

When kids walk into their classroom in Lindsay Unified School District in Lindsay, California, they see a large chart on a wall, listing each student’s name and a series of “learning standards.” Students check the chart to see which standards they have already mastered and which they must undertake next. Then they turn to another chart that tells them what to do to meet the next standard.

They may be directed to do a project or answer questions from a textbook.

They may even be asked to do role playing to demonstrate what they know to their teacher, according to a description in EdSurge, an educational technology company that provides information to venture capitalists and educators.

Students in the class who are progressing as expected may be grouped together by the teacher (called a learning facilitator) for a short lesson on new material. Students who are behind will get one-on-one assistance. Those moving faster than the rest may continue at their own pace.

Teachers frequently group and regroup students, depending on how the students are progressing, according to EdSurge.

When a student is ready to be assessed, he or she takes an online test. Teachers in Lindsay Unified School District, which has nine schools and more than 4,000 students, examine the test data frequently and regroup students as they master various competencies.

The approach maximizes use of technology, according to the district’s strategic plan, and all curriculum is online.

An array of names

Called by a slew of different names — proficiency-based, outcomes-based, mastery-based or personalized learning — the approach is being used in communities around the country. Forty-two states have created policies that allow for personalized instruction and the creation of competency-based systems, Patrick said. New Hampshire has required all high schools to devise competencies.

Individual districts using the approach include Chugach, Alaska; Adams County, Colorado; Lake County, Florida; Charleston, South Carolina; Henry County, Georgia; and Kennebec Intra-District Schools, Maine.

The after-school connection

When a school moves to a competency-based system, young people can acquire school credit for knowledge and skill outside school.

After-school programs around the country are concerned with helping young people develop skills they think will be needed in a changing economy.

After-school advocates see themselves as meeting the needs of kids in a way that schools are failing to do because of “antiquated teaching practices,” according to a July 2015 Afterschool Alliance report.

“For the youth of today to thrive in the 21st century economy, they must have opportunities to develop, practice and demonstrate a wide array of skills and abilities,” the Alliance report noted.

After-school programs generally don’t use formal classroom instruction, focusing instead on learning by doing.

“We think the work that afterschool practitioners have done to create student-centered learning experiences focused on the development of skills could also be an opportunity for collaboration with K-12 educators,” the American Youth Policy Forum asserted in a January 2016 report, “The Intersection of Afterschool and Competency-Based Learning.”

The collaboration between school and after-school is happening in a few places.

For example, the Providence After School Alliance (PASA) in Providence, Rhode Island, offers a hub that connects the work high school kids are doing in various after-school programs — in debate, environmental science, video game development, for example — to school standards. Through the PASA Hub, community-based after-school providers collaborate with teachers to assess and obtain school credit for the work.

What makes it possible is the school’s switch from crediting students based on “seat-time” in a course to crediting them for meeting proficiencies or competencies.

Schools in New Hampshire are encouraging students to undertake extended learning opportunities outside school for which the student gets credit. The student works with a teacher, a school extended-learning coordinator and a community-based mentor or organization.

[Related: In New Hampshire, Kids Add to Their Education by Leaving School]

“What’s so exciting is that when you have a personal learning plan and all the competencies are identified, you can really start to bridge formal learning in school and informal learning after school,” Patrick said.

Filling in the gaps

Competency-based programs have been shown to have positive outcomes, Patrick said, and may especially benefit lagging students.

“It has the biggest effect on students that were further behind,” she said. “They were able to catch up, accelerate and get back on track.”

A 2015 RAND Corp. report for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation found that students made greater gains in math and reading in schools using personalized learning methods.

Traditional schools move students ahead when the school year ends, and many students may have only gotten 75 percent or 80 percent in a subject, Patrick said. This leaves gaps in their knowledge, she said. It’s especially problematic in subjects like math, which directly build on prior knowledge.

“Over time those gaps get bigger and bigger,” she said. “We put students in a position that’s really hard for them when they haven’t achieved success.”

“We know that even of the students that are graduating from high school, 30 percent to 40 percent of them are needing remediation when they enter college,” she said. It’s a big issue across the system and one that competency-based education addresses, she said.

What critics say

The RAND report noted that schools using this method also use more technology. Tech companies clearly stand to gain.

If a school reform is all “about the tech,” steer clear, warns education writer Alfie Kohn. If personalized or competency-based learning “is presented from the start as entailing software or a screen, we ought to be extremely skeptical about who really benefits,” he wrote in a blog.

Competency-based learning is not about the technology, however, Patrick said.

Other critics warn of teaching skills at the expense of knowledge. Education takes “seat-time,” argues Johann N. Neem, associate professor of history at Western Washington University.

“The purpose of liberal education — unlike vocational education — is not to train but to change people,” he wrote.

“Fostering students’ curiosity about the world requires that they be immersed for a part of their lives in an environment that treats intellectual inquiry — not demonstrating competence — as the highest goal,” he wrote.

The focus on teaching workforce skills can foster a limited view of education and also serves the interests of corporations rather than the students themselves, according to Kohn.

He also questions the assumption that a curriculum can be broken down into small pieces that are acquired one right after another and assessed with discrete questions, as on “contrived tests and reductive rubrics.”

To Patrick, however, the value of competency-based education is clear: Kids are falling behind in school, dropping out or graduating with great gaps in their knowledge.

“Why have a system that allows that?” she asked.

More related articles:

White House Rolls Out Summer Opportunity Plan

Helping Young Veterans Find Work after Military Service

President’s Budget Proposal Aims to Help Youth Get First Job