Back to main post “Orderly Conduct: Classes Offer Dos and Don’ts for Dealing With Police”

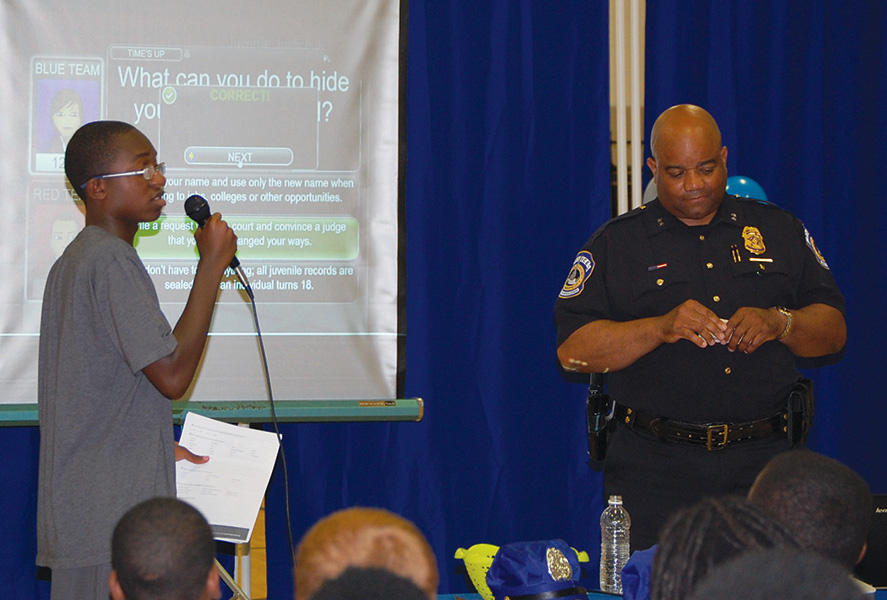

Photo courtesy of the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department of Public Safety

An Indianapolis police officer and a young person engage in Juvenile Justice Jeopardy at the department’s inaugural kickoff of the game at the Ransburg YMCA in Indianapolis.

When Indianapolis assistant police chief James Waters approached local business owners about providing financial support for “Juvenile Justice Jeopardy,” an interactive game that teaches young people about the law and how to interact with police, he didn’t have to do much convincing.

Business owners not only provided $15,000 to purchase 10 licenses to use the game, which is created on a customized basis by a Massachusetts-based nonprofit called Strategies for Youth, but a local mall and restaurants also pitched in by providing food and gift cards as incentives for young people to participate, Waters said.

“The whole idea has been literally validated with community buy-in,” Waters said of Juvenile Justice Jeopardy’s success in Indianapolis.

“We’ve done it at churches, clubhouses, YMCAs, middle and high schools,” Waters said. “We do it wherever somebody wants us to be.”

Once Waters got promoted to assistant chief, he got every police district in the city to offer the game on a weekly basis. Now, he says, the Indianapolis police department reaches about 100 kids per week through the game. Indianapolis has an estimated population of about 843,000, and one-fourth of the population is under age 18.

“My goal was to build a relationship with our teenagers,” Waters said.

“Kids don’t usually get criminal law until college,” he continued. “But we hold them accountable for violating it. So what makes sense is we would want to get them together and say: Here are some common things that kids get arrested for that they just don’t know about.”

For instance, Waters said, officers use Juvenile Justice Jeopardy to teach young people about how they can be arrested for just riding in a stolen car. Or how, if police find gun or drugs in the car, they could be arrested for those things as well by way of “constructive possession.”

“We pose the questions, get the answer and have discussion,” Waters said. “One of the things that are commonly misunderstood is can a male officer search a female? Most people say no.

“Sometimes we can and must under certain circumstances, and it’s good for them to know that because we don’t want them resisting the search. Just merely resisting the search can get them arrested, and really for what? They are ignorant [of the law].”

Waters said every district police commander in Indianapolis has at least one community relations officer trained and licensed to use Juvenile Justice Jeopardy.

Some of the young people who encounter the game may be standoffish at first but eventually warm up to the police, Waters said.

“On the way out the door, they’re shaking our hands,” Waters continued. “They go from this attitude of defiance to gratitude in just 45 minutes. It really transforms relationship and attitudes with kids toward police.”

The game has also enabled Indianapolis police to build meaningful relationships in tough neighborhoods with histories of hostility toward police.

Waters hopes the game ultimately leads to a reduction in disproportionate minority confinement, as well as a reduction in violence toward police.

To get greater insight into the game’s impact, the Marion County Commission on Youth may compile self-evaluations that officers give to program participants after each session.

“We want to build positive, honest and genuine relationships between young people and law enforcement, and JJJ seems to be a way that can be accomplished,” said John Brandon, president of the commission, which has helped coordinate game sessions.

Waters hopes to use the data from the evaluations to apply for grants to expand the Juvenile Justice Jeopardy game in Indianapolis.

Back to main post “Orderly Conduct: Classes Offer Dos and Don’ts for Dealing With Police”