Stell Simonton

The vision of the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child is a world in which all children are respected, protected and have a fair start in life. Here, a boy looks at an exhibit on human rights in the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta.

“Every child deserves a fair start in life,” said UNICEF Executive Director Anthony Lake. “What can be more important than that?” He spoke those words in January as Somalia ratified the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child, becoming the 195th nation to do so.

Sitting in the wings, unwilling to ratify the Children’s Rights Convention, were the United States and South Sudan, the only two holdouts among all the countries in the world, which is ironic since the United States was actively involved in drafting the Children’s Rights Convention 25 years ago.

Created in the United Nations and adopted by that body in 1989, the Children’s Rights Convention (CRC) represented “the first time children were recognized as rights holders in an international treaty,” according to the U.N. Committee on the Rights of the Child, and sets standards for education, social services, health care and justice for children around the world. American delegates were active in drafting the document, suggesting, for example, the sections on freedom of expression and freedom of association, according to Human Rights Watch, an organization that defends human rights internationally.

Stell Simonton

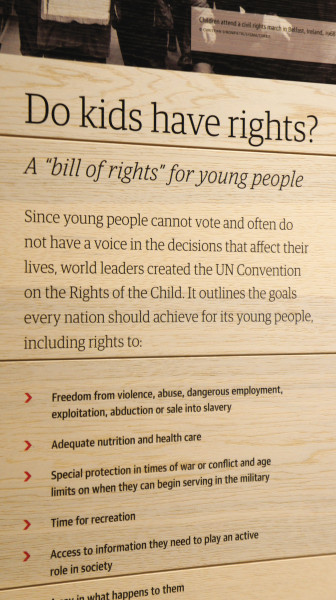

The U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child functions as a “bill of rights” for children around the world.

A year after U.N. adoption, the convention was ratified by 20 countries and took effect. The U.N. and human rights advocates around the world celebrate the CRC’s 25th anniversary this year.

The agreement requires governments to protect the rights of children, starting with the basic right of survival, according to Human Rights Watch. Children must also be protected from abuse, neglect and exploitation.

By the end of 1990, 63 countries had ratified the agreement. Three years later, 153 had signed on, making it one of the most widely adopted human-rights agreements in the world.

“The CRC was and is a milestone in promoting the welfare and protection of children everywhere,” Unicef’s Lake said in a 2011 speech at the Harvard Conference on Adolescent Rights.

Because it is an agreement among nations, the CRC has the status of a treaty. In the United States, the president must send a treaty to the Senate and get it approved by a two-thirds majority vote order for to be ratified.

Twenty years ago, Madeleine Albright, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, signed the convention on behalf of President Bill Clinton signaling Clinton’s intent to get it ratified. But no U.S. president has yet sent the treaty to the Senate for ratification.

“It’s the best opportunity to advance the well-being of children,” said Jonathan Todres, professor of law at Georgia State University College of Law, who serves as an advisor to nongovernmental organizations working on policy to address trafficking and exploitation of children.

Many children risk not getting needed health care or quality schooling, he said. They risk being trafficked, or of being exploited as child labor. (See sidebar “Has the Children’s Rights Convention Made a Difference?”)

“If we look both globally and nationally, we can do a lot better for children,” Todres said.

“The CRC is the most comprehensive, legally binding document that would provide coverage for and support the rights of children and their well-being,” Todres said.

The cold shoulder

So, why has the United States failed to ratify a human-rights agreement it helped create?

“There was a lot of organization by conservative groups in the U.S. to oppose the convention,” said Jo Becker, advocacy director of the children’s rights division of Human Rights Watch. Evangelical groups and parents rights organizations led the opposition, she said.

Michael Farris, chancellor of the evangelical Christian Patrick Henry College, in Purcellville, Va., president of ParentalRights.org and chairman of the Home School Legal Defense Association, asserted in a column on townhall.com that under the language of the Children’s Rights Convention, “no family is safe from governmental intrusion.” ParentalRights.org is a leader in opposing the Children’s Rights Convention, asserting that parents are losing their rights and the family is being undermined. The organization also advocates a parental-rights amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The Home School Legal Defense Association published on its website a concern that parents would no longer be able to spank their children if the agreement were ratified. Other concerns are that parents would not be able to opt their children out of sex-education classes.

Opponents of CRC also argue that U.S. ratification would undermine U.S. sovereignty “by giving the United Nations authority to determine the best interests of U.S. children,” according to a Congressional Research Service report to Congress in 2013. This report notes a variety of issues concerning opponents — and supporters of the CRC — from parental rights and privacy, to family planning and abortion (“the Convention’s definition of a child as ‘every human being below the age of eighteen years’ intentionally does not set a lower age limit, leaving the States Parties to determine where life begins”).

Supporting the treaty

Numerous child-welfare organizations support the CRC, however. That same 2013 congressional report noted supporters say “U.S. ratification would strengthen the United States’ credibility when advocating children’s rights abroad.”

“There is a fear and misunderstanding about what the treaty is going to do,” said Christine James-Brown, president and CEO of the Child Welfare League, a coalition established in 1920 of private and public agencies that serve children and families. “Some fear that it takes away the roles and responsibilities of parents,” James-Brown said.

That’s not the intention, she said.

Stell Simonton

A mother and young daughter in Atlanta stand before a photo of Nelson Mandela in the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, which educates the public about human rights struggles around the world.

“The treaty provides a set of principles” and sets an important reference point for what is needed at a global level, she said. For example, it says children should be protected and educated and not go hungry, she said.

There’s also the feeling among some people that “no one should tell us how to raise our kids,” James-Brown said.

“The treaty itself defines the need for families and the importance of families,” she said. “Families are crucial to children.”

Todres pointed out that 19 provisions in the Children’s Rights Convention carve out a role for the family.

Becker, of Human Rights Watch, said the convention repeatedly refers to the authority of parents to raise their children. That organization has published several spotlights on its website noting practices in violation of the convention’s prohibitions that should be ended, such as U.S. child labor laws that allow children as young as 12 to be put to work in agriculture, but asserts they are “not a barrier to ratifying the convention.”

The United States is already in compliance with most provisions of the treaty, Todres said. Opponents say this makes the treaty unnecessary.

A U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2005 did away with the death penalty for minors. However, the United States allows life sentences without the possibility of parole for minors who have committed some crimes — a practice the treaty opposes.

Still, court decisions in the United States have actually been moving away from life sentence for those who committed crimes as minors, Todres said.

Providing a comprehensive approach

“The treaty provides a set of principles” needed for people to rally around, James-Brown said.

“There’s no consistency state-to-state and county-to-county on what services children and families need,” she said. “I don’t want to live in a country where some children get their needs met and others don’t based on where they live.

“The Child Welfare League was established with a vision that every child in every ZIP code could have access to high-quality services,” she said.

Although it hasn’t ratified the treaty, the United States has ratified two related agreements known as optional protocols. One is a statement against the use of child soldiers and the other protects children from sexual exploitation.

“Our support for the convention is because it sets an international standard for the human rights of children,” said Carol Smolenski, executive director of ECPAT USA (End Child Prostitution and Trafficking), part of an international nongovernmental organization based in Thailand.

In its work overseas, ECPAT fights the sale of girls into prostitution.

Since the Children’s Rights Convention is an international agreement on children’s rights, it would strengthen ECPAT’s efforts in opposing what’s defended as a cultural practice, Smolenski said.

To James-Brown, organizations that support the Children’s Rights Convention have a responsibility to speak out about what it does and does not do. They should push for its ratification, she said.

“The U.S. has played such a leadership role” in drafting the treaty and in urging the improvement of conditions for children around the world, she said.

“We should not be the only country that has not signed it,” she said. “The world is looking at us.”

Access to Health Care and Education

Children should have access to health care services so that they may enjoy “the highest attainable standard of health,” the Children’s Rights Convention states. It also protects children’s right to education. Primary education should be compulsory, and additional education should be made accessible “by every appropriate means,” it states.

Who’s getting an education?

In the United States, a big gap exists in the quality of education available to children.

According to a 2014 U.S. Department of Education report, black, Latino and Native American students are far more likely to have inexperienced teachers, to be suspended and not to be offered some essential courses in math and science.

A 2012 Schott Foundation for Public Education Report found that black and Hispanic children were four times more likely to be enrolled in New York City’s poorest-performing schools than white children.

Globally, 57.8 million elementary school-age children are not in school at all, according to UNESCO’s Education for All Global Monitoring Report. Girls have less access to school than boys, the report said.

Who gets health care?

The Children’s Health Fund reported in 2006 that more than one-fourth of children in the United States lack adequate access to health care because of lack of insurance and a shortage of doctors in rural areas.

Health insurance coverage has improved although it varies widely among states, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2006, 11.7 percent of children across the nation lacked health insurance, but the number dropped to 7.6 percent by 2013, according to the Census Bureau. The Kaiser Family Foundation credits the expansion and simplification of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Around the world, an estimated 9.7 million children under age 5 die each year from preventable causes, according to UNICEF. Much progress has been made since 1990 in reducing early childhood deaths, but far too many children still lack the care they need, according to the organization.

See sidebar “Has the Children’s Rights Convention Made a Difference?”