Elaine Korry

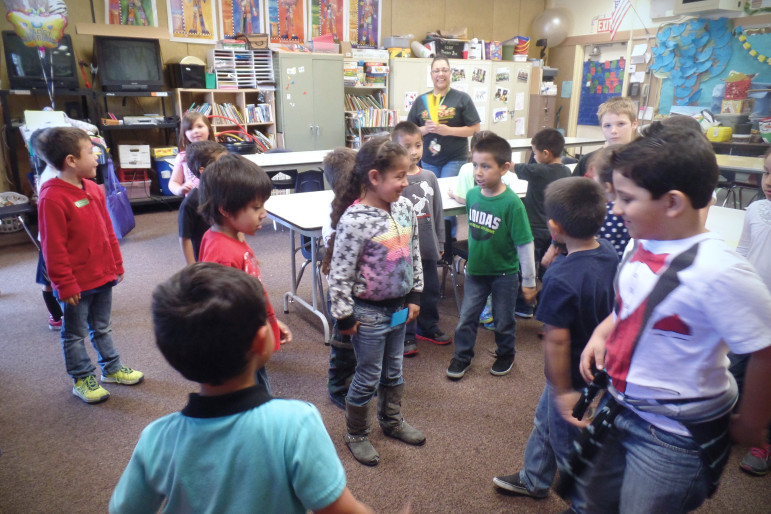

When the regular school day ends, students gather in Room 9, the after-school center at Los Molinos Elementary School, for several hours of homework help, enrichment activities and recreation before heading home to their families.

After-school activities fill a gap in remote communities, but administrators struggle to fund youth-development programs

LOS MOLINOS, Calif. — In a corner of Room 9, the after-school center at Los Molinos Elementary School, a dozen youngsters are wriggling their bodies and jumping up and down in time to music pulsing from a CD player. After several songs and a few minutes of stretching, the children settle down, taking their seats at two long tables. Bilingual after-school instructor Marybel Torres then has the kids take out their notebooks and get started on homework. The SERRF program — Safe Education and Recreation for Rural Families — has begun.

[module type=”aside” align=”right”] 2.5 million children living in rural areas live in deep and persistent poverty.

2.5 million children living in rural areas live in deep and persistent poverty.

From National Network of Statewide Afterschool Networks

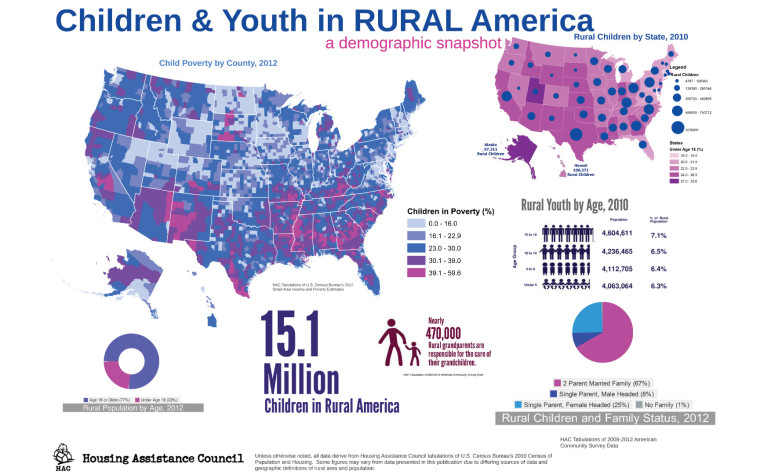

[/module]California is one of the nation’s most urbanized states. Even so, about 13 percent of its children live in remote or sparsely populated areas, according to the U.S. Census — some in entirely rural counties, others in places with pockets of development amid vast deserts, mountains or wilderness regions.

Nationwide, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, an even higher proportion of children — about one in five — is considered rural. For the nearly 10 million kids growing up in these small towns or frontier outposts, a publicly funded after-school program is often their only opportunity for extracurricular activities or expanded learning.

“There’s not a lot of other activities around here,” said SERRF facilitator Bill Hardwick. “There’s t-ball and Little League for the older ones, but that’s about it. If they weren’t here, the majority of the kids would be in front of the TV or playing video games.”

About 320 children attend this pre-K through eighth-grade school in Los Molinos (population 2,037), which is tucked among the walnut groves and plum orchards of Tehama County, 180 miles northeast of San Francisco. The after-school program has 75 youngsters enrolled, many of whom are Hispanic, reflecting the influx of immigrants to this agricultural community. According to its latest state accountability report, 82.5 percent of the students at Los Molinos Elementary are “socioeconomically disadvantaged,” living near or below the federal poverty level.

The SERRF program is one of approximately 4,500 after-school programs in California, serving nearly half a million low-income elementary and middle-school students. Most rely on funding from the state’s After School Safety and Education (ASES) Program, which was created by a voter initiative passed in 2006. The programs vary greatly in size, and in their administration: Some are operated by the school district, others by the county, and still others by nonprofit organizations with contracts to run dozens of sites throughout the state.

Fewer choices in rural America

Whether in California or the rest of the nation, one trend is clear: Students in rural areas, who have less access to enrichment activities to begin with, also are less likely to participate in a quality after-school program than their urban or suburban peers.

“Definitely there’s an imbalance,” said Erik Peterson, vice president of policy at the Afterschool Alliance, a nonprofit advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C. “There’s a need for more funding for rural programs.”

“America After 3 PM: From Big Cities to Small Towns,” a 2010 report by the Afterschool Alliance, found that 18 percent of city kids are enrolled in an after-school program, compared to only 11 percent of rural children. And yet the demand for these programs is high, according to Peterson. “Parents of 4.1 million rural children who are not in an after-school program say that they would enroll their child in a program if one were available to them,” he said.

Homework help and enrichment

The SERRF program at Los Molinos runs from 2 to 6 p.m. each school day, starting with a healthy snack, followed by an hour of homework help. As children work on their assignments, Torres, who has been with the program for nearly 12 years, checks in with those English language learners she knows won’t be able to get help at home.

“The kids — their English is pretty good,” said Torres, “but many of their parents would be lost trying to help with their reading or math homework.”

[module type=”aside” align=”right”] One-fifth of children in the U.S. attend public schools in rural communities.

One-fifth of children in the U.S. attend public schools in rural communities.

From National Network of Statewide Afterschool Networks

[/module]“My mom knows some English, but my dad, not really,” said 10-year-old Briseyda Morfin, whose most challenging subject is science. With two brothers and two sisters at home, Briseyda said it’s “really loud” at her house, so she finds it hard to concentrate on schoolwork. “I like to get my homework all done at school and have it all finished,” said Briseyda. Afterward she still has time to play with her friends before it’s time to go home.

Isabella Searcy-Chamness, 12, agreed that the SERRF program keeps her on track academically. “Otherwise I would just watch TV all day and not do my homework,” said Isabella. “This way I can have better grades.”

After homework is done, the kids enjoy an hour of enrichment, which includes art programs, drama, music or perhaps a field trip to the Schreder Planetarium in Redding, Calif., nearly 50 miles away.

The fifth-graders are working with a GEMS (Great Explorations in Math and Science) curriculum kit called Crime Lab Science, in which they try to solve a mystery by looking for clues and analyzing data to choose the right suspect.

The SERRF program winds down with an hour of recreation before they get picked up by a relative or neighbor or the school bus takes them home. By that time, the hope is most of the kids will have adult supervision, even though many parents work long hours in the surrounding fields.

“Some of these kids would be running the streets,” said Torres, “probably involving themselves with a group that is no good. So we keep that positive community atmosphere for these kids to stay out of trouble.” Teens in the community also rely on their school to fill a gap in extracurricular activities; Los Molinos High School has an athletics program and several clubs and student organizations designed to keep kids safe and engaged after school.

The only game in town

Jan Banning

“In rural America, the school is the natural hub of activity,” said Susan Maschmeier, after-school director at South Bay Union School District in Eureka, Calif., 100 miles south of the Oregon border. “We do not have the abundance of community centers, museums or arts programs to begin with, so it’s more difficult for families to access enrichment activities, even if they have the money.”

Rural areas also tend to have higher poverty levels (see sidebar), and less access to transportation, so many families couldn’t afford to send their kids to ballet lessons or a theater workshop, even if those activities were available. The closest YMCA or 4H club could be hours away, so parents in rural areas count on their local schools to provide extracurricular activities, and that expectation ramps up the pressure on administrators to meet the needs of their families.

[module type=”aside” align=”right”] Thirty-one percent of rural grade-school students are eligible for reduced-price or free lunches, as compared to 25 percent of urban grade-schoolers.

Thirty-one percent of rural grade-school students are eligible for reduced-price or free lunches, as compared to 25 percent of urban grade-schoolers.

From National Network of Statewide Afterschool Networks

[/module]Programs in California benefit from one of the most generous electorates in the nation — $550 million is guaranteed annually by voters to out-of-schooltime programs in the state through ASES. In addition, state lawmakers recently passed SB 1221, legislation that will provide up to $15,000 per year in transportation funds for the most remote districts where schools are designated as “frontier.”

Michael Funk, director of the after-school division at the California Department of Education, said that policy fix should help ease the transportation woes of programs in the most rugged parts of the state. “I’ve visited a place called Happy Camp where in wintertime the kids are walking home after school in the snow on a winding mountain road with a cliff that drops off the side,” said Funk. “The road was barely wide enough for a car,” he said. “It’s crazy what some of these kids need to do.”

SB 1221, which was signed by Gov. Jerry Brown, also increased the minimum grant size for after-school programs. Starting in July, the minimum grant will be $27,000, no matter how small the school, which Funk said will enable programs to hire a second staff member, at least on a part-time basis.

But California is a definite outlier when it comes to state support for after-school programs. Only 18 states (Arizona, California, Connecticut, Washington D.C., Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Tennessee and Wyoming) directly fund after-school programs. “State funding is about 3 percent of the total budget for after-school, and a big chunk of that is California,” said Peterson. “The vast majority of funding — 76 percent — comes from parent fees,” he said. The next biggest funding source — federal funding — accounts for 11 percent.

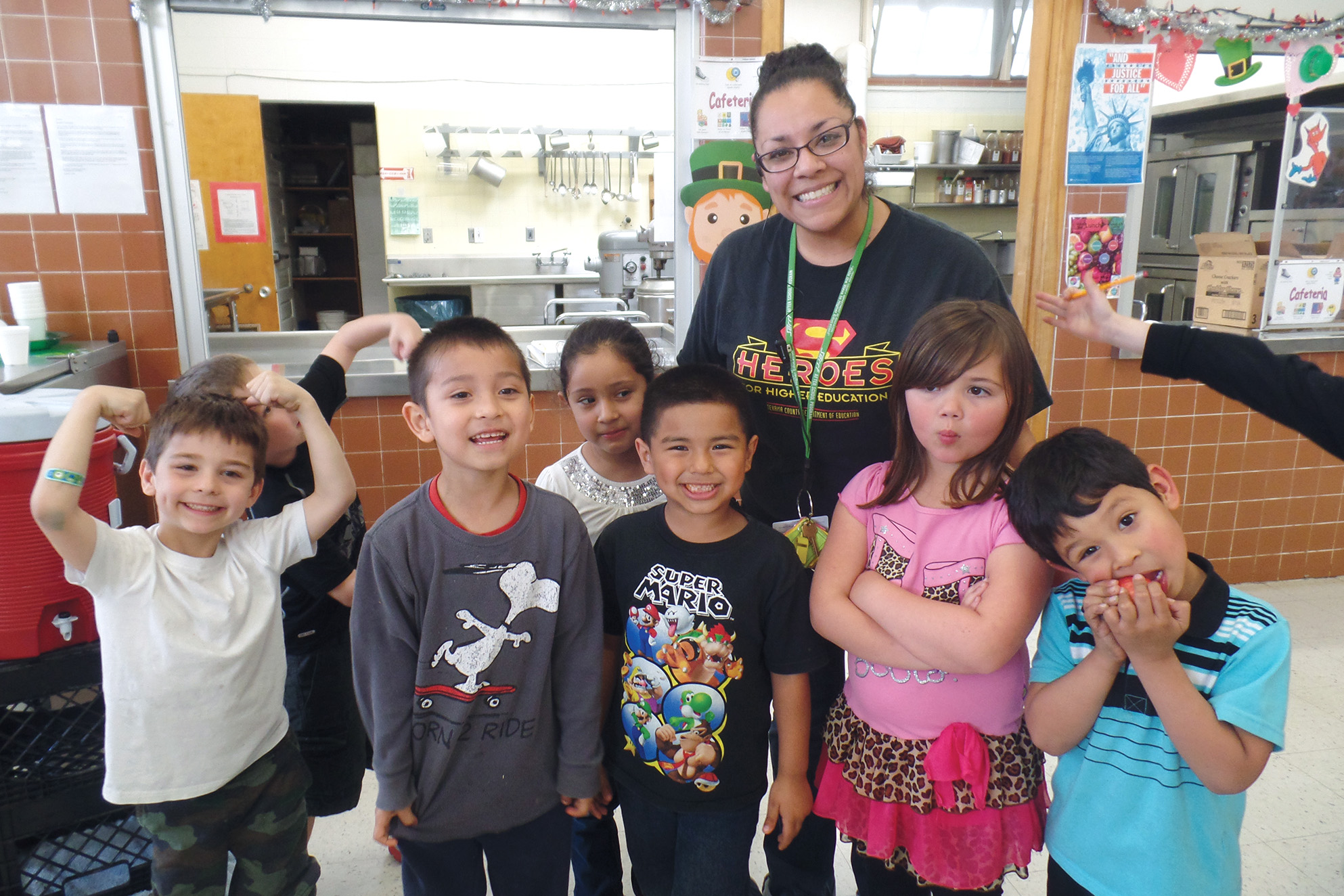

Elaine Korry

In the school cafeteria, bilingual instructor Marybel Torres makes sure her students start their after-school program with a nutritious snack.

And the sole federal funding stream exclusively for OST programs — 21st Century Community Learning Centers — doesn’t fill the gap, Funk said. “When we put out a request for grant applications for 21st Century dollars, we typically are able to fund only 10 percent of all those who apply,” he said. “There is that much demand.”

Nationally, only one out of three requests for federal funding is awarded, according to the Afterschool Alliance. “Over the past 10 years, $4 billion in local grant requests were unable to be fulfilled because of a lack of adequate federal funding,” said Peterson. At presstime, the current funding level is not secure as negotiations continue in Washington over reauthorization of 21st CCLC.

As a consequence, rural providers have become expert at juggling small pots of money to balance their budgets, chasing after tiny grants from community organizations and partnering with anyone committed to the cause.

“When you want to be able to do extra things in a small school district, you have to be creative,” said South Bay Union School District’s Maschmeier, “especially when it comes to resources — manpower, materials and in program design.” She said people in rural districts can’t afford to exist in a tiny niche. “Everyone has to wear more than one hat to keep the program alive.”

See sidebar “After-School Programs Needed, But Scarce in Poorly Funded Rural Areas”

Elaine Korry is a freelance print and public radio reporter based in the San Francisco Bay Area.