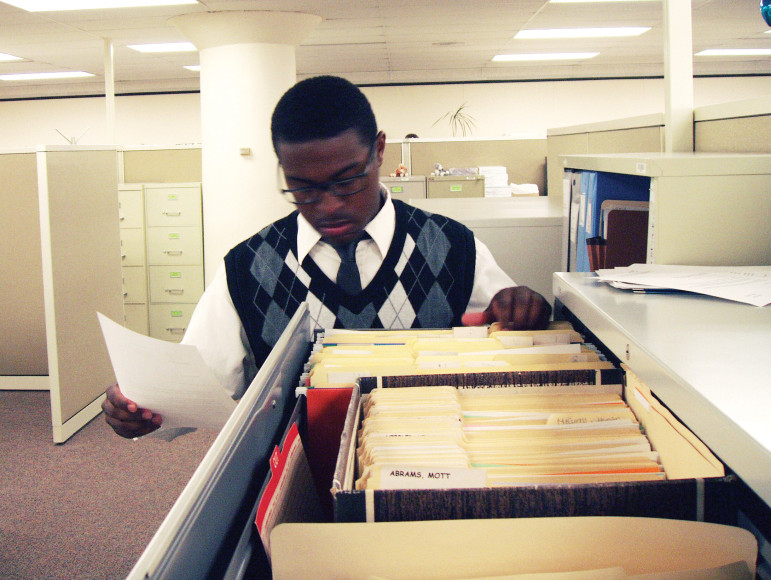

Photos courtesy of Milwaukee Department of City Development

Summer youth employment interns work with Milwaukee’s Department of Public Works to clean city neighborhoods as part of the city’s Earn & Learn program

When Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett calls local employers and foundation leaders to drum up support for “Earn & Learn” — a summer jobs program he launched a decade ago — he speaks in plain terms about the benefits of providing young people the chance to work.

“One of the first pitches I make is: You remember your first job. Everybody remembers their first jobs,” Barrett told Youth Today.

“Whether positive or negative, it’s a really life-shaping event, and to me, it’s important that we give teenagers, particularly in economically distressed neighborhoods, a chance to have that exposure,” Barrett said. “I feel very passionate that we as adults have a moral obligation to create hope and opportunity in young people’s lives.”

Mayor Barrett’s pitch to the worlds of business and philanthropy has evidently paid off.

Despite an overall decline in federal funding for summer jobs programs, Milwaukee’s Earn & Learn program — which links young people to employers that range from the local power company to powerhouse law firms — has done more than just stay afloat. It has also grown to serve more young people than ever in its 10-year history.

Back in 2006, Mayor Barrett said, the program provided summer jobs to about 900 young people. Last year, he said, that number grew to about 3,000.

“We have to turn people away,” Barrett said. But he said he viewed the excess demand for summer jobs as a “positive sign that a lot of young people want something to do for summer.”

The program, which is operated by the Milwaukee Department of City Development in conjunction with the Milwaukee Area Workforce Investment Board, has three components:

- Community Work Experience Program: Students ages 14 through 21 work at local nonprofits and community organizations.

- City Summer Youth Internship Program: Students ages 16 to 19 work for one of 13 city departments — from the city’s police, fire and public works departments to the housing authority and mayor’s office — and learn about jobs in local government. They must commit to the eight-week program and be residents of a Community Development Block Grant area. Each Friday the interns talk to representatives from local colleges and enhance their personal and professional work skills. Students must list at least one personal reference in their online applications. Interns earn $7.50 per hour and work 20 hours per week.

- Private Sector Job Connection: Students 18 and older work for a local company and get “real world experience.” Employers fill out “job orders” with the city that indicate the wage they are offering to pay and the job duties. The city screens applicants to ensure a match with the employer’s specifications, then refers appropriate candidates.

Part of how Barrett has kept the summer jobs program growing despite less federal funding is through the Mayor’s Earn & Learn Fund, an account the mayor set up in 2011 at the Greater Milwaukee Foundation.

“I would call businesses and foundations and ask them to contribute,” said Barrett, a former five-term U.S. congressman who got elected as Milwaukee mayor in 2004.

The first year, the city raised $322,000 for the fund, the mayor said. By 2014, he said, the figure had more than doubled to $661,000.

While the increase in private funding amid declining federal funding for summer jobs is positive, a report released earlier this year from JP Morgan Chase & Co. warns that it is not enough to create a “fully effective, sustainable model for public–private partnership on youth employment.”

“Rather, it is essential for private sector employers to get more deeply engaged with their partners and local officials to support the creation of high-quality programs that are aligned with local workforce needs,” states the report.

Teens enrolled in Milwaukee’s summer youth employment program work in one of three program components: Community Work Experience, Summer Youth Internship Program and Private Sector Job Connection.

Titled “Building Skills Through Summer Jobs: Lessons from the Field,” the report features Milwaukee as one of 14 cities that share in a $5 million contribution JPMorgan Chase made through “New Skills at Work,” a five-year, $250 million global workforce readiness initiative.

Barrett concedes that the city does not track outcomes in terms of future long-term employment.

“A lot of the evidence is anecdotal,” Barrett said. But he added that local law firms, blood centers, engineering firms and other employers that participated in the program have hired some of the young summer job participants into some kind of a permanent job.

“What better testament is there than that?” Barrett said.

He has also heard from program alumni who said their summer jobs opened the doors to future employment.

“There’s nothing I like more than being stopped in a grocery store by a young person that was helped by Earn & Learn,” Barrett said.

While a full-scale evaluation may not be available, a review of some subcomponents of the program shows that program coordinators are — at the very least — cognizant of the need to get better at ensuring a positive work experience for young people.

For instance, one report from the Student Conservation Association’s Milwaukee Conservation Leadership Corps provides a candid assessment of some of the issues and challenges it faced as the program dispatched young workers to do tasks ranging from building and maintaining trails to constructing fences and managing invasive species.

The report reveals crew members felt their “leadership opportunities and advanced work skills training were inadequate,” and program leaders reported plans to be “more intentional” about addressing those things in 2015.

The SCA report also deals with some of the young workers’ harsh economic realities — one being that they wanted to work too much.

“Many of our members work multiple jobs in the summer to save for school and/or help out their families,” the report states. “Two of the members who were not able to complete the program held jobs outside of the summer program.

“A number of motivational problems among members were also believed to be linked to some members’ lack of sleep due to other work commitments outside of the program,” the report states. “While the decision is difficult, it is the recommendation of Crew Leaders and program manager to strongly discourage ‘moonlighting’ by members in the future.”

Continuous improvement issues aside, the reality is there could be no effort to improve if the program didn’t garner the funds to exist.

Mayor Barrett’s fund-raising efforts have proven crucial in this regard. Back in 2006, in the program’s infancy, the lion’s share of funding — about $1.2 million — came through the Workforce Investment Act, and not much came from private funders.

But with a decline in federal money, local proponents of summer jobs programs had to tap into other sources.

“It’s pretty clear to everybody that the federal government — at least in the short term — is not gonna have the money to put into these jobs as much as we would like to see,” said Don Spangler, policy advisor for the National Youth Employment Coalition.

Indeed, Milwaukee only got about $250,000 in WIA funds for summer jobs in 2014, as opposed to the $1.2 million it got back in 2006.

MacArthur Weddle, a member of the Milwaukee Area Workforce Investment Board’s Youth Council, which is responsible for promoting and leveraging funds for youth programs, said while the workforce board works hard to promote summer jobs in Milwaukee, the program could not flourish the way it has without the mayor’s personal touch.

“I don’t think we would have the number of hired young people if it wasn’t for the mayor and his commitment to young people,” Weddle said.

Weddle — who serves as executive director of the Northcott Neighborhood House, a recreation and education center on the city’s north side, which also provides summer jobs through the program — said he has met program alumni who told him their career success was directly related to their summer job experience. He speaks of young people who are now branch managers at banks who got their first experience working at a financial institution through the summer jobs program in Milwaukee.

Weddle also said Milwaukee has a “really good” set of foundations — such as the Helen Bader Foundation, the Greater Milwaukee Foundation, the Bradley Foundation and the Brewers Community Foundation — that help support summer jobs in the city.

“They’re really reaching out to help make a difference in helping to secure dollars so we can do better programming and serve more youth,” Weddle said.

For a look at JP Morgan Chase & Co’s summer youth employment report, “Building Skills Through Summer Jobs: Lessons from the Field,” go to http://bit.ly/1CjLeaJ

See sidebar “More Than a Salary: Summer Job Provides Important Lessons on Work and Life”