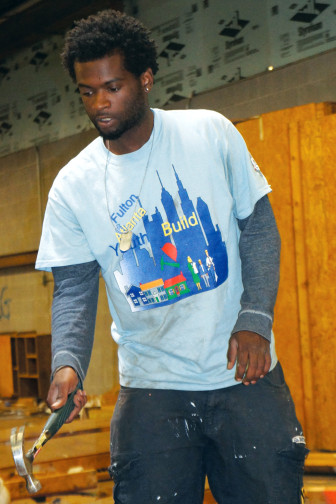

Stell Simonton

Jeffery Johnson, a Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild student, pulls nails from a board in the warehouse of Habitat for Humanity in Atlanta. YouthBuild programs forge relationships with other nonprofits in their community, and Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild sends students to work and learn at Habitat construction sites.

ATLANTA — On a sunny day in October, Aikeem Lawson, 22, was among a dozen or so young adults repairing a dilapidated house in southwest Atlanta, sawing plywood panels and nailing them to walls.

As a teenager, Lawson had dropped out of Chapel Hill High School in Douglasville, Ga. Now, he is on track to earn a GED and gain job skills through Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild.

“It’s a second chance for you to get your life together,” Lawson said of YouthBuild, a national nonprofit, serving 16- to 24-year-olds who get that second chance for earning a diploma and together develop leadership and job skills through service.

Jennifer Rhodes, 22, stood inside a small room bolting plywood. She had attended nearby Southwest DeKalb High School, but left school six years ago.

“I didn’t really want to come [to YouthBuild] at first,” Rhodes said. She just wanted a job to put food on the table each day.

At age 16, Rhodes was kicked out of her house. She lived on the streets for four years and gave birth to a son, who died. Eventually Rhodes found shelter at Covenant House, a service for homeless youth, whose staff encouraged her to apply to YouthBuild.

YouthBuild encouraged her to think in terms of a career.

“I’d probably be still on the streets — or dead, honestly,” she said. “I feel YouthBuild gave me back my hope for the future.”

Tapping into the energy of young people

Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild is one of 264 programs in 46 states — plus Washington D.C., and the U.S. Virgin Islands — affiliated with YouthBuild USA. Together these independent nonprofits serve about 10,000 low-income young adults who work full-time toward a high school equivalent diploma while also learning job skills by building affordable housing in their communities. The program also focuses on leadership development, community service and the creation of a supportive community.

YouthBuild was the brainchild of founder Dorothy Stoneman, who in 1978 asked a group of east Harlem teenagers how they’d like to improve their community if adults helped them.

They told her they would take back the empty buildings from drug dealers and get rid of crime. Stoneman worked with the group to renovate a tenement building.

From this came the YouthBuild philosophy: Tap into the energy and intelligence of kids living in poverty and work with them to transform their community.

Nuts and bolts

Stell Simonton

Bryant Brown (left) and Traneka Samuel took part in the nine-month program offered by Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild, where they studied for a high school equivalency certificate and learned construction skills. Here they pry nails out of used lumber to reclaim it for other uses.

When Lawson, Rhodes and the other participants finished their work on the southwest Atlanta house, they headed back to a low brick building on Kelly Street, in the urban center of Atlanta — office of the Fulton Atlanta Community Action Authority, which sponsors and houses Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild.

Inside, Tim Harrington, a large, soft-spoken man, walked past a rack of glossy black graduation gowns and into an adjoining room, where the shell of a small doghouse sat in the corner.

[module type=”aside” align=”right”]According to figures from YouthBuild USA:

-

77%

of participants in affiliates across the country complete the program.

-

71%

gain a high school diploma, a diploma equivalent such as the GED or an industry-recognized certification in construction or other trade.

-

55%

were placed in a job or in post-secondary education at exit.

Dubbed “Coach Tim,” the construction instructor for Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild began nine months ago teaching this class of 29 students carpentry, starting with the construction of the doghouse. They spent half their day in his construction class and half in an academic class geared toward the general equivalency diploma (GED).

Nearly one-third of the students in this YouthBuild affiliate are female, similar to the percentage nationwide, and most have young children, Harrington said.

The students learned plumbing, electrical, painting and safety skills. But most of all, they started on a path to improve their lives.

“There’s a lot of poverty here,” Harrington said of Atlanta. The students are “caught up in the streets.” Nearly all have been exposed to violence, he said. None of them had completed high school.

A large segment of young adults in the United States are cut off from avenues of opportunity. Fourteen percent of youth ages 16 to 24 are not working or attending school, according to Opportunity Nation, a campaign of the nonprofit Be the Change. Unemployment among this age group is twice as high as overall unemployment, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Young adults in poverty have much less voice in shaping their community and nation than their more affluent peers, according to Peter Levine, associate dean of Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service at Tufts University. Levine was formerly the director of the college’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning & Engagement, which conducted a 2012 evaluation of YouthBuild USA and issued a report describing — among other things — the impact of the program’s model.

outhBuild actively works to give young people avenues for expression. They learn to speak in front of groups, for example. Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild has a policy committee — sort of like a student council — that organizes graduation and makes some program decisions. Nationally, YouthBuild has an alumni association, a Young Leader’s Council and other groups that former participants can join.

A comprehensive approach

Stell Simonton

“It’s a second chance for you to get your life together.” Aikeem Lawson, 22.

“The [YouthBuild] program is set apart by its comprehensive approach,” said Yvonne Beckles-Thomas, director of Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild, which includes focuses on leadership development and counseling, and works to place graduates in jobs or college.

Students spend about 10 percent of their time in leadership-development activities, Harrington said.

Participants learn how to conduct themselves in a job interview and gain the “soft skills” employers are looking for, Harrington said. They also take field trips to local colleges and technical schools in order to encourage or facilitate college enrolment.

“It’s a great pre-apprenticeship program,” said Chris Morrison, coordinator of the Carpenters Training Center at Carpenters Local Union 225 in Atlanta. “It opens up a lot of [young] people’s eyes to the programs that are available in construction.”

Upon graduation from YouthBuild, students are ready to enter the carpentry apprentice program Morrison runs.

According to figures from YouthBuild USA, 77 percent of participants in affiliates across the country complete the program. Seventy-one percent gain a high school diploma, a diploma equivalent such as the GED or an industry-recognized certification in construction or other trade. Fifty-five percent were placed in a job or in post-secondary education at exit.

YouthBuild programs track graduates for a year after completion.

Civic skills

Bryant Brown, 21, credits YouthBuild with teaching him how to talk in front of a crowd without being shy.

“I’ve learned people skills,” he said.

“It brought a lot of us out of our comfort zone,” agreed Rhodes, a member of the organization’s policy group, a youth council that most recently planned the class’ graduation ceremony.

Acquiring and getting the opportunity to use civic skills is enormously important, according to the Tufts 2012 evaluation, “Pathways into Leadership: A Study of YouthBuild Graduates.” The evaluation noted that core aspects of democracy had eroded in the United States: “Unions, religious congregations, voluntary associations, and political parties have lost most of their young members since the 1970s.”

Venues for discussing public issues are dominated by middle- and upper-income Americans, the report noted. Young people who do not attend college are not likely to be drawn into groups and settings where public issues are discussed and solutions are developed. “YouthBuild is one of very few large-scale networks that has the potential to counteract these trends,” the report concluded.

“YouthBuild stands out as a rare and important example,” said Levine of Tufts University.

“What they really try to do is build the kind of alumni groups that a college would have,” he said, so alumni can connect to each other and take leadership roles.

“A certain group of YouthBuild participants get transformed through the experience,” he said.

Obstacles to overcome

But Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild faces a number of challenges.

This year, the local affiliate lost funding when a three-year grant through the U.S. Department of Labor was not renewed. Federal funding for YouthBuild comes through the Department of Labor, with local programs competing for grants.

Stell Simonton

YouthBuild students help build affordable housing in their communities as they further their education and learn job skills. Here Shamoi Ferris and Rashaad Johnson saw plywood to repair a dilapidated house in southwest Atlanta that will be used as an office for the Greening Youth Foundation.

“It’s a common challenge,” said Scott Emerick, vice president of education for YouthBuild USA. “Ideally programs have a diverse funding stream,” he added.

Fulton-Atlanta received a community service block grant but is now looking for foundation assistance, Beckles-Thomas said.

“Some YouthBuild programs have been able to get cities and states to contribute, which helps with sustainability,” she said.

YouthBuild programs across the nation look to community- and faith-based nonprofits for support and must seek funding from a variety of private and public sources.

Also, students face a revamped GED exam this year, with a new focus on strategic thinking, analysis and problem solving. The test is more difficult, Beckles-Thomas said, and she predicted fewer students would pass.

“You need to make sure there’s lots of preparation” when you introduce changes in tests, she said.

To Harrington, the ongoing challenge is keeping the students engaged.

Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild offers participants a stipend — a maximum of $325 per week if they meet guidelines such as full attendance and being on time.

Part of the community

In addition to directly teaching skills, the program involves students in their community. Fulton-Atlanta YouthBuild collaborates with a number of organizations. For example, Meals on Wheels, the program that delivers meals to the elderly, apprises YouthBuild of older people who need house repairs.

Harrington took his students to help a woman whose house had a rotten wooden deck. “She couldn’t get out of the door,” said Harrington. “The students learned everything about how to build a deck.”

The homeowner was grateful.

They also worked closely with Habitat for Humanity to build a new house in one of Atlanta’s low-income neighborhoods. Habitat provided the materials, and YouthBuild brought students to the construction site daily. “It’s a great opportunity for students to learn,” Harrington said.

Even the initial student construction project benefits the community, since the doghouses are all donated to Fulton County’s animal shelter.

The southwest Atlanta house that students were repairing last October will become the office of another nonprofit, Greening Youth Foundation. YouthBuild’s young adults worked alongside their peers at Greening Youth and a bevy of volunteers from UPS who were cleaning up the grounds.

Inside the house, two students cut plywood panels that Rhodes and others attached to the wall. Cinnestria Taylor stood outside to talk.

“I got in YouthBuild because I didn’t finish high school,” said Taylor. “I wasn’t good at math.” The program taught her to communicate, she said, and she has just landed a full-time administrative assistant job that will help support her and her four children.

In the future, she hopes to go to Georgia Perimeter College to study neonatal nursing.