Boys & Girls Club of Door County

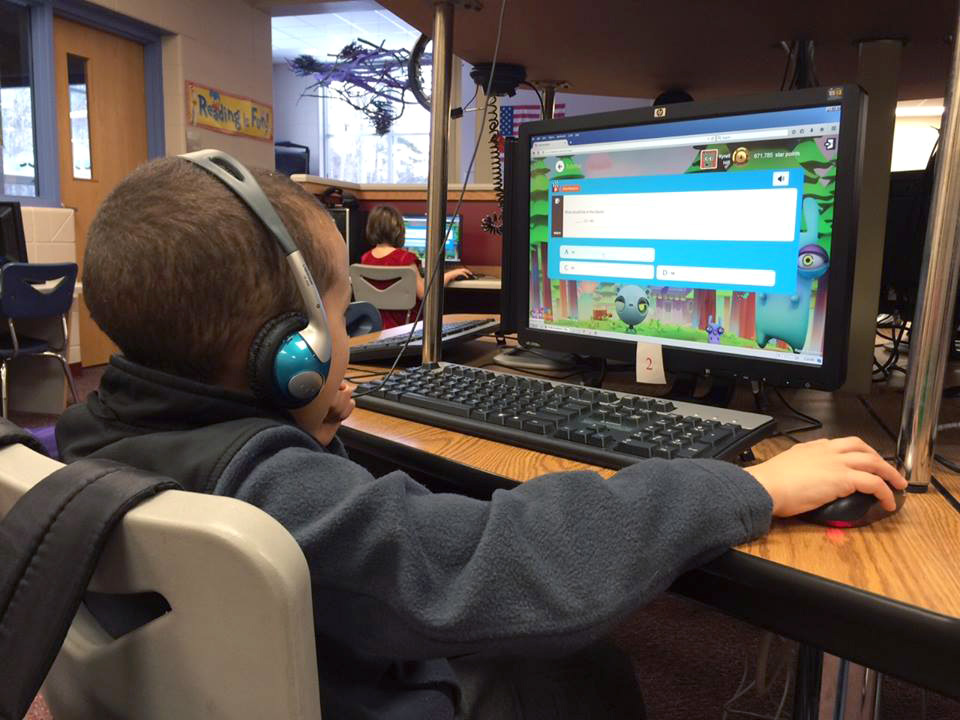

After-school programs funded by the 21st Century Community Learning Centers help kids master academic skills. A student in the Boys & Girls Club of Door County,Wis., plays math and literacy games on the web-based program Stride Academy.

Today it’s sitting precariously on the chopping block, but the federal grant program known as 21st Century Community Learning Centers once seemed like a fixture.

Born in the mid-1990s, the program provided funds to inner-city and rural schools and their community partners for after-school, weekend and summer programs.

The program grew by leaps and bounds until it supported 11,040 centers and 1.6 million children across the country with funding of $1.1 billion by 2014, according to the Department of Education.

Local partnerships grew to involve schools, churches, city and county agencies and organizations like the Y and Boys & Girls Clubs. Partners provided additional funding, with each one bringing an average of $67,000 in 2010, according to Expanding Minds and Opportunities, an advocacy group for out-of-school time education.

“It’s unique for a federal program to leverage community resources” like this, said Gwynn Hughes, a program officer at the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, which has supported the 21st Century program since its inception.

Legislation now in Congress threatens to cut the federal program and shift its funding to state block grants.

In fact, the bill in the House of Representatives, the Student Success Act, would cut 65 programs administered through the Department of Education considered to be “ineffective, duplicative, and unnecessary,” according to a statement by its sponsors, Reps. John Kline, R-Minn., and Todd Rokita, R-Ind.

A Senate committee is working on the similar Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

How after-school became a national issue

When federal funding for after-school programs was first envisioned, the idea enjoyed wide support.

In 1994, Republicans introduced legislation in Congress to “open up schools for broader use by their communities.” In the Senate, Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, and Jim Jefford, R-Vt., were sponsors.

Some philanthropists strongly encouraged the effort. In 1998, the Mott Foundation committed funds for training and assistance, and federal funding expanded to $200 million.

The goal was to put after-school care within the reach of any community that wanted to create community-school partnerships to benefit low-income kids, according to the Mott Foundation.

Before the 1990s, the after-school programs that existed had been provided by community organizations. But labor force changes between 1960 and 1990 created a new concern. The number of women working outside the home jumped more than 50 percent in that time, according to the Department of Labor. The number of children left at home unsupervised became an issue.

Changes to welfare programs also required welfare recipients, many of whom had children, to get jobs or job training.

Boys & Girls Club of Door County

Participation in the Boys & Girls Club of Door County, a program funded by a grant through the 21st Century Community Learning Centers, has grown from 60 or so children five years ago to more than 400 today.

In addition, growing research pointed to the value of a positive youth development approach, according to Sarah Fierberg Phillips, writing in the journal Afterschool Matters in 2010. Scholarship about young people had shifted from a “problem” approach, in which youth programs existed to deal with issues such as substance abuse and delinquency, she wrote. Instead, positive youth development stressed the value of building on young people’s strengths. Programs provided positive experiences and supports that helped youth develop the characteristics that made them healthy and strong.

By 2001, funding for the 21st Century program had grown to $846 million and programs were operating in 6,600 schools, according to the Department of Education.

“The goal of high-quality programs is to offer low-income students the kinds of opportunities that are available mainly to middle- and upper-class children,” wrote William S. White, CEO of the Mott Foundation, looking back in 2011.

After a report commissioned by the Department of Education raised questions about the effectiveness of these after-school programs, President George W. Bush sought to reduce funding in 2003.

But many groups still had faith in the program and challenged the Mathematica Policy Research report. An advocacy group, the Afterschool Alliance, was established with support from the Department of Education, Mott Foundation, J.C. Penney Co., Open Society Institute, the Entertainment Industry Foundation and the Creative Artists Agency Foundation.

In 2008 the Harvard Family Research Project summarized 10 years of research and concluded that children reaped a host of benefits from participation from well-run after-school programs.

Changes in the program

Some changes to the program’s focus have occurred over the years. The original idea was to use schools as community learning centers benefiting the whole community. No Child Left Behind shifted the focus to supporting children’s academic performance. In 2011, a waiver allowed states to use 21st Century funds for an extended school day.

Now the program has become caught up in the movement to shift control of education back to states and in efforts to change the testing and accountability requirements of No Child Left Behind.

“The Student Success Act reduces the federal footprint and restores control of the classroom to parents and state and local education leaders,” Rokita said in a statement when the bill was introduced in February.

The measure, which is a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in the House, is also aimed at cutting out Common Core standards and strengthening private and charter schools.

Rokita seeks to do away with many Department of Education programs that he sees as intruding upon the function of states.

Providing opportunity to communities in poverty

Julie Davis, executive director of Boys & Girls Club of Door County, Wis., is fearful of such changes.

Door County is one of the poorest counties in the state, with the seasonal tourist trade supplying a high proportion of jobs. Adults often string together two or three jobs during the seven-month tourist season, Davis said.

Five years ago, the Boys & Girls Club was created in the county seat, Sturgeon Bay, with a five-year grant from 21st Century.

“Our community did not have any kind of after-school program that concentrated on academics,” she said.

Initial funding was $80,000 for the first year, with $100,000 for each of the next four years. Initially the club drew 60 to 70 students. This year, it is serving 400, Davis said.

Fully half the elementary school children of Sturgeon Bay are club participants.

“We have changed the way our community has been looking at and caring for youth,” Davis said.

The academic side of the program focuses on skill-building rather than simply helping kids complete their homework. A certified teacher looks at the math and reading concepts children working on at school and creates lessons to build skills in those areas.

“We’re basically extending the goals and objectives of the school,” Davis said. Kids also take part in an online skill-building program, Stride Academy.

If funding through the 21st Century program were cut out, “that would be devastating to us,” she said.

Davis is adamant about the need for her program. Twenty years ago, a high school dropout could walk into a factory job, she said, but those days have gone. The current job market requires much higher academic credentials.

She sees high-quality after-school programs as crucial to preparing kids for jobs in a changed economy.

Otherwise, “what are we doing for our future workforce?” she asked.