See sidebar “Local Dance Program Gets Kids on the Move“

See sidebar “Local Dance Program Gets Kids on the Move“

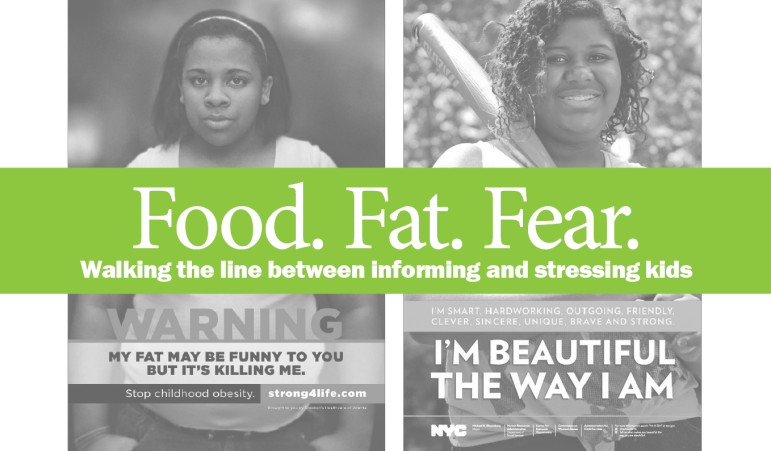

A girl with a blank expression stares out of the black and white photo. “Warning: Chubby kids may not outlive their parents,” read the words beneath her photo.

In another advertisement, a girl with a challenging expression stands with her hand on her hip: “I’m beautiful the way I am,” reads the caption.

Two ad campaigns, two approaches

The first was part of a 2011 group of ads in Atlanta in which Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta warned of the dangers of childhood obesity. The second was a series of ads in the New York City subway last year, sponsored by the NYC Girls Project, countering narrow ideas of what girls should look like.

Youth organization leaders may well wonder what approach they should take to obesity, which is considered a major public-health problem. More than one-third of kids are overweight, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC reports obesity has more than doubled in children and quadrupled in adolescents since 1980. So what’s the problem? Obesity can lead to shorter life expectancies, according to former Surgeon General Richard Camona, because it raises the risk of heart disease, cancer and diabetes.

But unhealthy dieting methods, a sense of failure, poor body image and serious eating disorders are also health concerns.

How do youth workers promote healthy bodies without contributing to the self-recrimination so many kids already feel?

Building on strengths

Girls Inc. tackles the issue without even introducing the subject of weight. Girls hear the subject all around them, said Melissa D’Andrea, director of programs at Girls Inc. New York City. So, the organization takes a more holistic approach, she said, in their in-school and after-school programs that serve about 1,500 girls ages 6 to 18. Girls Inc. New York City also reaches another 2,500 girls through workshops and partnerships with other organizations.

[module type=”aside” align=”right”]Resources

- Let’s Move! Active Schools — Offers resources for schools and after-school programs, including energizer activities and grants.

- Out of School Nutrition and Physical Activity Initiative — Developed by the Harvard School of Public Health Prevention Research Center, this site offers tips, assessments, and various guides to improve organizations’ practices and policies related to foods and physical activity.

- GoGirlGo! — A “curriculum and sports education program … to improve the health of sedentary girls” ages 5 to 18. Some materials are available in Spanish and some are for parents.

Several curricula address fitness and body image. For example, through Sporting Chance, girls plan and participate in activities ranging from baseball to kayaking to hiking. They learn that being physically fit has social and psychological benefits.

“We need to address the physical, the emotional and the media messages,” D’Andrea said. “Our goal is to focus on the whole girl.”

“One of the messages we want to put out is that healthy bodies come in all shapes and sizes,” she said. “It’s important not to come from the perspective that there is one right type of body.”

Mainstream media presents thin bodies as ideal, D’Andrea said, but girls of color might get a different message in their community, where a curvier body could be valued.

“The real problem is if you have to live up to an unrealistic ideal,” D’Andrea said. Girls examine how women are portrayed in hard news as well as in advertising. But in the Girls Inc. program, they move from just being subjects of the media to seeing themselves as creators of it as they look at careers in the media and create their own videos.

The program seeks to improve girls’ self-esteem by moving the focus from personal appearance to personal strengths.

This positive youth-development approach engages young people rather than lecturing them, and it looks at ways they can make a contribution to solving the problem.

Sports and physical activity

Out-of-school time programs can play an additional role, as schools appear to have abandoned physical education. Today, only six states require physical education in every grade, according to Let’s Move! Active Schools, a national, private collaborative supported by the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services and Education. Only one-fifth of school districts across the nation require daily recess, according to Let’s Move!

However, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends 60 minutes or more of physical activity every day for children and adolescents.

[module type=”aside” align=”right”]Rates of Obesity Among Youth According to the CDC

22.4% Hispanic youth |

20.2% Non-Hispanic black youth |

14.1% Non-Hispanic white youth |

8.6% Non-Hispanic Asian youth |

- In addition, low-income teenagers are three times more likely to be obese, according to a 2008 policy brief funded by the California Endowment. High numbers of fast-food restaurants are located in low-income neighborhoods, the report noted, while there are fewer parks and opportunities for physical activity. Sugary soda consumption is high, as is sedentary TV watching.

Source: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2011-2012 figures.

[/module]In response to research showing that girls were increasingly sedentary, in 2000, the Women Sports Foundation created GoGirlGo!, a curriculum “designed to get 1 million girls active,” said Chief Executive Officer Deborah Slaner Larkin. This free curriculum, a mix of discussion and physical activities, is aimed at girls ages 5 to 18.

The youngest girls are introduced to simple physical activities through games and imaginative play. Leaders build girls’ confidence by reading stories about diverse young girls who faced different situations. Subject matter ranges from nutrition to dealing with feelings.

Eight- to 10-year-olds hear stories about female athletes. They learn to measure their pulse and distinguish levels of physical activity from low to strenuous.

The 11- to 13-year-olds read about role models and then discuss the stories. Subjects range from body image and stress management to sex and dating.

All ages do a variety of exercises and physical activities. A crucial message is that physical activity helps girls feel good about themselves, and each lesson includes information about healthy snacks.

The curriculum has been used by nearly 1 million girls nationwide, according to the Women Sports Foundation.

In October, the foundation launched Sports4Life, which provides funding for physical activities at youth organizations serving mainly 11- to 18-year-old African-American and Hispanic girls, who are particularly at risk for being overweight, according to the CDC.

“All the research shows that participating in sports helps body image without ever talking about it,” Larkin said. In addition, sports provides a whole social network for kids, she said.

Engage kids to identify wider issues

Christine T. Bozlak, assistant professor at the University at Albany School of Public Health, State University of New York, would like to see youth programs go a step further.

As part of her dissertation research in 2010, she worked with kids ages 9 to 11 in an after-school program outside Chicago. She gave them cameras and asked them to take photos of what wellness meant to them — and also what it didn’t mean to them.

In the process, they identified changes they wanted in their school, their after-school program and the larger community, she said.

One girl took a photo of a tree. She wanted to be able to relax outside under a tree and read a book. Kids said they wished there were fewer buildings in their neighborhood and more grass to play on. They wanted less litter on the streets to make the area more inviting for play.

They noted the lack of healthy food in vending machines and a basketball court that wasn’t available because it was dominated by older kids. They asked to be able to access the school gym after school hours.

Together, these young people noted some of the factors that the CDC lists as contributing to obesity, including a lack of safe, appealing places to play and a prevalence of sugary drinks and junk food.

“Youth have a lot of the answers if we only take the time to ask them,” Bozlak said. “They are the people experiencing the situation.”

She said there are a variety of ways to engage them: writing, drawing, painting, taking photos, for example.

“It’s important to engage them in ways that are fun and developmentally appropriate,” Bozlak said.

The focus on the community is important, she said. It’s an ecological approach that looks at the varied environments an individual is in — home, school, after-school program, neighborhood, city — to see how each one impacts health.

Youth organizations have a role to play in this public health issue. They can engage kids in discussions, help them analyze the issues and build on their strengths.

Sports and recreation programs can expand to reach more kids. After-school programs can incorporate more physical activity, use creative expression to help youth identify issues and ideas, and offer a well-balanced approach to after-school meal programs. And instead of seeing obesity as an individual problem, youth leaders can take an ecological approach, and alongside kids, work to address the broader social problem.

See sidebar “Local Dance Program Gets Kids on the Move“