Photos by Stell Simonton

Listening is a skill taught in social- and emotional-education programs. Here, Michelle Jones, a group leader in the Wings for Kids after-school program at Heritage Elementary School, a Title 1 school in metro Atlanta, listens to second-grader Rasul Diagne as he does homework.

Don’t miss additional resources below the story.

Ginny Deerin walked out of a psychologist’s office one day in 1995, wrapped in thought.

It had been a difficult year. She had faced family illness and relationship challenges, and she was questioning her role at work and in the community, although she was quite successful as development director of the Hollings Cancer Center for the Medical University of South Carolina.

In counseling, she learned ways to better communicate, to listen and to be empathetic. These tools were so helpful, she was stunned she hadn’t been introduced to them sooner.

“Why didn’t anyone teach me this when I was young?” she wondered.

It was the same year Daniel Goleman’s book “Emotional Intelligence” was published, and the book hit Deerin like a thunderclap. It argued the importance of recognizing and managing emotions, and bringing this emotional knowledge to relationships with others.

After reading the book, Deerin sketched out ideas to teach kids these skills. She founded Wings for Kids, a Charleston, S.C., after-school program that has since expanded into Georgia and North Carolina, serving more than 1,200 elementary school kids. It focuses on social and emotional skills such as recognizing and managing one’s emotions, empathizing with others and developing healthy relationships — and is one of the few U.S. after-school programs using SEL curricula with low-income kids, according to the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL).

“I realized there was a set of really important skills that I had never learned — and, boy, would I have lived my life differently if I didn’t have to wait until my 40s to learn them,” Deerin said.

Interest in social and emotional education has grown so much, the National AfterSchool Association cites it among top trends in the after-school field.

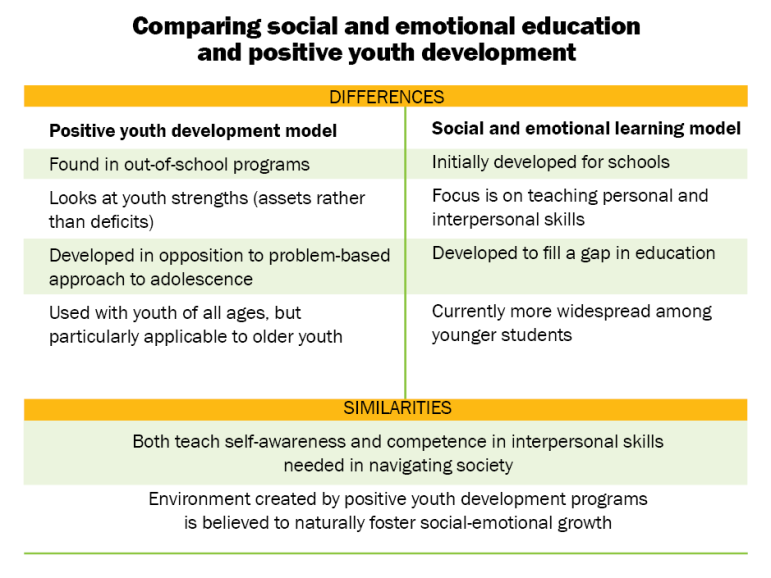

But how does social and emotional learning fit with other out-of-school program models, particularly the widely used positive youth development approach?

Emotions, relationships, choices

A major advocate of social and emotional education is the nonprofit CASEL, whose founders include author Goleman. CASEL prioritizes five general areas: awareness of emotions, the regulation of emotions and behavior, empathy, relationship skills (including communication and negotiating conflict) and responsible decision-making.

In the Wings for Kids curriculum, each day is devoted to a skill within one of the five categories. The teachers, AmeriCorps volunteers known as Wings Leaders, weave the daily lesson into each activity. Each leader works with the same group of 10 to 12 children, called a “nest,” for the whole school year. A second adult, a “peace manager,” can be called upon to take a child aside who is being unruly. The children can also request to go see the peace manager.

At Heritage Elementary School in Atlanta, children in the Wings for Kids program run out on the playground for 10 minutes after the school day ends. Then they cluster in the gym for the “community unity meeting” that starts the after-school program. Each day, kids are invited to stand up in front of the entire group to acknowledge something praiseworthy that another student or adult has done. They also recite the Wings for Kids creed and learn the daily lesson.

On one particular day, the lesson was to identify how different emotions are displayed in the body. During small-group discussions, a kindergarten teacher read a book “The Way I Feel.”

“Show me your sad face!” she told the children. “Show me your angry face.”

A fifth-grade leader played music, and the kids discussed how it made them feel and how their bodies reacted. All people don’t feel emotions the same way, the teacher told them.

The Wings for Kids program is structured to provide information in a sequenced and explicit way, built around the five areas of social and emotional competence listed by CASEL (see below) and broken down into 30 learning objectives.

Engagement, mastery, choices

In contrast, the positive youth development approach, which became widespread over the past several decades, does not involve a set curriculum. Positive youth development focuses on advancing a sense of mastery in something a young person considers important, said Dale Blyth, extension professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Minnesota.

The young person chooses what he or she is going to pursue. “That element of choice is a key aspect,” he said.

“It’s about engaging the young person rather than teaching the young person,” Blyth said.

A positive youth development program involves a commitment to the whole child, to his or her emotional and social well-being, as well as ability to be in the community, Blyth explained.

Civic contributions through volunteer work or other activities are often elements of these youth programs.

4-H

4-H clubs engage kids in projects that let them master new skills as they work alongside others — a positive youth development approach. Here, two teens work with an adult in Kittson County, Minn., 4-H to build aquatic robots to collect samples and test water quality.

4-H clubs, for example, fit this model. The programs are voluntary and kids can pick from a variety of activities.

A good 4-H program starts with young people’s interest, Blyth said. It helps them identify something they want to work on. As they pursue a project, they set goals. Older kids connect with younger ones and show them the way.

In 4-H demonstrations, kids get up and talk about their projects at a club, a fair or another public setting. They gain leadership skills as they work with adults and youth of different ages.

There’s less formal teaching and more experiential learning.

“Those ways of being, relating and doing come about when you give young people real-life experiences,” Blyth said.

Many other out-of-school-time programs make use of the positive youth development model. For example, the Clarkston Community Center, based in an Atlanta suburb with a large immigrant population, brought together about 50 teenagers to discuss issues of interest to them. In a facilitated discussion, they pinpointed a particular concern: police profiling of youth of color. They organized a group, the Clarkston Youth Initiative, to take on various projects, including sending a delegation to meet with the local police chief.

Where the two approaches meet

Positive youth development starts with a young person’s strengths and builds on them, said Karen Pittman, co-founder, president and CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment.

A good youth-development program sets up an environment in which social and emotional skills are naturally acquired and practiced, Pittman said.

A quality learning environment has to be safe, structured and engaging, drawing kids into the content and into relationships with other people, Pittman said. It has to provide opportunities for skill-building and choice.

“If you’re in an environment that has those characteristics, you’re more likely to be engaged in learning,” and you are simultaneously practicing social and emotional skills, Pittman said.

Blyth agrees. Social and emotional skills, attitudes and behaviors are both “caught and taught,” he said. They can be taught in a formal curriculum, and they can be caught in environment where you see them in action.

Hank Resnick, a senior advisor to CASEL, also agrees. Social and emotional learning has “a lot of overlap with positive youth development,” he said.

It also encompasses a number of other efforts and initiatives: the “whole child” model, service learning, school climate initiatives and college and career preparation, among others.

“The long-term goal is to prepare young people to live better and more productive lives,” he said.

Stell Simonton

Kindergarten girls (from left) Ja’niya Taylor, Amber WIlliams and Olivia Pullen make happy faces as the leader of their Wings for Kids group reads the book “The Way I Feel.” The lesson for the day was about how specific emotions feel in the body.

Grant dollars for both

Resnick sees the U.S. Department of Education’s $23 million School Climate Transformation Grant, which seeks to improve behavior outcomes and learning conditions for students, focusing on supportive environments needed to foster positive behavior, as an indicator of a growing commitment to social and emotional learning.

In addition, significant private funders are interested in the approach. For example, CASEL has major support from the Novo Foundation, the Einhorn Family Charitable Trust and the Austin, Texas-based 1440 Foundation. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Noyce Foundation and the Spencer Foundation are also funders of CASEL.

In addition, the Susan Crown Exchange has thrown its weight behind social and emotional education, exploring best practices in partnership with programs around the country.

Social and emotional education also has a friend in the Edutopia foundation, begun by George Lucas, which has been advocating it for a decade.

Moving beyond school

CASEL is very school-focused, Resnick said. Schools have a responsibility to teach the kinds of skills that young people need to succeed, he said.

However, some funders and business leaders are seeing out-of-school programs as an ideal place to develop important skills in young people, Pittman said.

They’re concerned about getting young people prepared for future jobs, and they’re asking what are good ways to prepare them in the areas of science, technology, engineering and math, she said.

“They’re recognizing that often the way the content is taught in schools doesn’t reinforce the building and practicing of those teamwork, problem-solving, time management, self-regulation, curiosity and learning-from-failure skills.”

After-school programs that address social and emotional learning — and those that work in a positive youth development model — can be a crucial link in preparing kids for the future.

Five categories of social and emotional skills:

- Self-awareness: The ability to accurately recognize one’s emotions and thoughts and their influence on behavior. This includes accurately assessing one’s strengths and limitations and possessing a well-grounded sense of confidence and optimism.

- Self-management: The ability to regulate one’s emotions, thoughts and behaviors effectively in different situations. This includes managing stress, controlling impulses, motivating oneself, and setting and working toward achieving personal and academic goals.

- Social awareness: The ability to take the perspective of and empathize with others from diverse backgrounds and cultures, to understand social and ethical norms for behavior, and to recognize family, school, and community resources and supports.

- Relationship skills: The ability to establish and maintain healthy and rewarding relationships with diverse individuals and groups. This includes communicating clearly, listening actively, cooperating, resisting inappropriate social pressure, negotiating conflict constructively, and seeking and offering help when needed.

- Responsible decision-making: The ability to make constructive and respectful choices about personal behavior and social interactions based on consideration of ethical standards, safety concerns, social norms, the realistic evaluation of consequences of various actions, and the well-being of self and others.

Source: Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

Additional Resources

- The Center for Youth Development (extension.umn.edu/youth/) at the University of Minnesota carries out research and is a resource on positive youth development and social and emotional learning. It sponsors 4-H, one of the largest youth development programs in the United States, and also has an informative blog.

- Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (casel.org) is a leading resource on evidence-based social and emotional learning.

- The Forum for Youth Investment (forumfyi.org) promotes positive youth development through policy and partnerships.

- Search Institute (search-institute.org) has promoted a positive approach to youth development for 50 years.

- Susan Crown Exchange (scefdn.org) seeks to invest in social and emotional education to help youth adapt and thrive.