SPRING VALLEY, N.Y. — On the evening of April 23, the members of the the East Ramapo Central School District’s board passed, with a unanimous vote and a barely audible mumble of approval, next year’s budget. Frustrated parents shook their heads, with weary looks of resignation. “What about the private school cuts,” one woman shouted from the audience. One fact obvious to anyone who was there or who is familiar with politics in the western edge of Rockland County, just north of New York City in the Lower Hudson Valley is that the parents were all black and Latino and all but one of the members of the board were white, Orthodox Jewish men.

Nearly everyone in attendance agreed, the budget, even this one that included a fresh round of deep cuts to an already decimated system, was likely going to need fresh hacking by summer’s end. A significant chunk of this provisional budget was predicated on longshot money the board hopes to get from the statehouse in Albany. But no one realistically thinks these funds are coming, especially for a town whose mayor is consumed in a statewide corruption scandal and named in a federal indictment. That means fewer teachers, more overburdened administrators, less security, and the elimination of more sports, programs and a wide array of electives and clubs that the students praise.

Nearly everyone in attendance agreed, the budget, even this one that included a fresh round of deep cuts to an already decimated system, was likely going to need fresh hacking by summer’s end. A significant chunk of this provisional budget was predicated on longshot money the board hopes to get from the statehouse in Albany. But no one realistically thinks these funds are coming, especially for a town whose mayor is consumed in a statewide corruption scandal and named in a federal indictment. That means fewer teachers, more overburdened administrators, less security, and the elimination of more sports, programs and a wide array of electives and clubs that the students praise.

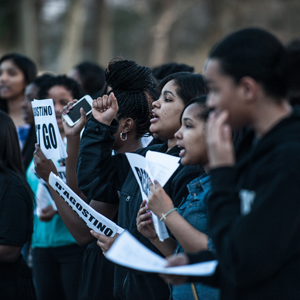

April’s board meeting lacked much of the theater and civic fireworks that have distinguished recent meetings; the protests, the accusations of anti-Semitism, the symbolic show of the board members recusing themselves to the executive suite to outlast angry parents and students delivering fiery speeches to empty chairs. But it did retain one distinctive feature — the furtive, almost clandestine way people talk to one another after the meeting has been gaveled.

Some audience members gathered in small, tight circles in the back of the board room. Others slipped into the hallway and began to talk in hushed tones.Two words whispered like a warning in the hallway that evening were those of a Brooklyn neighborhood.

“Crown Heights,” said Robert Forrest, casting a glance down the corridor.

Many worry that a perfect storm is brewing for a public safety catastrophe.

“That’s what’s going to happen here. I’m surprised it hasn’t happened yet, honestly. This is little East Ramapo, not Brooklyn, not New York City. We don’t want that happening here. But if we keep taking everything from these kids that’s what we’re going to get. We’re waiting for Armageddon.”

Like many here active in the fight between those involved in the public schools and the religiously-dominated school board, Forrest, a candidate running in the May 21 school board election, said he does not wish for the violence. But when he looks at the cuts the school board has made — a board of Orthodox Jews who do not mirror the demographics of the children they serve (a mostly black and Latino school district) — he is one among many who worry that a perfect storm is brewing for a public safety catastrophe.

Ramapo, like most school districts in New York, is under tremendous financial strain. Aid has been cut and state and local governments are hamstrung by a 2 percent tax cap implemented by Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2011. But Ramapo’s problems are also unique in the state. Here, a complicated set of circumstances brought about by a demographic split has allowed public money to pour into religious schools. In this community in the Lower Hudson Valley, some 21,000 private school students are from the Ultra Orthodox community, more than double the number of public school children in the district.

To understand how the members of a religious sect took control of the only majority black and Latino school district in all of Rockland County, one has to be aware of local demographics, little known loopholes in the law, and the anti-modernist tradition of the Hasidic community.

Because of state and federal law, if a child needs special education and the school district can not provide it, then public money must pay for the student to attend a different school that can provide those services. In Ramapo, the public schools can provide those services. But the Hasidic community argues that since their religion forbids them from sending their children to public schools (girls and boys cannot attend the same schools, for instance, let alone ride in the same school buses), the local the school board needs to pick up the tab.

Leaders of the Hasidic community here have argued that before they earned a majority on the board, public school advocates were not providing them their fair share. Since the community has taken control of the board support for public schools and other services that serve public school children have been slashed. Leaders of the Hasidic community here argue that their children don’t need sports, or arts or music, so why do the public school children?

Legally, the state is only required to provide what is mandated. This includes basics such as math and writing, but does not include sports, arts, music, debate teams, science clubs, African-American studies, and a wide array of electives that focus on various professions.

In practice, providing public support only to the basics and nothing else, is virtually unheard of in the state, or in most public school districts.

Most parents, students and educators say those programs enrich education and attract students to school and, more importantly, keep them off the streets and involved in something where they are supervised. But, using the logic of austerity, the religiously-dominated board have slashed and gutted classes and programs, the last budget being only the most recent. With some students attending as many as five lunch periods or study halls per day because of a dearth of teachers, public school advocates say the cuts are getting down to the bone now.

Yehuda Weissmandl, a Haisdic Jew who assumed leadership of the school board when his predecessor abruptly resigned last month, said the allegations that the religious dominated board redirects the money from public school children to the yeshivas is false.

“The biggest misconception that we have here is that we’re sticking our hands into the pockets of the public school kids and putting it in our childrens’ pockets,” he said. “That is not true and it is offensive. I give away lot of time to these children, time I should be spending with my children because I’m very passionate about these children.”

He said the blame lies with the calculation Albany uses to determine state aid.He said 76 percent of the children in East Ramapo qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, more than double the state average. But the state, since it only counts the 9,000 public school children in its calculation, funds them as if they were one of the wealthiest.

“We’re not poor,” he said. “We are very, very poor. Unfortunately we’re in the position where nothing else is left to be cut. We’re down to the skin and bone at this point.”

This small-town clash of civilizations has been described by many as a “civil war.”

Public schools advocates counter that if the district received more state aid the members would simply redirect the additional funds to the private school children and leave the public schools in the same desperate situation they are in now. They say there is no tracking of the money that goes to the the special education teachers — many of whom are members of the Orthodox community. If Weissmandl and the other Haredi board members cared about the public schools, they wouldn’t keep the process shrouded in secrecy, and they add, the state wouldn’t have said that their circumvention of the process is illegal. A few years ago the board fired the district’s lawyer and retained a high-powered firm that specializes in navigating this unusual situation and sued the state for challenging its process. Later, the district sued the state for challenging its process and is spending at least $1.5 million to have the firm pursue the case with district funds.

Last week a federal judge made a significant ruling in a case brought by more than 300 public school parents who claim the board has raided millions of dollars of public money and funneled it to private schools in their community.

An Uncertain Present Haunted by a Violent Past

Crown Heights, a now rapidly gentrifying enclave in central Brooklyn, is a neighborhood whose name became code for ethnic, racial and religious strife in New York City. In August 1991, riots broke out in the streets of Crown Heights when a Guyanese boy Gavin Cato, 7, was killed after an accident involving the motorcade of a Hasidic Rebbe. The accident, the boy’s death, and long simmering tensions between the Caribbean and Hasidic communities precipitated in three days of violence, beatings, looting and destruction. An Israeli flag was burned, Hasidic homes were damaged, and hundreds were injured. Yankel Rosenbaum, a Hasidic man, was stabbed and beaten to death by a group of black men.

What people fear here is Crown Heights with a twist. They worry that the teenagers in the public school system, after witnessing their social safety net slashed by a religiously-dominated majority on the school board, will turn to violence as a solution to the problems for which the intractable racially and religiously tainted politics here has had no answer.

This small-town clash of civilizations has been described by many as a “civil war,” one where the black and Latino students are the victims. The clash has created an emergency that politicians, advocates, students and their parents worry is imminent. They say that as the board continues to cut the resources for public school children it is creating the conditions for a school-to-prison pipeline, where children and teens without a network of programs, nothing to do, and no one to supervise them, will turn to the streets for answers. Driven out of the school system, they will be funneled into the criminal justice system.

“That’s a huge concern for us,” said Spring Valley Police Chief Paul Modica.“My biggest fear is that they’ll cut all these programs and the kids will have nothing. We’re a village of working class families. These parents they’re working two, three jobs to make ends meet. You’re going to have a situation where these kids are going to have nothing better to do than roam the streets.”

Spring Valley is one of 17 police jurisdictions in the state that is responsible for 80 percent of the violent crime that occurs outside of New York City. Most of the children affected by the cuts live in Spring Valley, Modica said.

He says his department stays busy, despite being understaffed. He recently hired 11 officers to bring the total to 58. Among them he has one detective with juvenile training. Modica, a father of four, said his concern began when he took over as chief in 2007 and the first of the cuts were made. Most of the children hurt by the cuts, he said, live in his district. Now, with the remaining programs to be cut to “bare bones” he is worried about a public safety emergency.

“The thing of it is,” he said. “Is that everybody sees it’s happening, and it’s still happening.”

Two Sides and No One Is Listening

As of now, with the two sides incapable of even listening to one another, there is little confidence that anything can be done to avert it. A number of lawsuits — federal, state and local — are wending their way through the legal systems, and other state agency reviews of the situation are underway. Activists have appealed to the state to take emergency action and replace the school board.Those, however, are a long way off from any resolution and the emergency facing the town’s children, observers say, is urgent.

“There is no going back and reliving your childhood, you only go around once” said Ed Day, a county legislator who represents the district. “We can’t undo this. Our kids are in trouble. It’s a ticking time bomb, it really is. I don’t see color here, I see families trying to do the best they can. But there is nothing left for them. Nothing.”

Rabbi Mayer Schiller, a member of the Hasidic community, said he is keenly aware of how the relations in town have deteriorated as the battle over the school board has coarsened feelings between the Hasidic community and the other residents in the working class villages that make up Ramapo.

“There is so much fear and suspicion on both sides,” he said from the doorway of his synagogue, Rachmistrivka, housed in a multi-family dwelling that sits in a cul de sac. “The residents here, they inhabit different worlds. The challenge is to preserve our identity without denying the identity of the other. It is a real conundrum.”

Invisible Lines, Palpable Tensions

There are borders that divide the residents of Ramapo that don’t correspond to any official municipal registry. They are invisible but penetrate every part of life. There are no signs, nothing to mark the boundaries of these divisions, but they are real, and many here worry they threaten to turn a generation of children eager to pursue the American Dream into prisoners instead of graduates.

“These students, what are they going to do with their time now,” asked Olivia Castor, a Spring Valley senior and head of the East Ramapo Student Coalition, an activist organization fighting the board. “Most of them they have nothing to go to school for but study halls. It’s a chain of effects. If you are on the streets you are going to get in trouble. If you get in trouble you are going to go to jail. You go to jail you end up in the system. And if things don’t change we’re going to have a real problem on our hands. If students have nothing to do these kids are going to look for something to alleviate their boredom.”

Public Versus Private

The differences between the residents here run deeper than houses of worship, or the study of sacred texts. They are granular and work their way into every aspect of life. Haitian barber shops and Central American markets butt up against Kosher pizzerias and markets. At bus stops, clusters of Hispanic families wait for a bus while 50 yards away, Hasidic families in their conservative garb, wait for a separate bus. Even a glance at the architecture of a health clinic will reveal which residents it serves. The differences are sharp but ubiquitous.

The divisions reveal themselves even in the use of language. Residents use a shorthand of the “public kids” and the “private kids,” to demarcate the black and Latino children from the Hasidic children. There are separate newsletters filled with tips for children, one for public school parents and one for non-public school parents.

“We live two separate lives, we live in two separate worlds,” Arnold Cruz, a sophomore at Spring Valley High School, said of the Hasidic and Hispanic and black residents in Ramapo. “There’s like a boundary that divides us. It’s not official, it’s not one you’ll find on a map, but you can feel it. It’s one everyone knows.”

The community prizes insularity, and view diversity as a threat to their worldview instead of a pleasant civic buzzword.They see its teachings as anathema to the values of insularity, unwavering dedication and strict observance of ancient law, and opposition to most modernity. Hasidic children are forbidden from using the Internet, and even when they reach adulthood they use censoring filters to ensure they don’t happen upon a site that will undermine what they consider their sacred values.Many communities have bans on reading mainstream newspapers and mingling with anyone outside.

“They have to segregate themselves or else they will lose their community to modernity,” said Oscar Cohen describing the Hasidic community. Cohen is a retired school administrator and an activist working with the NAACP to fight the school board’s cuts. He says he wants to make sure public school children get all the resources he thinks they’re entitled and the quality education they deserve.

What has happened here defies the normal narrative about minorities and majorities. For about the last 15 years, Ramapo and its constituent villages have been populated by different branches of the Haredi community, the most conservative branch of Judaism, also described as Ultra Orthodox Hasidic Jews, and their 20,000 students. The community prizes insularity, and view diversity as a threat to their worldview instead of a pleasant civic buzzword.

“Whether the motivation is religious or ethnic or cultural — in truth they’re all melded together. Their sacred beliefs, their food, their customs, their devotion to rabbinical Jewish law, their clothing, suggest that separation is the only way,” Cohen said. “They can’t assimilate without losing that lifestyle. They must educate their children to achieve those sacred values. And so the yeshiva becomes the most sacred institution aside from the synagogue because it keeps their children separated, and allows them to pass those values on.”

Cohen, although a veteran of this decade-long battle with the religiously dominated public school board, said he is sympathetic with the position of the Hasids. He understands the frustration of the fast-growing Hasidic community.They have large families, taking literally God’s encouragement in Exodus to be “fruitful and multiply,” and they all attend private, religious schools. But, Cohen adds, they pay property taxes which go to fund the public schools.

“I empathize with them, why should I subsidize those children? Our children aren’t going to the schools. What difference does it make? Let’s give them as little as possible just what’s mandated by law — not one penny more. What’s mandated by law is rock bottom. That’s the nut of the problem. If I’m a Hasid and I can’t benefit from the education because I must send my kids to yeshivas, I’m completely invested in the religious school system — there’s no reason for me to give a damn about the public education system.”

Cohen said on his last visit to the district that Gov. Andrew Cuomo promised to work on finding a solution. But since then, he said, the governor’s people have not responded to his calls.

“It’s the governor and the legislatures responsibility to come up with something,” he said. “I voted for the guy,” Cohen said. “I think he’s done a lot of good things, but this is not one of them.”

The governor’s press office did not comment for this story.

Cohen said it is his “worst fear” that there is going to be an increase in the number of young people ending up in the juvenile justice system because of the deep cuts in services.

Separate and Unequal

On the other side are immigrant families and their 9,000 children who see the education system as at the heart of their aspirations to becoming part of the American fabric. This collision of worldviews, one that many on both sides say is irreconcilable, has led to a fight for political control of the local school board, and subsequently for the future of a generation of poor mostly black and Latino children here.

In January of this year the last two remaining non-Orthodox members of the board resigned in protest, citing intimidation from their fellow board members as a reason for their sudden departure. More recently, in a move that shocked many observers, board president Daniel Schwartz resigned without warning or much of an explanation, mid-way through his term. Mr. Schwartz did not return calls for comment on this article.

Instead of race driving a wedge between people, it’s religion, but with the same disastrous results.

Willie Trotman, president of the Spring Valley chapter of the NAACP, has worked with Cohen since 2002. They have worked side by side in the effort to remove the board, reform the school system, and restore the programs to the children here. But Trotman does not share his colleagues’ empathy for the Hasidic community. He sees the battle for the schools in stark, unequivocal terms.

“This is about segregation,” he said. “This about a system that is separate and becoming more and more unequal. I think it’s the Hasidic community versus the rest of the world.”

Trotman, 65, graduated from Carter-Parramore High School in Quincy, Fla., in 1964. When he attended Carter-Parramore High School he knew when he had hand-me-down textbooks because he would see the white students’ names written in the front and the marks they would make on the pages, notes they’d jot in the margins. Although his school was only 20 miles from the state capitol in Tallahassee, Trotman and his black classmates never had the opportunity to visit on a field trip, something students from the white high school would do routinely.

“I came from a place of segregation,” he said. “I don’t believe in segregation in any form.”

Trotman said he worries that what he sees happening in Ramapo is a repeat of the institutional segregation he and his black classmates suffered all those years ago. He said what is happening here in Ramapo, a small northern town is an updated version of what he endured in Quincy, a small southern town.Instead of race driving a wedge between people, it’s religion, but with what he said are the same disastrous results.

“If you want to put your kids in a private school fine, but we fight for public education because of Brown versus the Board of Education,” he said. “They’re unjust to their kids by not allowing them to become part of America. You just can’t become part of Monsey,” he said referring to the mostly Hasidic village, “and not part of America and then expect America to pay for that. That diversity is what America thrives on.”

The Student

Arnold Cruz’s memories of his hometown are fuzzy, and growing more vague as he gets older. He left Guatemala City when he was still a child. He remembers playing with his grandparents and the sounds of construction on a new house, but not much else. His mother secured a working visa when Cruz was three and she moved to Spring Valley. Cruz said she came, like many Central American immigrants, for better economic opportunity, but also for an education for him.He said there are a lot of barriers to an education for someone like him back home.

Cruz said the school board, what he described as a takeover of the school board by Ultra Orthodox Jews, has destroyed his mother’s dream for him.

Cruz, an only child, lives with his parents in a small but well-kept, one-bedroom basement apartment on South Madison Avenue, not far from the East Ramapo District offices. His mother is a housekeeper for a Hasidic family in the neighboring village of Monsey. His father worked the deli counter at a nearby bodega in Nanuet, but he lost his job when the store made cutbacks.

On a recent Sunday afternoon he was walking to his church, Fraternidad Cristiana Church, housed in the first floor of a low slung strip mall building next to a Dunkin Donuts. He bobbed his head to raucous heavy metal called “I Am Bullet Proof” by the Black Veil Brides on his phone, carrying a Spanish Bible under his arm. He was wearing a T-Shirt that read: Epic Fail.

“I want to have the American Dream that my parents couldn’t have. But I don’t know if I’ll have that now.”

Now, Cruz, a 15-year old sophomore at Spring Valley High School, said he is worried that his mother’s efforts to secure that education for him are imperiled. Cruz, a guitarist in a rock band called Parallel to Perfection, has seen the school board enact deep cuts to the music department, with more likely to come. The cuts have also cut programs for job training that Cruz wanted to take to prepare for studying engineering.

“You know besides the language I speak at home and the food I eat,” he said as he motioned to a bag of Quesitos he was snacking on, “I am an all-American kid. I want to go to a good school. I want to go to college. I want to have the American Dream that my parents couldn’t have. But I don’t know if I’ll have that now. Not here. With these budget cuts we’re going to have to leave.”

Part of the frustration of Cruz and other Latino residents is that they have not had the opportunity to influence who is elected to the board because they cannot vote. That has doubled the frustration for the immigrant community here who feel like they have no control of their democratic fate.

“What I feel like is that the politicians don’t treat us as equals. It’s frustrating. If my mom could vote she would’ve voted against the budget cuts because she cares about my future. It really gets me angry,” Cruz said. “The people from the Spanish culture — the mothers and fathers, the grandparents — they would’ve all voted to keep our programs. It’s what our world revolves around.”

He is not alone in his frustration and mounting anger. That sentiment of helplessness and resentment was echoed among both parents and children after the service at his church.

‘Why are they doing this?’

Pastor Henry Vega, 32, stood in the glare of the fluorescent lights while parishioners bustled around him stacking chairs and putting away tables after the service. Some volunteers handed out steaming styrofoam plates of homemade chicken tamales. His 18-month old son, Samuel, kept tugging on his slacks, in a playful attempt to get his father’s attention. Older children squealed as they scampered by him in a game of chase. As he spoke, his face turned from a ebullient smile to a stern grimace.

“The parents,” he said in Spanish. “When they realized what was going on in the schools, they were angry. They came to me asking, ‘why are they doing this?’ I feel frustrated. The schools are fundamental to a good life. You are pushing them and pushing them to go to school, to do well in school. And then they go to the schools and they’re no good. There’s nothing there for them. What do I tell them now?”

He said the cuts to kindergarten and after-school programs have been particularly hard on his congregants, most of whom are working parents who have had to scramble to find child care while they are at work.

“We have immigrants here but we have a lot of people who are citizens in the church. They have to vote — you have to lift up your voice. That’s how our values are going to be heard. The only way we can change this is lift up our voices and say, ‘We’re here!’”

‘It’s about to happen’

Jorge Ambrocio, a youth pastor at the church, runs a program called Generacion de Fuego — the Generation of Fire — to fill in the gaps left by budget cuts in the school district. He said he goes out into the streets and tries to convince them to come to their meetings on Friday nights. He works with a lot of kids from the sister high schools in the district, Spring Valley and Ramapo, he said, and many have told him that they don’t even bother going to school anymore because there’s nothing there for them.

Ambrocio, 30, pulls out a photograph of what he was like when he was young and stalking the streets himself. He does not want the same for Cruz’s generation.

“It’s sad to see that some of these kids might never finish high school,” he said.“We encourage them to go back to school. But what is there for them to go back to?”

Katrina Hertzberg, who runs the afterschool program in the East Ramapo school district, said she doesn’t know how many children she has saved from the streets in the years she’s been in charge. But she is certain she has already lost many since the board started asking for rent. She said many of the children she worked with were already in crisis.

“These kids are already in the school-to-prison pipeline,” she said. “It was a problem before these cuts. So what is it going to be now?”

“There are many, many kids who used to be in our program and the parents can’t pay for it anymore,” she said. “And the reality is we’ll be closed in a year or two. And it’s not because we want to stop doing what we do. It’s not because we suddenly don’t love these kids anymore. It’s just that we literally can’t do it anymore. Our budget is going to be way over.”

Hertzberg, echoing the grave concerns of many in town, said she fears the worst.

“It’s shocking to me that there hasn’t been violence here already,” she said.“Young men from the public school community, young men from the non-public, Hasidic community — Pow!” she says, smashing her fists together. “It’s about to happen.”

Two years ago Modica, the police chief, started a program to help head off the disaster he fears is coming. Named the Youth Police Initiative, the program brings children aged 9 to 18 who he says are “heading down the wrong path” and has them work with police officers on team building.

“We’re trying to make that connection between the kids and the officers,” he said. “When they’re on the street I want them to think, ‘I have a good relationship with Officer X, let me reach out to him before I make this bad decision.’”

At the completion of the two-week program officers hand out certificates. Last year one of the children participating got his certificate on his 10th birthday.The officers chipped in and got him a birthday present.

“He had never gotten a birthday present before,” he said. “He was crying. The father was crying. I was crying. The officers were crying. The cops can forget that these are just kids growing up in a rough area.”

Modica says the program is a success but it can only do so much, and fears what even deeper cuts mean for the stability of his village.

‘They’re the same amount of American’

Rashelly Palma should have been in a class on a recent Tuesday afternoon. It was just after 1 p.m., but instead of sitting in class she was working in her family’s store, a curiosity shop that features an eclectic collection, everything from Christian-themed gifts and DVDs, books including the Bible, to a variety of sundries and cosmetics. She was arranging items on a shelf.

“I had nothing else to do in my 8th period so I came here instead,” she said.“But I’m lucky. Not everyone has a job to go to like I do.”

Palma is not alone. It has become a fixture at the rallies and meetings by the public school advocates to hand out copies of students’ schedules that feature as many as five lunch periods and study halls. It is a consequence of the deep cuts the school has endured, and there are more coming.

Palma, a 17-year-old senior at Spring Valley High School, said she hopes to be a chef or baker when she finishes school. But elective courses like culinary arts have been curtailed in addition to Advanced Placement classes and other courses students say give them an edge when applying for college. That’s why she was rearranging tchotchkes instead of taking notes, she said.

“What about me,” she asked. “The people who don’t want to pursue careers in the maths and sciences? What am I supposed to do?”

Elsa Palma, Rashelly’s mother, like many of the parents in Spring Valley wants what’s best for her children.

She said many parents here are working two or three jobs to survive. They mean well, but they all can’t be on top of their children the way she is. She worries with parents distracted by work, counselors laid off, after-school and clubs nearly wiped out, that it’s just a brute reality that there will be children out on the street with nothing to do.

“Their kids, the private kids, and our kids, they’re the same amount of American, you know,” said Elsa Palma, in Spanish from behind a glass counter filled with cosmetics. “We’re in America. Everyone deserves a chance.”

She says the two communities need to come together, but in recent years the tension has grown and the resentment has started to harden. Attempts to mediate the two sides have ended with failure. Now communication between the two sides is limited to angry exchanges at the public meetings and little else.

‘A Porous Wall’

On the afternoon of April 13, the parking lot of Gracepoint Gospel Fellowship, an evangelical megachurch just off Interstate 87 a few miles from Spring Valley, was filling up. Inside, crowds gathered in the wide lobby. But on this particular Saturday afternoon, the crowds were not drawn here to talk about salvation.The church was hosting a forum on how to save the schools instead of souls.

Clusters of people talked passionately next to “Sacred Grounds,” the in-house coffee shop and bookstore. Booths with coffee mugs of pens and clipboards encouraged people to sign petitions.

Among the hundreds of visitors to the church that day were a slate of local politicians there to deliver their well-rehearsed talking points on the crisis in the public schools. They were joined by public school activists, attorneys and parents.

Members of the school board were not invited. Even if they were, Saturday is Shabbat for Ultra Orthodox, so they would not have been able to attend.

Rabbi Schiller said the debate about the future of education in Ramapo is made even more complicated by how religion has seeped into the conversation.

“The wall between church and state …” he said, “the more you look at it here the more you see it is a very porous wall.”

The speakers took turns on the stage in the spacious auditorium while parents and concerned residents sat in the stadium seating. An array of lights mounted above cast a theatrical light on the podium, flanked by two massive screens that flashed the words “May 21st Vote!” an advertisement for the next school board election. Although ostensibly a political event, the forum took on the color and cadence of a religious service. A pastor delivered a prayer dedicated to the “little ones” to start the event. There was a call-and-response encouraging people to vote.

A few days after the event some teens, the sons of Haitian immigrants, were hanging out on a corner of Maine Street in Spring Valley. Talk eventually turned to history, recent and distant. And that prompted some boasting about their post-racial feelings. Across the road a mural painted on the side of the cultural center shows Haitian soldiers fighting against their French master, while the phantom of George Washington looked on, giving a magical realist imprimatur on the slaves fight for freedom.

The painting is a warped conflation of history and the American aspirations many immigrants feel so deeply here. In reality President Washington responded to the rebellion by supporting the white government. But many want to believe that the American story is their story, too.

The teens, dressed in hip coats adorned with ironic pins, did not know why exactly they had seen their high school turned into the equivalent of an educational ghost town. The political machinations, they said, were beyond them. They disagreed about how things had turned so desperate. Some blamed themselves for their apathy as well as infighting in their community. But there was no question in their minds that what was happening was unfair and needed to change; and they agreed about what would happen if it didn’t.

“Our schools are barren,” said Ricardo Laguerre, who graduated from Spring Valley High School last year. “There’s nothing left for us. We all know what’s going to happen,” he said motioning to a Hasidic man walking along the sidewalk. “Idle hands. You have nothing to do. You know the saying. It’s the Devil’s Playground.”

Photos by Robert Stolarik