Born in Calcutta, Yves Gomes came to the United States with his Indian mother and Bangladeshi father when he was a year and a half. He made his way through the public school system in Maryland, graduating in the top 5 percent of his high school class in 2010 and landing a coveted spot at the University of Maryland’s flagship campus in College Park.

But Gomes, who is now 20, couldn’t afford to attend. As an undocumented Maryland resident, he’d have to pay out-of-state tuition, about $26,000 a year, rather than the in-state rate of about $8,000. He also had other things to worry about, like an impending deportation. His parents had already been deported, to separate countries, a few years earlier.

But Gomes, who is now 20, couldn’t afford to attend. As an undocumented Maryland resident, he’d have to pay out-of-state tuition, about $26,000 a year, rather than the in-state rate of about $8,000. He also had other things to worry about, like an impending deportation. His parents had already been deported, to separate countries, a few years earlier.

Gomes, who had stayed on with relatives to continue his education, managed to win a short-term reprieve from immigration authorities. He enrolled in community college and completed his associate’s degree, all the while longing for a chance to pursue a bachelor’s degree at the University of Maryland. This Nov. 6, he got another break.

On Election Day, 58 percent of Maryland voters gave their approval for a law known as the state’s own DREAM Act, which allows undocumented students like Gomes to pay in-state tuition rates at four-year public colleges and universities if they fulfill certain criteria. The law had been passed by both state chambers and signed by Gov. Martin O’Malley in May 2011, but a petition signed by more than 100,000 citizens shortly afterward triggered a voter referendum, known as Question 4 on the November 2012 ballot. The law was put on hold until then.

Advocates who had worked to create public support while the law was making its way through the General Assembly, now rallied to build awareness of the referendum. The key, they believed, was to dispel public misconceptions about the law as a handout to illegal immigrants. More than 21 organizations, including local chapters of the ACLU and NAACP, the state’s largest teachers union, faith groups and advocates, formed a coalition called Educating Maryland Kids, whose sole mission was to get the referendum passed.

“If you want to change people’s minds about issues that they wrestle with, you don’t do it with a flyer. It’s hard to do it with 30-second commercials,” said Alisa Glassman, lead organizer for Maryland IAF, a grassroots community coalition that also joined Educating Maryland Kids. “It happens with a face-to-face conversation usually with someone you trust, usually a neighbor or friend or pastor.”

So a year ago, Maryland IAF began to train 540 clergy and lay leaders to talk about the law in their neighborhoods, schools and churches. “Strategically, it was important for us to organize African-Americans and Africans as a way of building support in the African-American community,” Glassman said.

The measure was “just common sense,” they told people over and over: families who had paid Maryland taxes for years and students who had studied for years at and graduated from Maryland schools should be given the chance to receive Maryland rates for college tuition. Students had to complete 60 credits at a local community college before they qualified for in-state tuition to a four-year school, and they could not receive any government financial aid, they explained.

Another key strategy was showing the public that students from a diverse range of backgrounds were unable to access educational resources because they were undocumented. It wasn’t just an issue that affected Latino immigrants, but African, Asian and European immigrants too.

“People said, ‘I thought only Latinos were involved with it.’ It was very shocking for them,” said Yannick Diouf, a community college student from Senegal who spoke at churches and other places of worship about the legislation. “I think that it broke people’s misconceptions more than anything, because they had a certain image of what that person is supposed to look like. It certainly helped make our point: that this is a huge problem and not just one demographic of people.”

Gomes agreed. “This is not just an issue that affects the Latino community but all immigrant communities,” he said.

Brad Botwin, founder and director of Help Save Maryland, a nonprofit that helped gather signatures against the Maryland DREAM Act, thinks such an approach to shoring up support ignores the financial realities for the state. He campaigned for a No vote on Question 4.

“The arguments on the other side were, ‘These poor kids.’ And that really was it,” Botwin said. “There should be no reward for breaking the law.”

Botwin thinks DREAM supporters will now begin lobbying for undocumented students to receive financial aid. “I expect Casa (de Maryland) and places to come back and say, ‘These poor people now need financial aid. They need grants, they can’t even afford in-state tuition rates,’” Botwin said. Higher state taxes were only a matter of time, he said.

About 42 percent of Marylanders voted No on Question 4, following a lackluster campaign against the law. Botwin said they were outgunned by a much larger coalition of advocates, who raised at least $1.5 million and registered themselves as a political entity, allowing them to campaign in a way that Help Save Maryland could not.

“We did get more votes than Romney did in Maryland,” Botwin said.

Lyn Beary was one of the community leaders working to persuade opponents of the law. “I think the very interesting thing to me is how effective one-to-one conversations are,” said Beary, a retired research chemist. “We talked to people one on one wherever, in the grocery store, in the gym, in my neighborhood and at work, and we asked them to talk to more people.”

“I made sure that anyone who would listen to me would know what the law says and not vote in a way that they didn’t intend if they knew the law,” Beary said. “That’s how it went, one person by one person by one person.”

Many immigrants enter the country legally but fall out of status later, advocates pointed out. “There are lots of reasons why someone is undocumented that really have more to do with the way our immigration system is than any fault on their part,” Beary said.

Botwin isn’t giving up on his opposition to the law. He plans to contact colleges and universities to monitor the number of undocumented students who are paying in-state tuition rates, and return to Annapolis to challenge the state to recalculate the costs of the law based on what he expects will be enrolment numbers that exceed previous government estimates.

“I want to show how bogus this whole thing was and why it’s a mistake,” Botwin said. “At least let people know that they were hoodwinked by their public officials.”

Law supporters aren’t giving up either. They hope to hold up Maryland as an example to the rest of the country.

“We’re hoping this sends a message to Congress and to other states,” said Kristin Ford, spokeswoman for Educating Maryland Kids. “This victory in Maryland can set the tone for a broader conversation about people in our state, in our country, in our schools, who don’t have documentation and who care deeply about this country, and who want opportunities to further their education and contribute to their country. There is public support for them.”

Beary thinks such a step is good for the public at large.

“People who have the opportunity to develop their talents to the best they can are happier, more contributing members of the community and they earn more money and contribute to the tax base,” Beary said. “I would rather have an educated person, and not a frustrated person, in our community.”

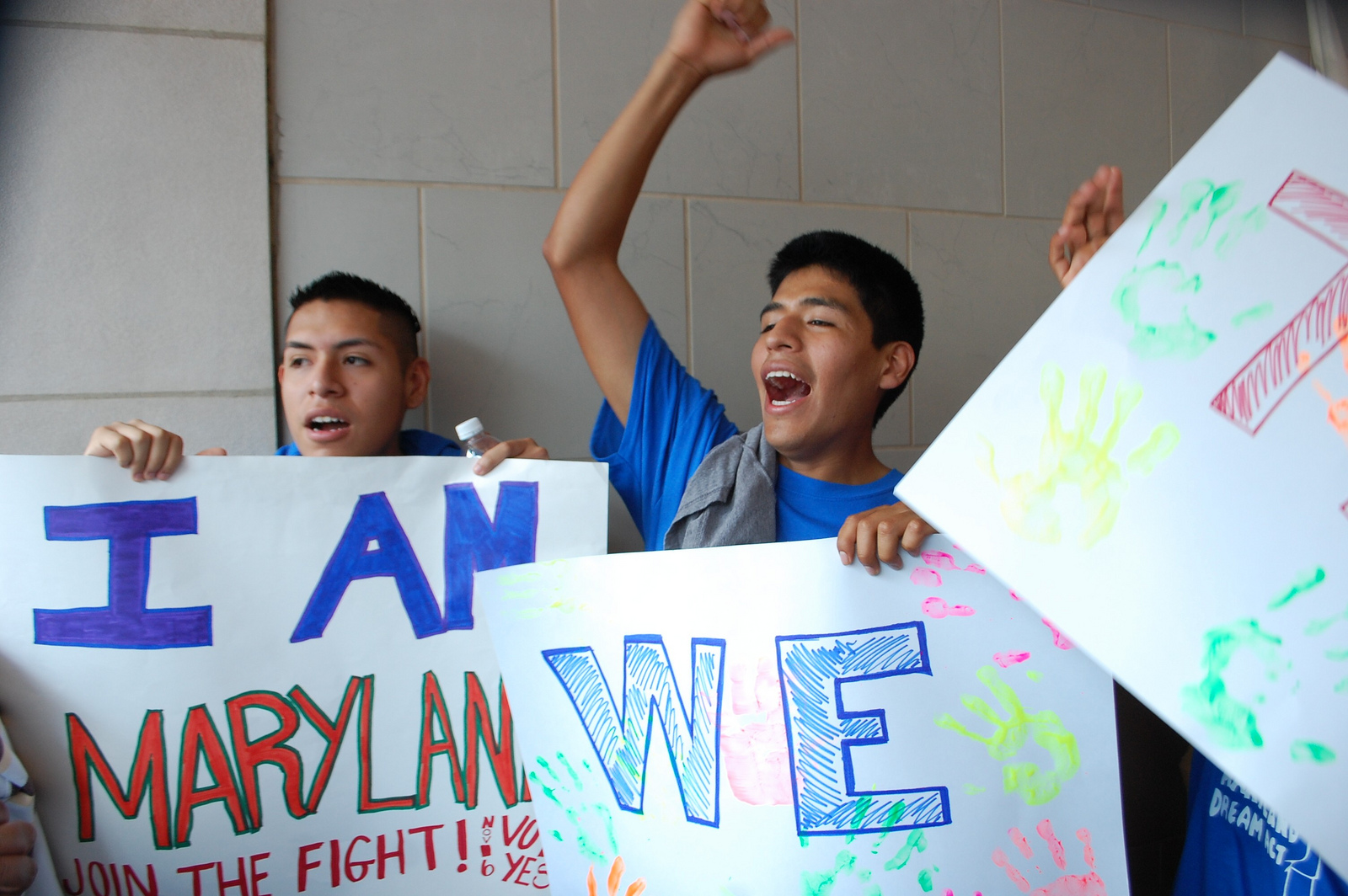

Photo from an August 2012 Maryland Dream Act Rally by mdfriendofhillary via Flickr.