There are now two different versions of African-American history. The first is the inspiring story of slaves who were given their freedom after the Civil War. The second is the tale of a harsher reality in which black Americans have moved from slavery through a series of lesser racial caste systems over the last 150 years. Many of America’s young black men are ensnared in the second story.

![]()

The lives of these young men are controlled by what author Michelle Alexander describes as “the new Jim Crow.” The old Jim Crow was a series of laws that limited the freedom of black people after emancipation. When the Jim Crow era ended with the civil rights victories of the 1960s, Alexander says, a new, more colorblind system emerged, based on law-and-order politics, that leads millions of young black men to drop out of school and end up in prison. Along the way, they are denied literacy skills, a family life, a job and full citizenship in the United States.

The lives of these young men are controlled by what author Michelle Alexander describes as “the new Jim Crow.” The old Jim Crow was a series of laws that limited the freedom of black people after emancipation. When the Jim Crow era ended with the civil rights victories of the 1960s, Alexander says, a new, more colorblind system emerged, based on law-and-order politics, that leads millions of young black men to drop out of school and end up in prison. Along the way, they are denied literacy skills, a family life, a job and full citizenship in the United States.

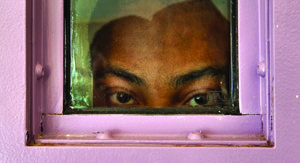

At the center of this story is a pervasive fear of “the other.” Dressed in baggy pants and carefully angled baseball caps, even the most mild-mannered young black men can sometimes trigger fear in the hearts of neighbors, teachers, employers and officials in the juvenile justice system, both black and white. Teachers are more likely to punish them for misbehaving. Police are more likely to stop them on the street. Judges are more likely to give them long jail sentences.

Unlike the old Jim Crow laws, the current caste system is not necessarily based on racial hatred, but it often serves the same purpose. Even liberal white Americans and middle-class blacks like Alexander – people who see themselves as defenders of racial justice – are disappointed to discover that they have been part of a system that is basically discriminatory.

“Racial caste systems do not require racial hostility or overt bigotry to thrive,” Alexander says. “They need only racial indifference.”

To be sure, there are many boys who have earned harsh punishment. But there also are those who have been swept up in a system built on wrong assumptions. Once arrested, even innocent youths are encouraged to plead guilty and negotiate for a lesser punishment. And once they have criminal records, the door to brighter opportunities may be closed forever.

Until recently, Alexander, a law professor at Ohio State University, shared the widely held view that poverty and bad choices were leading a higher proportion

of young black males down the wrong path.

“Quite belatedly,” she says, “I came to see that mass incarceration in the United States had, in fact, emerged as a stunningly comprehensive and well-disguised system of racialized social control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow.”

While Alexander’s work focuses primarily on the incarceration rate for black young men, like-thinkers in the fields of education and youth development are applying these ideas in schools and universities and in some workplaces.

The experience of Terrell Townsend, 18, of Washington, D.C., shows how this new approach is offering a second chance to young men who already have been caught in the snare of the new Jim Crow.

Townsend served time in a juvenile facility after being arrested in connection with his role in a street mugging. While there, he was introduced to a program that has since placed him in a local charter school, where he is thriving. He has not solved all of his problems with school discipline, but his teachers suddenly see him as college material.

This special issue of Youth Today examines the plight of juvenile African- Americans in the education, justice and employment arenas of life. It was underwritten in part by the generous support of the Open Society Institute.

This story was originally published in the June-July 2012 issue of Youth Today.