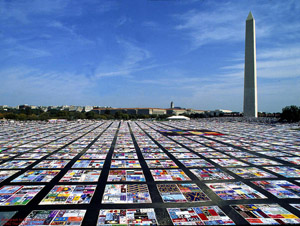

This summer, NAMES Project AIDS Quilt is blanketing Washington D.C. The Quilt consists of 48,000 handmade panels that memorialize sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, and friends who have died of AIDS. The Quilt is a beautiful, creative and overwhelming expression of grief and love. In honor of its 25th anniversary, the Quilt – the largest collaborative folk art project in the world – was unveiled as part of theSmithsonian Folklife Festival. And 35,000 panels are on display in dozens of locations around D.C. in conjunction with the International AIDS Conference being held here July 22-27. Hopefully, the presence of the Quilt around town will be a powerful reminder that AIDS is still a national health emergency, especially in the nation’s capital.

This summer, NAMES Project AIDS Quilt is blanketing Washington D.C. The Quilt consists of 48,000 handmade panels that memorialize sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, and friends who have died of AIDS. The Quilt is a beautiful, creative and overwhelming expression of grief and love. In honor of its 25th anniversary, the Quilt – the largest collaborative folk art project in the world – was unveiled as part of theSmithsonian Folklife Festival. And 35,000 panels are on display in dozens of locations around D.C. in conjunction with the International AIDS Conference being held here July 22-27. Hopefully, the presence of the Quilt around town will be a powerful reminder that AIDS is still a national health emergency, especially in the nation’s capital.

The first time I saw the Quilt was in the late 1980s, when its national tour made a stop in Philadelphia. Hundreds of volunteers participated in the carefully choreographed ritual unfolding of this giant cloth monument. Over the course of many hours, people solemnly recited long lists of the names of those who had died, usually adding the phrase, “and my best friend…” Visitors meandered through walkways, admiring the artistry of some panels and weeping at the devastating loss captured on others.

The Quilt experience was so moving that it jolted me into action. I felt I could no longer stand by while a preventable disease and government neglect were decimating my generation. I decided to take a break from my role as a journalist and do something that would have a more immediate and direct impact on people living with AIDS.

The Quilt experience was so moving that it jolted me into action. I felt I could no longer stand by while a preventable disease and government neglect were decimating my generation. I decided to take a break from my role as a journalist and do something that would have a more immediate and direct impact on people living with AIDS.

I became a volunteer with a local AIDS service agency. Compassion – and necessity – led the gay community to organize many volunteer-based programs to take care of their own: meal delivery to the homebound, legal assistance for victims of job and housing discrimination, even pet care. I went through training to be a buddy, a volunteer who provides emotional and practical support to a person living with AIDS.

I thought I would be assigned to a gay man; instead I became a buddy to a 5-year old boy born with HIV. To protect his identity, I’ll call him Rashid. His parents were recovering addicts; both had full-blown AIDS. Rashid lived with his mother and younger brother in the pleasant-sounding neighborhood of Strawberry Mansion, one of Philadelphia’s many neglected ghettoes.

On Saturday mornings, I’d pull up and park outside the worn-down row house on the busy street where Rashid lived. A white person in an entirely African American neighborhood, I looked out of place and, to be honest, felt that way too. I’d ring the doorbell and eventually someone would let me in. It took a few minutes for my eyes to adjust to the dark, since the lights were rarely on. The house smelled of cooking grease and Lysol. I’d climb the rickety stairs to the bedroom Rashid’s family shared, crammed with a queen size bed, twin bunk beds, several dressers and a TV that was typically blaring World Wrestling Federation matches. From her own bed, where she was usually resting or smoking cigarettes, Rashid’s mom

would give him his dose of AZT, the best AIDS treatment available at the time. Then she’d cover his face and head with baby oil and send him off with me for the day.

Rashid was first child in my life. I took him everywhere: to movies, children’s theater, the library, museums, the zoo, the beach, even to see the Harlem Globetrotters. We had lots of fun and we loved each other. Every once in a while, he didn’t feel so great. But most of the time, he felt fine and was just like any other kid, although he was small for his age and didn’t seem to be growing or thriving like his younger, HIV-negative brother.

Rashid was my Saturday pal for several years until a renewed passion for journalism led me to take a full-time job in Washington, D.C .When his mother died, I came back to Philly for her funeral. After that, Rashid and I exchanged a couple of letters, but eventually we lost touch. I soon started a family of my own; then, the busy life of a working parent made it hard for me to sustain long distance relationships. Still, I kept a photo of Rashid on my bulletin board and I thought of him often. I wondered if he was still alive and if so, what kind of life was he having.

About two years ago, I tried to track him down. I found him on Facebook, where it seems that all long-lost connections are rekindled. His page was filled with smiling faces, wedding pictures and photos of him hugging his kids. He looked the same: rail-thin, dark brown skin, sparkly eyes. Rashid was happy to hear from me. I was happy that he was an engaged father and family man.

About two years ago, I tried to track him down. I found him on Facebook, where it seems that all long-lost connections are rekindled. His page was filled with smiling faces, wedding pictures and photos of him hugging his kids. He looked the same: rail-thin, dark brown skin, sparkly eyes. Rashid was happy to hear from me. I was happy that he was an engaged father and family man.

But life isn’t exactly as it appears in a Facebook timeline. While writing this column, I revisited Rashid’s page and learned that his beautiful wife LaToya (not her real name) had recently died. A member of his wife’s family posted angry allegations to his wall, claiming he never informed her of his HIV status and that LaToya died of AIDS. This last revelation was especially painful and shocking to me.

Rashid is now the same age I was when he came into my life. He is alive, thanks largely to early diagnosis, medical care and other services provided by a caring AIDS community. How – in this day and age – could someone who has lived this disease from day one not tell the woman he loved about his diagnosis? Thirty years after the onset of the AIDS crisis, 25 years after the first stitch of the AIDS Quilt, is this disease still so stigmatized that people live and die in a shroud of secrets?

I tried desperately to track Rashid down to find the truth. It took a few weeks but we finally reconnected, first on Facebook, then by phone. He did tell LaToya about his HIV-status, but only when she tested positive after their daughter was born. It was a major betrayal. But, LaToya chose to stay with him and two years later they married. They were in love; they were a family. He took care of her through declining health and the opportunistic infection her body couldn’t fight off. Now she is dead and two young children are deprived of their mother.

None of this had to happen. Rashid knows that. At first, he didn’t tell LaToya because he was afraid of losing her. Now, he’s lost her forever.

He told me, “I am an example of the good and the bad of this disease. I am living proof you can live with AIDS and have children and be a great dad and have a loving family. But I’m also evidence of what happens if you don’t disclose to people.”

AIDS is the leading cause of death of black Americans ages 19 to 44. African Americans are barely 13 percent of the U.S. population but make up nearly half of those infected with HIV.

A new Frontline documentary called Endgame: AIDS in Black America investigates why HIV has become a disproportionately black epidemic in this country. Through in-depth research, powerful stories and interviews with experts, the program reveals how misguided public policy, religious-based homophobia and a longstanding culture where you don’t talk about your business in public enabled the spread of AIDS in the African American community. The program features frank reflections of NBA star Magic Johnson, AIDS activist Phill Wilson and civil rights movement icon Julian Bond.cause of death of black Americans ages 19 to 44. African Americans are barely 13 percent of the U.S. population but make up nearly half of those infected with HIV.

“The film is about race in America as much as it is about HIV — how a virus has exploited our inability to deal with our problems around race,” says filmmaker Renata Simone. “In part I hoped to show how the big, abstract social issues come to rest on people every day, in the limited life choices they face. The story of HIV in black America is about the private consequences of the politics of race.”

If you haven’t seen it yet, I highly recommend watching the whole two hours, which covers the AIDS epidemic in urban centers and the rural South. Frontline’s site includes a comprehensive timeline tracing the impact of AIDS on the black community.

When I see panels of the AIDS Quilt all over D.C. this month, I will be reminded of the more than 600,000 Americans who have died of AIDS, a tremendous loss to our country. I will think about Rashid, and consider the life trajectory of HIV-positive children who grow up without parents or in poverty. I will reflect upon those still living with AIDS, some who swallow a fistful of pills every day to stay alive. I will wonder how many Americans do not yet know they are infected. And, I will think about how the AIDS epidemic has shaped my own sense of the balance between government responsibility and personal responsibility.

Visiting the Quilt, I will revisit how, in the face of the AIDS crisis, for me, journalism was not enough. The late 1980s was a time of darkness, when friends of mine lost count of how many funerals they’d attended. I felt I had to leave the newsroom for a few years and instead of telling the story, I had to change the story. I needed to go to the frontlines of the war on AIDS, to the children and families living in the trenches. I’m convinced these intense, close-up experiences have made me a more compassionate person and a better journalist. Is there a cause for which you would pass up your press pass?

Aerial photo from National Institutes of Health.

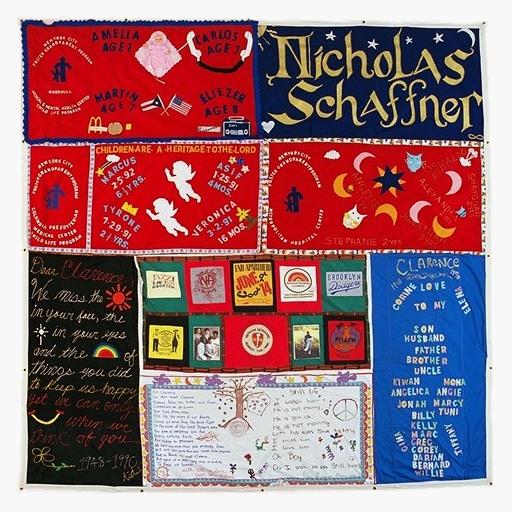

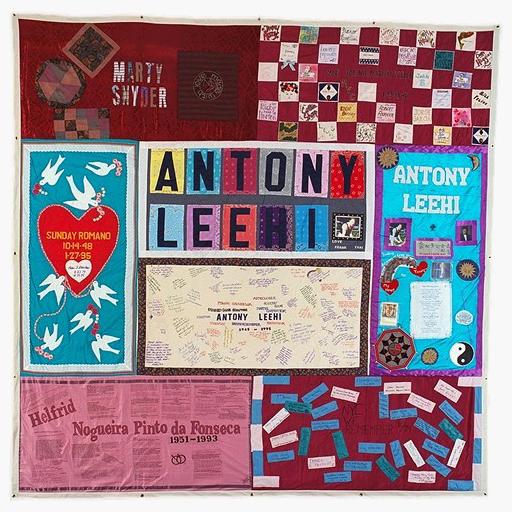

Quilt Panel photos from NAMES Foundation.