http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5635a2.htm

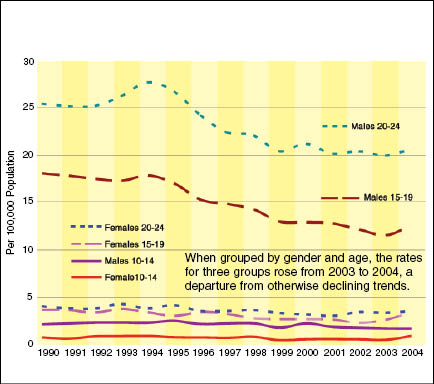

The CDC rang lots of alarms last month in reporting that suicides by youth and young adults (ages 10 to 24) rose 8 percent from 2003 to 2004.

“In surveillance speak, this is a dramatic and huge increase,” Dr. Ileana Arias, director of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, said in a teleconference coinciding with the release of the report. The report was published in the center’s Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

|

Suicide Trends |

| Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007 |

That “dramatic increase” translated to an actual rise from 4,232 suicides in 2003 to 4,599 in 2004 – an upturn of less than one person per 100,000 in that age category. Nevertheless, the increase is the largest in 15 years, and follows a decline of more than 28 percent in the number of suicides for that age group from 1990 to 2003.

But while the mass media made a big deal about the increase, the news might have sounded familiar to people in the youth field. And the reason that was widely given for the increase – less use of antidepressants – made no sense.

The reason for familiarity was that the same suicide figures were released in the CDC’s routine annual report on vital statistics last December. (See “Annual Summary of Vital Statistics,” Research of Note, March 2007.)

That report drew mild media coverage, much of which quoted a handful of experts who suggested that the increase in suicides was related to the introduction, in late 2004, of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s “black box” label on prescription antidepressants. Some studies have indicated that the labeling, which warned that the medications might increase risk of suicidal thoughts among youth, could have resulted in fewer prescriptions to youth suffering major depressive disorders. Such a decline, they speculated, might have led to an increase in youth suicides.

But the black box warning did not begin appearing on packaging until after October 2004 – too late to have much effect on the total number of suicides for that year.

Same Data, Different Spin

So why did the CDC repackage and release the data again in September?

“Somebody obviously must have gotten the task of finding a story for Suicide Prevention Week,” which was Sept. 9 to 15, said suicide expert John McIntosh, associate dean and professor of psychology at the University of Indiana, South Bend.

“These data have been there since December. If this was really that big a story, why wasn’t it out there in January?” he asked.

Maybe because the CDC hadn’t figured out the right news hook. The re-release of the data drew more publicity, in part because it highlighted a large percentage increase in the number of 10- to 19-year-old girls who committed suicide in 2004, though it was still a small number.

The headlines virtually screamed the news: “Girls’ Suicide Shock,” shouted The New York Post. “American Girls’ Suicide Rates Spike,” roared The Associated Press. CBS News weighed in with “Girls’ Suicide Rates Rise Dramatically; CDC Advises Prevention Programs to Focus on Gender and Age Groups Most at Risk.”

The stories focused on some findings that the CDC teased out from the data: that from 2003 to 2004, the suicide rate for girls ages 10 to 14 increased 75.9 percent, to 0.95 per 100,000 (for a total of 94 deaths), and the rate among 15- to 19-year-olds increased 32.3 percent, from 2.66 to 3.52 per 100,000 (from 256 to 355 deaths).

Once again, many of the stories focused on the speculation that suicides rose because antidepressant prescriptions declined.

Eventually, some stories pointed out that the number of prescriptions to youth ages 19 and under was essentially unchanged from 2003 to 2004. Although prescriptions did subsequently drop in 2005, the suicide numbers for youth and young adults that year are not yet available from the federal government.

How Significant?

While the raw numbers loom large because they reflect young girls taking their own lives, statistically speaking, “it’s not something that you’d make anything of,” said Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS).

“The fact is that you’ve got epidemiologists who know well that these numbers are first, small, and second, for one year. One year doesn’t mean squat.”

McIntosh, who has analyzed federal suicide statistics for years, reiterated sentiments that he and other experts expressed after last year’s release of the same data.

“It’s possible that there is really something here, but I don’t know how you could tell that,” he said.

However, suicide experts cite valid reasons to keep an eye on girls.

Girls are historically more likely to attempt suicide than boys, said Elizabeth Cauffman, associate professor of psychology and social behavior at the University of California, Irvine, and a member of the Girls’ Study Group at the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

According to AAS, the rate of attempted suicide is two to three times higher among girls than for boys, although boys are more likely to succeed at suicide. “The fact that [girls’] completion rates have increased is probably a function of methods,” Cauffman said.

Sure enough, the number of suicides by hanging/suffocation (which includes drowning and carbon monoxide poisoning) for girls ages 10 to 19 was “significantly in excess” of previous trends, according to the CDC’s September report. In fact, in 2004, hanging/suffocation was the most common method of suicide among girls ages 10 to 24.

“We’d like to think that part of that has been because we’ve been reasonably successful at … getting families to make firearms more inaccessible,” Berman said. “We know the firearm deaths have been coming down for several years.”

However, McIntosh notes that the decline in firearm deaths has been smaller than the increase in asphyxiation deaths, so that it’s not just a matter of one method replacing the other.

McIntosh, who said he was having a “real problem with all of the gloom and doom and exaggeration of a one-year trend,” said he rarely likes to talk about anything shorter than three- to five-year trends. “Some of the wording used brought greater alarm than you can do with a one-year data change,” he said.

“It’s not clear to me that you can draw absolute conclusions from this data, but that’s what a lot of people are trying to do. I would use the word ‘premature.’ But I can guarantee you that everyone is going to be looking at these numbers when the 2005 data come out in two or three months.”