|

|

A magnifier helps children look for living things in lessons on Earth science. |

Not long ago, Hands On Science Outreach was a perfectly fine after-school program, serving up to 40,000 youth annually, with facilitators trained in 42 states. But now HOSO is shutting down after nearly 27 years – which says something about how the after-school field has changed, for better or for worse.

HOSO represents the flip side of the nationwide boom in after-school programming: the vulnerability of simple, stand-alone operations in a field that is growing more competitive, focusing more on measurable outcomes and attracting larger operations with standardized curricula.

Maybe the demise of HOSO shows how standards in the field have evolved to be more demanding. But some observers also see a warning in stories like HOSO’s.

“What I’ve seen happen is this surrender to the free market, to a businesslike mentality” in after-school programming, says Diane Butera, who teaches community development at the Widener University Center for Social Work Education in Chester, Pa. When set against the “guideposts of a market economy, these little programs are extremely vulnerable. And they do provide important services.”

Inspiration

HOSO began because science educator Phyllis Katz couldn’t find a way to fulfill a more ambitious dream. During a lengthy family stay in Ontario, Katz was inspired by how the Ontario Science Centre’s creative, hands-on exhibits captivated the imaginations of her three children. After returning home to Maryland in 1980, Katz tried to create a local version of the center.

When that didn’t pan out, she started her after-school science program at a school in suburban Montgomery County, Md., outside Washington, D.C. The pre-K to sixth-grade curriculum emphasized hands-on learning – think making glue with milk and charting weather patterns – delivered once a week.

Sporadic grants over the years helped HOSO incorporate and expand, reaching its peak in the mid 1990s, says Beth Hess, HOSO spokeswoman. But HOSO remained primarily fee-based, with schools, nonprofits and parent groups paying about $310 for the eight-week curriculum, activity guides, materials and training. Each class served up to 11 youth.

In recent years, however, HOSO’s client base has shrunk. In 2004, José Luis Barata, a science education expert, was brought in as executive director to reverse what he describes as a 12-year decline. Katz retired from the program two years ago to become a consultant.

But HOSO found that it couldn’t change enough to meet the shifting demands of the after-school field.

Competition

For one thing, there wasn’t enough HOSO. While many kids attend one-hour programs once or twice a week – like soccer or martial arts – school-based after-school programs tend to run every day and for longer periods. “Today’s families have a hard time scheduling in little one-hour blocks,” says Jen Rinehart, vice president for policy and research at the Afterschool Alliance, a national advocacy organization.

There is also little room for programs that focus on one subje

|

|

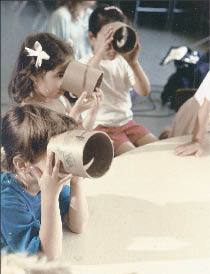

Fields of vision get narrowed with the help of tubes in a lesson on “My Environment.” |

ct and are not part of a larger offering. Holly Morehouse, state coordinator of the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program for the Vermont Department of Education, said programs like HOSO that are specific – “you do one thing and you do it well” – can work, but “need to fit into … this broader context” of comprehensive programming.

At HOSO, Barata says the model was so intricate that it didn’t mesh well with other organizations’ programs.

Also not helping was the federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Law, which has compelled more after-school programs to show that they can improve math and reading scores. The “evaluation culture” is particularly hard on small organizations, says Butera of Widener University. She says a lot of after-school programming has become standardized and packaged into “neat little boxes so that you can prove … your outcomes.”

HOSO aims to spark children’s interest in science, not to affect academic achievement. Thus it illustrates Rinehart’s point that “I don’t think that after-school programs are completely giving in to test taking.” But school officials looking for programs that show academic outcomes would not find that in HOSO.

They would, however, have plenty of other options. The implementation of NCLB is pressuring many programs to do more tutoring instead of enrichment, says Jason Freeman, director of the Coalition for Science After School. The coalition, made up of individuals and institutions from such fields as science, technology, math and youth development, seeks to boost science learning after school.

“When you hear that programs are being shut down because they’re not connecting to test scores, [it] is both disappointing and it’s a call to action,” Freeman says.

The bottom line is that with dozens of high-quality curricula available, “every curriculum is a competitor for every other curriculum,” says Robert Stonehill, chief program officer at Learning Point Associates, a nonprofit education service agency.

Too Late for HOSO

Barata arrived too late to save HOSO. “An eye needed to be kept on the trends and changes” over the past decades, he says, “and I’m not convinced that happened.” He says that was an “organizational problem. … I would not lay it just on [Katz’s] shoulders.”

This year, HOSO will serve about 20,000 youth in 35 states, the District of Columbia and three foreign countries. It’s earned income fell from $1 million in fiscal 2000 to $749,000 in fiscal 2005, according to its federal tax returns. Barata says government grants are running out, and sales have been declining while “the cost of building the kits was going up.”

The organization plans to shut down in the fall.

That means that Rozlyn Foster, education coordinator for Head Start of Greater Dallas, will have to come up with a new science component for her program. Foster says she is “sad to see it go,” agreeing that HOSO was costly, but also “convenient.”

Cheri Hayes, executive director of The Finance Project, which works to improve youth and family programs, would like to see more efforts to help small organizations adapt. “Sometimes researchers think about building quality as though the capacity of these small, community-based organizations was limitless,” she says. “We have got to think about how you create … aggregate capacity at the community level.”

Contact: HOSO (301) 929-2330, http://www.hosoprograms.org.