U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

Available at http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k7/newUserDepression/newUserDepression.cfm.

It’s one of the “chicken or egg” paradoxes of youth work: Which shows up first in teens, depression, or alcohol and drug use?

When you’re trying to prevent both, does it matter?

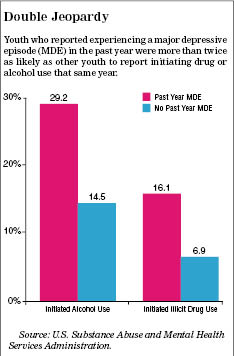

According to this report about the federal government’s 2006 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), youth ages 12 to 17 who reported a major depressive episode (MDE) in the 12 months preceding the survey were more than twice as likely as other youth to report having consumed alcohol for the first time in the past year (29.2 percent versus 14.5 percent).

Similarly, youth reporting depression in the past year were also more than twice as likely as non-depressed youth to report having used illicit drugs for the first time in the preceding 12 months (16.1 percent versus 6.9 percent).

People who work with adolescents will not be particularly surprised by the link between depression and substance abuse, admits Dr. Kenneth Thompson, associate director of medical affairs for SAMHSA’s Center for Mental Health Services.

What is important about the study, Thompson said, is that it suggests that kids who are depressed have a propensity to seek out alcohol and drugs at a young age and compound the problems of their depression.

“They are looking for some way to feel differently,” he said. “They may have a very jaundiced view of what the future is going to bring them, and therefore have none of the things that would stop them from doing behaviors that could get them into further trouble.”

|

In 2005, the year for which the survey questions applied, nearly 9 percent of all youth ages 12 to 17 (2.2 million) experienced at least one MDE. That’s defined in the survey as “a period of two weeks or longer during which there is either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure, and at least four other symptoms that reflect a change in functioning, such as problems with sleep, eating, energy, concentration and self-image.”

The percentage of youth experiencing an MDE increased with age, from 4.3 percent at age 12 to 11.9 percent at 17. Girls were three times as likely as boys to report having an MDE in the previous year (13.3 percent versus 4.5 percent). Rates of MDE varied little by racial/ethnic group: 9.1 percent for both whites and Hispanics, 7.6 percent for African-Americans, and approximately 6 percent for both American Indians/Alaskan Natives and Asians.

The most frequently reported drugs of initiation for both depressed and non-depressed youth was marijuana, followed by pain relievers, inhalants and hallucinogens.

The data showing the link between substance abuse and mental health issues supports the youth field’s movement away from the “silo” approach to creating and funding programs, toward more connected and comprehensive services that cut across disciplines. Adolescents “don’t come in as silos; they come in as whole individuals with a variety of problems,” Thompson said.

That poses an extra challenge, however, for the average youth worker.

“If [a youth] comes in, and they’re depressed … people need to start looking for the possibility of substance use as an issue,” Thompson said. “And if they aren’t using substances, to have a conversation with them about their increased risk for using substances and … strategies that may help them avoid falling into that particular trap.”