Photo courtesy of Moneythinks

Moneythink mentor Johnny Sullivan plays a financial literacy board game with students at Hirsch Metropolitan High School in Chicago where the students practice budgeting and saving to learn how to better deal with life’s unexpected financial hurdles.

By his own description Ted Gonder drifted through life as a teenager, aimless and “mediocre.”

However, with the help of several mentors he pulled himself together, drastically improved his grades and was accepted at the University of Chicago.

Once there, he saw impoverished neighborhoods surrounding the Hyde Park, Chicago, campus. He and a group of other college students decided to do reach out to teenagers in those neighborhoods. In 2009 their project spread to other campuses, and a year later it grew to become Moneythink, a nonprofit that engages college students as mentors to teach teenagers about money.

“Regardless of the amount of opportunity a student receives … knowing what to do with the funds you have is incredibly important,” said Gonder, now the chief executive officer of Moneythink.

“Many low-income first-generation college students who get scholarships have to drop out because unexpected expenses come up,” Gonder said. “They run into financial challenges.”

“Our goal is to help students stay on track,” he said.

Financial education is not a panacea for poverty, said Nan Morrison, president and CEO of the Council for Economic Education, a nonprofit that trains educators and advocates for financial literacy. But financial knowledge is enormously important for young people, she said.

They need these skills in order to make their dreams and possibilities come true, she said.

Overwhelmed by debt

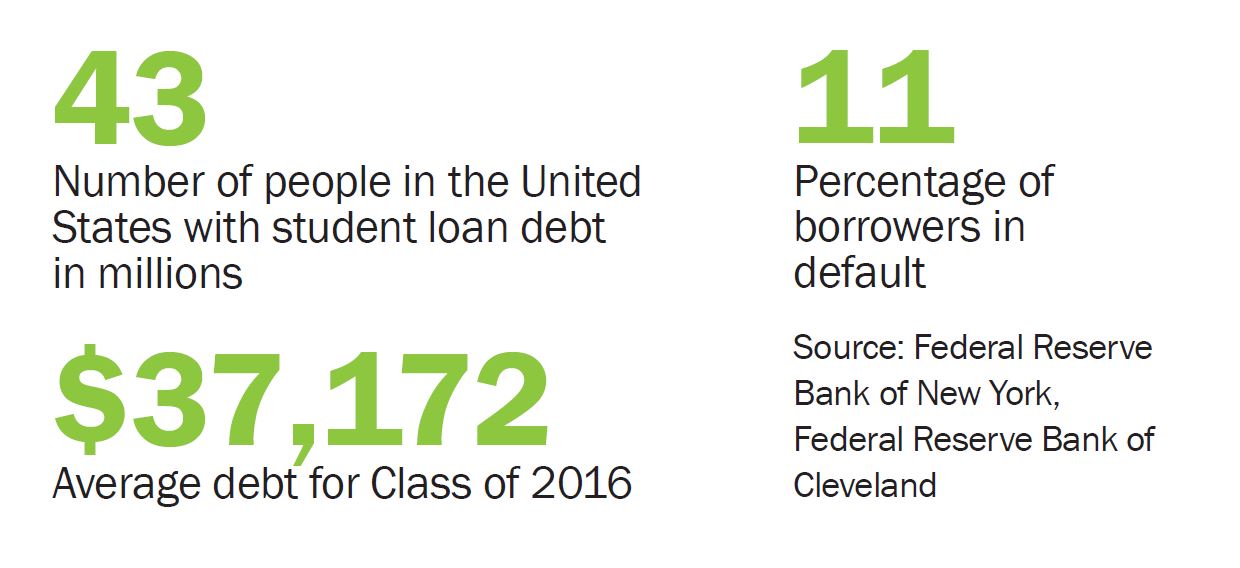

According to a 2014 survey by Wells Fargo, four in 10 millennials say they are overwhelmed by debt.

Sixty-seven percent have no “rainy day funds,” 60 percent aren’t saving for retirement, and 43 percent use costly non-bank borrowing methods, according to a 2014 FINRA Investor Education Foundation study.

Sixty-seven percent have no “rainy day funds,” 60 percent aren’t saving for retirement, and 43 percent use costly non-bank borrowing methods, according to a 2014 FINRA Investor Education Foundation study.

Financial education is especially needed among young people who are low income and don’t have a safety net, Morrison said. They have higher risks of running up student debt, she said.

Gonder points out that if an unexpected expense of $500 or $1,000 can derail someone, then their opportunities are restricted.

Gonder points out that if an unexpected expense of $500 or $1,000 can derail someone, then their opportunities are restricted.

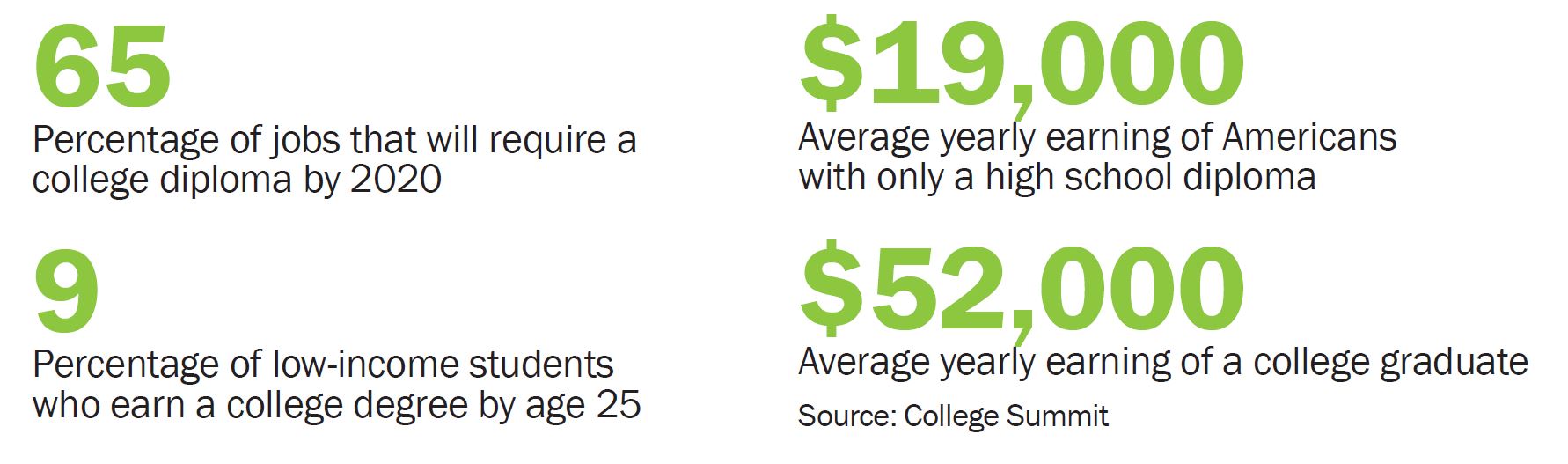

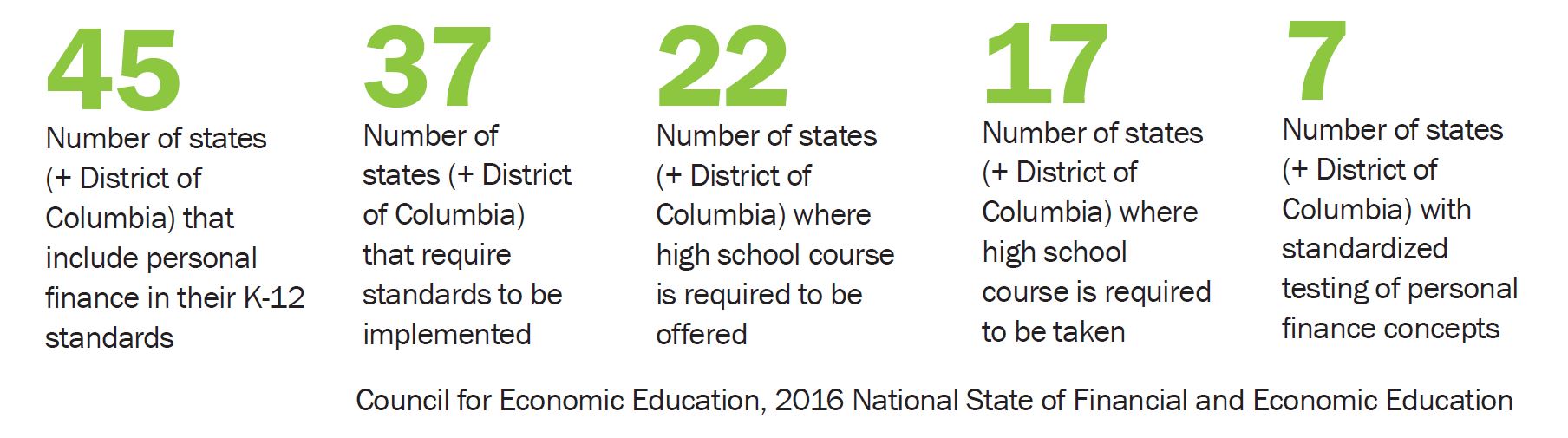

But despite the need, most schools aren’t teaching teenagers about money. Only 17 states mandate a personal finance course in high school, according to the Council for Economic Education. The number of states requiring kids to take an economics class dropped from 22 to 20 last year, according to the council.

Gaining money skills

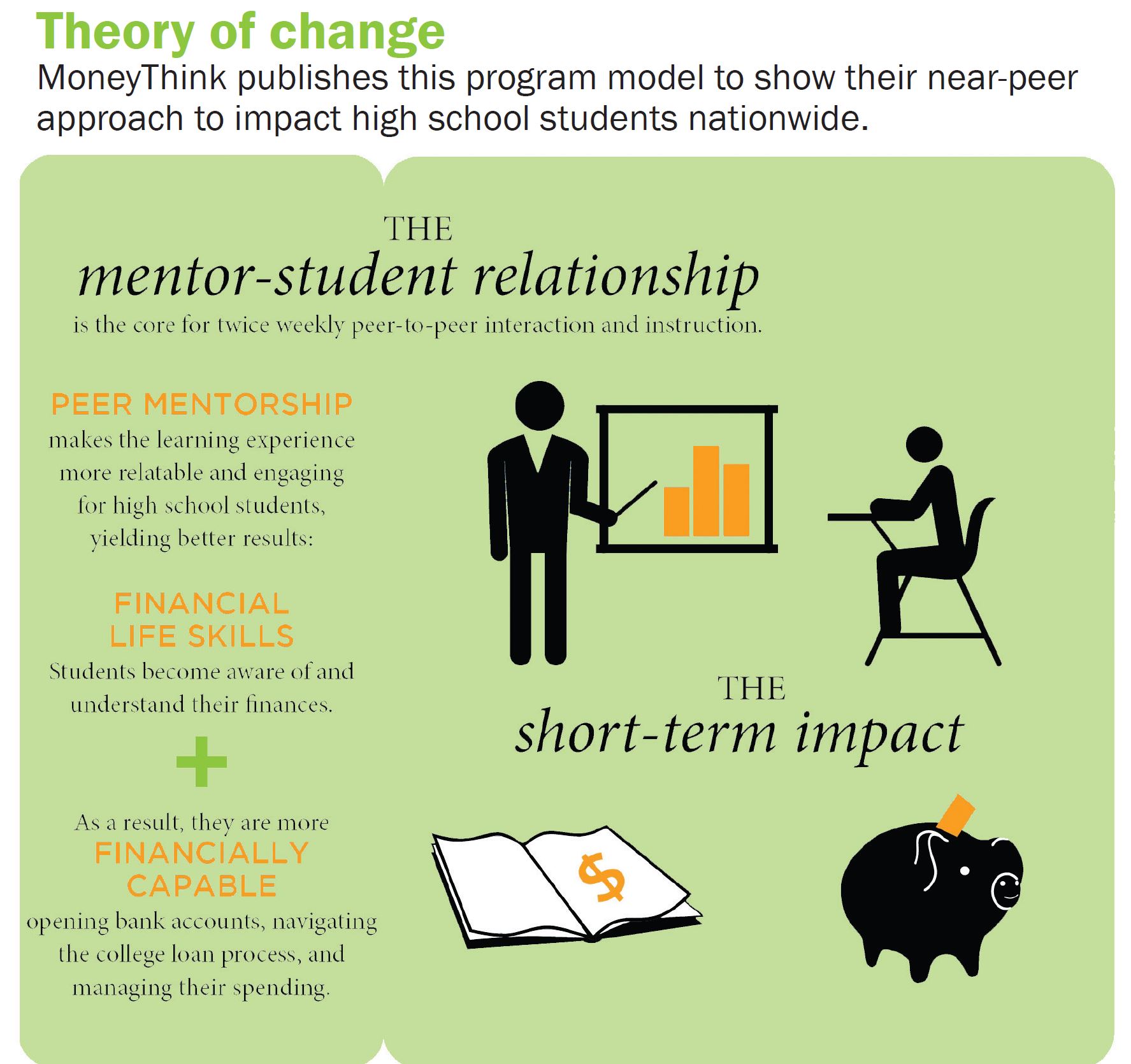

Last year, Moneythink chapters on 30 college campuses worked with 2,100 high school students. College-student mentors taught high school kids in a 21-week program during school hours.

”We are here to learn how to spend money mindfully, how to save money for the future, how to use money safely, and how to make money,” they tell the teens.

At each meeting they put kids into small groups and offered lessons spiced with a lot of pop-culture references.

They teach this rule-of-thumb:

- Pay yourself first.

- Spend less than you make.

- Follow the 20/30/50 rule. Put 20 percent into savings, spend 30 percent on wants and desires, and put 50 percent toward your needs.

Moneythink has developed a phone app to help kids apply the week’s classroom lesson to their lives. Kids use the app to take pictures illustrating the financial decisions they make. They comment on the photos with emojis.

“We realized that we needed to be doing more than just teaching knowledge. We needed to be helping students actually translate that knowledge into habits and behaviors outside of the classroom,” Gonder told Built in Chicago, a website for Chicago start-up businesses.

Moneythink focuses on young people who are getting ready for college or entering their first jobs. The young people learn how to choose a bank, use credit cards carefully and navigate the fees on prepaid bank cards.

The goal is to help them learn how to manage their first paychecks, deal with student loans and keep from being derailed by financial problems.

“If we can prevent a lot of these mistakes in the first place, then on the whole we can create a society that’s better off,” Gonder said.

This past summer [2016] Moneythink began working with After School Matters in Chicago to provide an additional program through that youth organization.

In youth development organizations

Some long-established youth organizations also teach financial literacy with the goal of interrupting poverty.

The Boys & Girls Clubs of America, for example, has a program called Money Matters for kids ages 13 to 18. More than 500,000 young people in more than 1,700 Boys & Girls Clubs across the U.S. have participated in it since 2004.

Among them is Wendy Kha, now a senior at Galileo Academy of Science and Technology in San Francisco. She attended a Boys & Girls Club in the Tenderloin area of San Francisco, a neighborhood known for a high rate of homelessness, drug addiction and crime. “The most helpful part [of the program] was about budgeting,” Kha said. She learned how much she needed to allow for food, clothing and other expenses — and how much to save.

“The majority of kids don’t know how to save,” she said. When they get a paycheck they want to buy something. But it’s important to always pay yourself by saving, she said.

She gives some to her parents each month to go toward food and utilities. “I come from a low-income family,” she said, and she is putting away money to use toward her expenses in college.

Kha became a counselor-in-training to help other kids manage money, and she was named the “Money Matters” national ambassador for the Boys & Girls Clubs.

Money Matters teaches:

— Budgeting and living within your means

— Saving and investing

— Planning for college

— Using credit and debt

— Becoming an entrepreneur

“The Money Matters curriculum provides [teenagers] with the knowledge they want but have nowhere else to get,” Damon Williams, senior vice president and chief educational and youth-development officer for Boys & Girls Clubs, told the Wall Street Journal.

Recommended practices

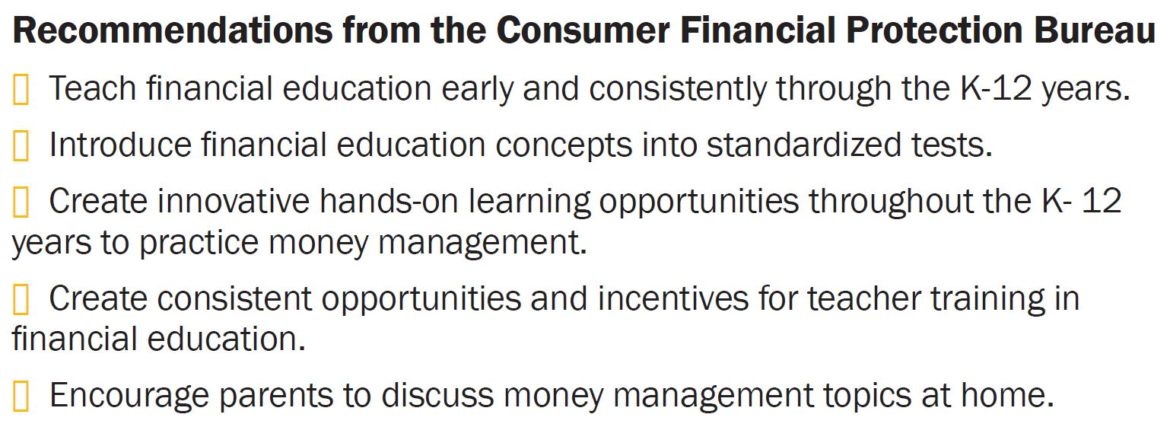

Eight years ago the New America Foundation and the Citi Foundation surveyed what was known about the effectiveness of financial education for youth. They concluded that financial education should be first introduced in the elementary school years. It should be made relevant to kids and should be connected with real-world financial activity, States should mandate it in their academic standards, they said, and both in-school and out-of-school education is needed.