Elaine Korry

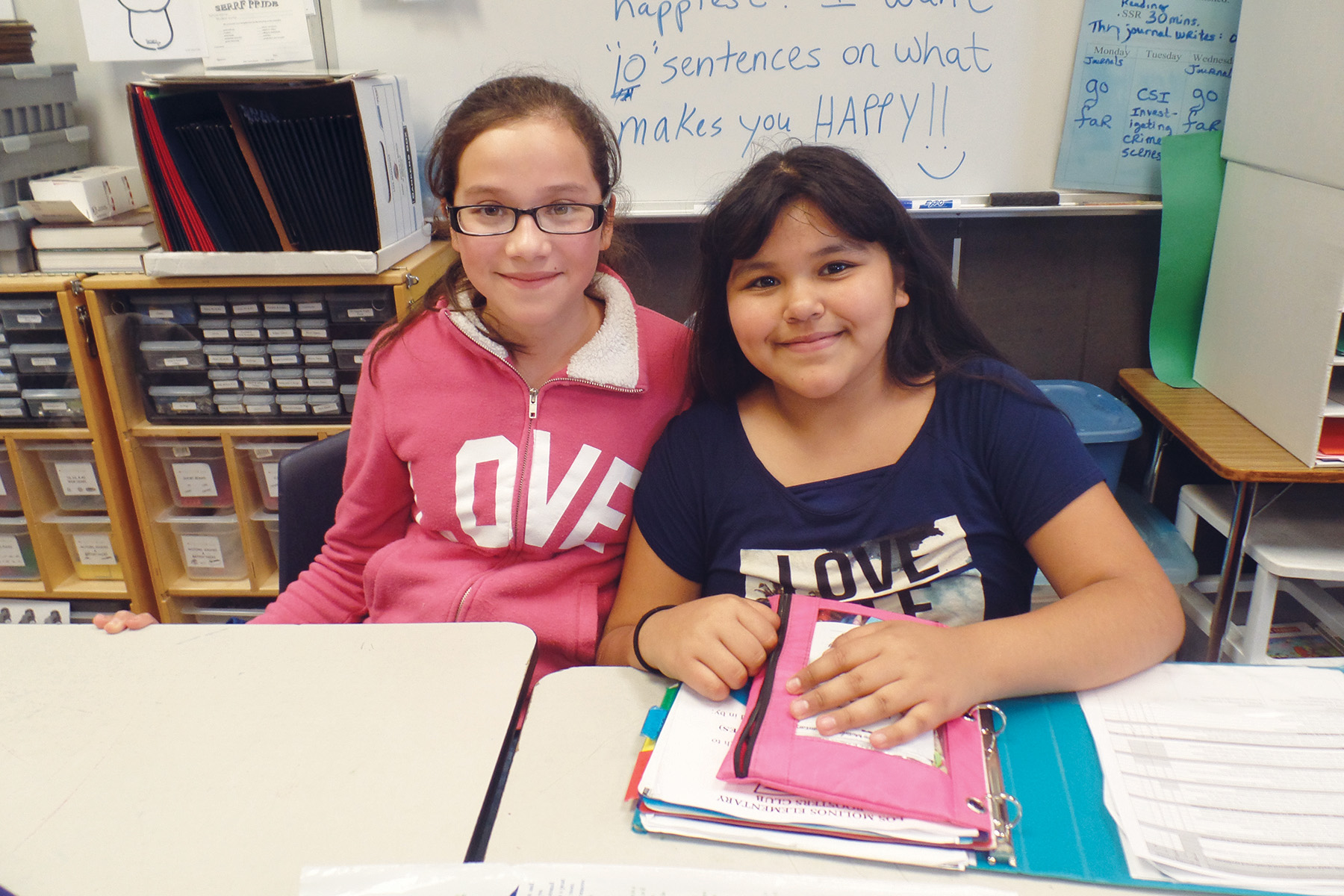

Fifth-grade students Giovanna Cota (left), and Briseyda Morfin (right), can get help with their homework during the first hour of the SERRF program (Safe Education and Recreation for Rural Families) at Los Molinos Elementary School.

One in every five children in the United States — nearly 10 million students — attends school in what the Census Bureau defines as a rural area. And although states vary considerably, one in three schools nationwide is considered rural, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

Life in the country may offer children the benefits of clean air, natural beauty and a strong connection to their community, but the attractions of rural or small town life are often offset by economic disadvantages. According to research by the National Network of Statewide Afterschool Networks:

Poverty rates are higher in rural communities: 19 percent, compared to 15 percent in nonrural areas.

Nearly one-third of rural grade-school students qualify for federally funded free or reduced price lunch, compared to one-quarter of urban children.

It’s no surprise that higher poverty rates among rural youth often translate into lower educational attainment. Nationwide, 23 percent of low-income rural youth don’t graduate from high school, according to the Rural School and Community Trust Policy Program. And only 27 percent of rural youth enroll in college, compared to 37 percent in cities and 31 percent in suburban areas, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Few partners, fewer resources

Quality out-of-school time (OST) programs could help rural school districts and their students to flourish, and rural parents overwhelmingly support their children having access to have a safe, organized place to go with opportunities for learning when school lets out, according to “America After 3 PM,” a 2010 report by the Afterschool Alliance, a nonprofit group based in Washington, D.C., that advocates for access to quality after-school programs. (See op-ed “OST Programs in Rural Maine Make a Difference”)

But the same challenges that result in lower attainment levels also force remote districts to limit their youth-development and OST activities. According to the Afterschool Alliance, only about one in 10 children (11 percent) from rural areas participates in an after-school program, a lower percentage than in urban (18 percent) or suburban (13 percent) regions.

It’s not that remote communities don’t recognize the value of expanded learning, or desire to broaden their programs. But they’re up against some daunting constraints:

Rural areas have a limited local tax base, and therefore fewer funds allocated to education. The Harvard Family Research Project found that as a whole, rural schools have lower per-student after-school program funding through 21st Century Community Learning Centers than nonrural schools.

- In some parts of the country, a growing percentage of rural youth are immigrants — 1 in 4 in California — which results in unique cultural and language challenges, according to program administrators.

- Small towns don’t have ready access to the museums and theaters and science centers that urban districts lean on for enrichment opportunities. Without a local YMCA or Boys and Girls Club, the Alliance survey found that an after-school program is often a rural community’s only outlet for youth development.

- Part of the strength of a nonprofit organization’s application for funds is based on the partnerships they’ve built. Rural programs have fewer businesses, community groups or foundations they can turn to for support. “In some of these towns, there is a school, a couple of bars, maybe a church and a small grocery store,” said Michael Funk, director of the after-school division at the California Department of Education. “What kind of partnerships can you build there that match the opportunities of a more populated area?” he asked.

- Being remote also means rural districts have trouble finding and retaining qualified personnel. “Many of these programs are far from a university or community college, which tend to be a good source for youth workers,” said Funk. “In many cases the labor pool is very small anyway, so it’s very difficult for some programs to find staff.”

- Remote school districts also face high transportation costs and limited providers.

To overcome these challenges, service providers have to maximize existing resources, and build partnerships to ensure the viability of their services.

Wearing many hats

To keep their programs sustainable, administrators such as Susan Maschmeier must stretch their program dollars to the limit, sometimes serving twice the number of students budgeted for in their grants. “I have to constantly be looking under every rock for funding, and advocating for my program to anyone who’ll listen,” said Maschmeier, director of after-school programs for the South Bay Union School District in Eureka, Calif.

“Being rural means we have to wear many hats,” said Maschmeier. “If the superintendent needs to be a bus driver one day, then that’s what happens in some schools to make it work.”

Given the tough challenges to sustaining OST programs, parents of rural children surveyed in 2009 by the Afterschool Alliance reported that after-school options are either limited (57 percent) or simply unavailable (40 percent). An estimated 2.7 million rural children in the U.S. are left on their own when the school day ends.

Funk said that spells trouble for many unsupervised youth. “I’ve been to parts of California where the main industry happens to be methamphetamine,” said Funk. He said without a positive place to go when school lets out, “too many kids go home to a negative environment, and many of them wind up getting involved with drugs.”

“After-school programs have a proven track record,” said Maschmeier. “The challenge for rural districts is to be strategic and creative enough to overcome the obstacles that get in our way.”

For more information:

- “Why Rural Matters 2011-2012, The Condition of Rural Education in the 50 States” is a report of the Rural School and Community Trust Policy Program, which provides information and analyses to “highlight the priority policy needs of rural public schools and the communities they serve.”

- The Harvard Family Research Project has published a research update titled “Out-of-School Time Programs in Rural Areas,” which provides highlights from the Project’s OST Time Database.

- “America After 3PM: From Big Cities to Small Towns” is a special report from the Afterschool Alliance’s in-depth study of how America’s kids spend the after-school hours.

- Eighty-five percent of rural students in California live in poverty, and more than one in four are English Language Learners. In 2010 The California Afterschool Network hosted a summit on rural after-school, which resulted in recommendations to support those programs. View the report.

- The National Research Center on Rural Education Support at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill conducts focused research on significant problems in rural education.

Back to main article “Rural Youth Face More Economic Hardship, Have Fewer Enrichment Opportunities”