CHICAGO — Jesús Barrios was half joking when he offered to marry his lesbian friend. She was lamenting her mother’s constant pestering about marriage. He saw a direct path to legalization.

CHICAGO — Jesús Barrios was half joking when he offered to marry his lesbian friend. She was lamenting her mother’s constant pestering about marriage. He saw a direct path to legalization.

“The more you don’t identify with the norm, the more difficult it is to live your life,” said Barrios, a gay, undocumented 22-year-old student originally from Tijuana, Mexico. “We’ve come to a point where we’re comfortable being really vocal … We want people to know our community exists.”

Barrios is one of a swelling number of “undocuqueer” activists fighting for inclusivity in the twin pushes for immigration reform and LGBTQ rights. Although the term, undocuqueer, applies to a diverse group, a majority of leaders in this community are Hispanic.

There have been major wins for the LGBT community and, with the demonstrated weight of the Latino vote in the Nov. 6 presidential election, the undocuqueer movement is gaining more visibility and leverage in American politics, according to those involved in the movement.

“They’ve seen that their voices matter, that the Latino vote matters and is only going to matter more, especially as a very young demographic in the country and easily the fastest growing,” said Timothy Farrell, coordinator of the UndocuQueer Book Project, a compilation of narratives by undocuqueers from diverse backgrounds. “They know they can have an impact and that can only happen through speaking out.”

To create visibility and provide a safe space for other young people to come out and share experiences, Barrios co-founded a support group in his south-central L.A. community. Such collectives have sprouted across the nation in the past three years, led by young activists discontent with keeping a low profile. With vocal and organizational strength, they are connecting the LGBT and immigrant communities in the struggle to spur change.

“The fact that everyone is on social media now, it’s been a huge part of this and how it becomes visible,” Barrios said. “We’ve found an outlet to know how to organize ourselves … breaking away from [established immigrant rights organizations] and being autonomous.”

But establishing a unique undocuqueer identity without the larger movement for gay and immigrant rights hasn’t been easy. Barrios was subject to bullying and name-calling throughout his school days, in a neighborhood he describes as a place “not OK to be gay.” Now 22, he came out to most of his family three years ago but still hasn’t told his father. Living under the dual threats of deportation of his family and living paycheck to paycheck, Barrios found the best way to deal with his complex identity was to accept the particular reality of his daily challenges.

“There’s a mentality that’s instilled in us as people that come from countries where nothing is ever handed to you, and I think that’s helped me a lot,” Barrios said. “But I think about, when am I just going to get a break?”

For Southern California student activist Javier Hernandez, 23, his LGBT identity was an alienating factor within his undocumented immigrant community. His upbringing in a religious evangelical Mexican family and conservative town made it difficult for him to find a space where he could be himself. Speaking out and getting involved within the youth activist space helped Hernandez connect with others nationwide who shared his experiences.

Hernandez said political involvement like grassroots organizing protects him against authorities and the danger of deportation – and so does community support. While people in his situation do not necessarily need to choose between two identities, he said, living with this complex identity can be very isolating. Societal – and legal – pressures can make it seem like opportunities, educational, professional and even spatial, are very limited, and a supportive network is essential.

“In the undocuqueer community there’s a lot of mental health issues that aren’t addressed: depression, attempted suicide,” Hernandez said. “ We need to get to a place where we’re able to speak more about our mental health.”

Like Barrios, Hernandez is striving to provide such a space for other undocuqueers. Both have taken part in Farrell’s UndocuQueer Book Project. Many activists featured in the book are leading figures in the movement who seem to “have it all together,” especially in the way they’re able to publicly and proudly speak out about their situation and grievances. But Farrell said he was surprised by how many of them had, at a point, contemplated or attempted suicide.

“It helps LGBT people,” Farrell said, “to hear that there’s something unique that they should consider, [it helps] undocumented people to hear that there’s a safe space for expressing your full identity, and then [it helps] people who are afraid to hear that there are other people out there and support systems – and that things do get better.”

In addition to empowering others to embrace their full undocuqueer identity, Barrios and Hernandez agree that the larger movement’s goal is to gain more inclusiveness in the immigrant and LGBT activist spaces.

“Some of the policies or legislation that are being pushed by both [mainstream LGBT and immigrant rights organizations], sometimes we as undocuqueer people don’t benefit from them,” Barrios said.

The main piece of legislation impacting undocuqueers specifically is the Defense of Marriage Act. Implemented in 1996, this act defines marriage as a legal contract strictly between one man and one woman.

As a result of DOMA, “none of the estimated 40,000 bi-national and dual non-citizen same-sex couples in the United States are eligible to use the immigration mechanisms available to different-sex spouses,” according to the Williams Institute, a think tank based at UCLA Law school focused on researching sexual and gender identity in public policy. Same-sex couples are categorically denied the right to family reunification that heterosexual couples are granted.

The Obama administration has announced it will not defend DOMA in federal court. Congressional support for the Uniting American Families Act, which would give family reunification rights to gay couples, is at an all-time high with 139 co-sponsors across party lines. With increased visibility, undocuqueers spearheading the immigration movement may have cracked open a window of opportunity as President Obama starts his second term.

“We felt a huge win in this election,” Barrios said. Despite the fact that deportations hit a record high during Obama’s first term and LGBT inclusion is still in its infant stage, the undocuqueer movement gained a grassroots victory. “Folks out there were campaigning for both the DREAM act and marriage equality; it’s really powerful to see what we’ve been working toward in practice.”

Moving forward, Barrios said he hopes the undocuqueer movement builds partnerships with other minority, marginalized communities, and holds allies accountable to their claims as resources. Intentionally addressing the undocuqueer reality, not just in grassroots organizing but also in the national conversation, is part of the solution to providing needed opportunities to thrive.

On a personal level, Barrios graduated college in December and has applied for the Deferred Action Childhood Arrival program – which could allow him to get a work permit and temporary protection against deportation. He is also looking to move to the East Coast to reunite with his partner.

“For so long, being undocumented, you fight for goals that you’re going to put on pause,” he said. “But now at least at one point in my life I’ll be able to do something for myself and enjoy the next step.”

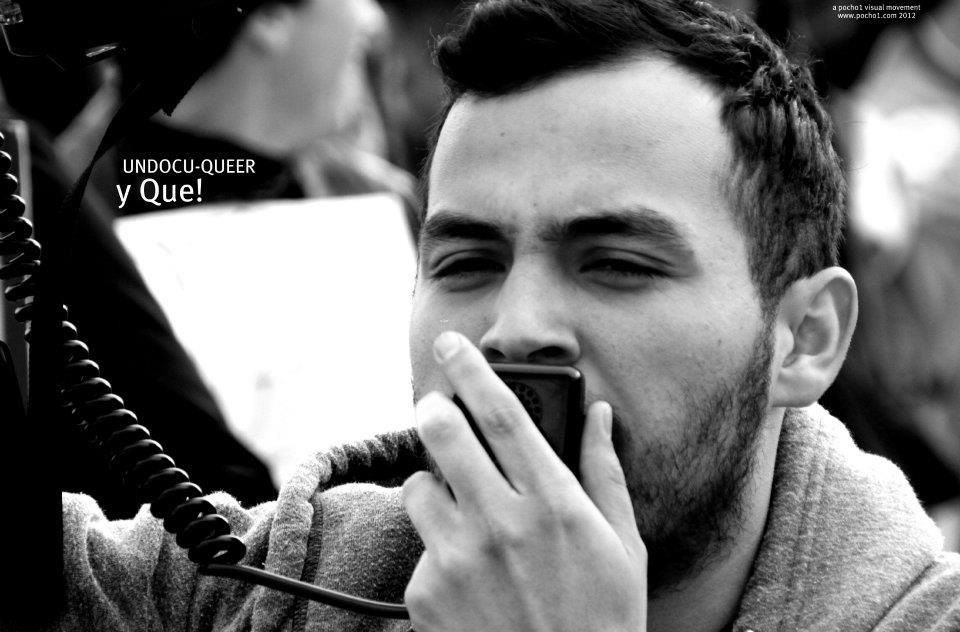

In photo above is Jesús Barrios, a gay and undocumented activist from Mexico who is pushing for more rights and inclusion of the undocuqueer population.

Photo courtesy of Jesús Barrios.

Leah Varjacques is a writer for The Chicago Bureau.