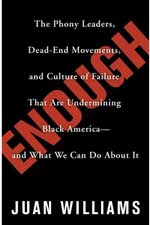

By Juan Williams

Random House

256 pages; $25

You might not be able to judge a book by its cover, but you can sometimes judge a book by its title – and few book titles are as direct and provocative as this one by National Public Radio correspondent Juan Williams. It presages an “in your face,” “tell it like it is” narrative that is sure to please some and upset others.

Williams, an African-American, has had “enough” of contemporary black leaders, politicians, civil rights organizations and black churches, all of whom he sees as failing the black poor by being silent about critical ways the poor could help solve their own problems. Williams even equates some of today’s black leaders with “Judas, the biblical traitor.”

What is it about today’s black leadership that provokes such an outburst? To answer that, we must go back to 2004 and America’s most beloved father figure, William H. Cosby III.

On May 17, at a gala in Washington celebrating the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, Cosby set off a firestorm with a speech criticizing the negative norms, attitudes and behaviors of poor blacks that keep them impoverished and marginalized at a time when many others, including the black middle class, are making significant social and economic gains. Cosby rejected the notion that white people were responsible for the condition of the black poor, saying that “lower economic and lower middle economic [black] people [are] not holding up their end in this deal.”

In his criticism of poor blacks, Cosby censured parents who fail to parent their children and who buy $500 sneakers but “won’t spend $250 on Hooked on Phonics.” He also criticized young blacks for having “their pants down around their crack” and “her dress all the way up to the crack – and got all kinds of needles and things going through her body.” Black children, according to Cosby, are “standing on the corner” and “can’t or don’t want to speak English.”

Criticism of the critic was swift. Ted Shaw of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund wrote in The Washington Post that Cosby “demonized poor black people.” Dr. Michael Eric Dyson of the University of Pennsylvania declared that Cosby’s speech “betrayed classicist, elitist viewpoints that are rooted in generational warfare.”

This is the maelstrom into which Williams has inserted himself, firmly on the side of Cosby. Williams (a Youth Today board member) supports Cosby with compelling historical and statistical evidence. He also criticizes contemporary black leaders, including church leaders, for failing to condemn black-on-black crime, lead demonstrations against drug dealers or speak out against the epidemic of black children being born to single young women. Williams is especially pointed in his criticism of such leaders as Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton and the NAACP.

“It is time to throw off the culture of poverty,” Williams writes, “and take inspiration from a history of black sacrifice aimed at opening doors for future generations of black people.” He says there are “proven steps” out of poverty, specifically, “getting a good education, getting married and being good parents,” and he provides statistical evidence to prove it. Quoting Shelby Steele, Williams writes, “You cannot get out of poverty unless you take an enormous amount of personal responsibility for doing so.”

Few would argue against these principles. The problem lies not with the principles themselves, but in how to fulfill them. If personal change were merely a matter of will, thousands of psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers would be unemployed tomorrow.

The desire to change needs to be nurtured and supported by others. The single mother who wishes to complete her education and boost herself out of poverty also needs affordable day care, which might not be available. Youths who want to go to school and learn often face dilapidated buildings, ill-equipped classrooms and teachers who are less than the cream of the crop.

Nevertheless, Williams has written a compelling book that will force readers to face their basic assumptions about black life and black communities. With eloquence and passion, he conveys a sincere desire to see improvement in the lives of poor blacks, and a strong frustration with so-called black leaders he sees as standing in the way.

You may disagree, as I did, with one statement or another. But I found it hard to quarrel with Williams’ basic thesis that the key to improving the lives of poor blacks is in their own hands. At the same time, they need the kind of help that we, the black middle and upper classes, must provide.