Levi Sharpe

A woman sleeps on a bench in front of St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. The church provides services to LGBT homeless youth.

NEW YORK — Ivan Cabrera came home crying.

“He died. My boyfriend died,” Ivan wept. “Harry is my boyfriend, Mom. I’m gay.”

Cabrera had just watched Harry jump to his death in front of a train after they both came out as gay at their school. His mother looked at him, stunned, and then cursed at him. She cried and yelled, and told her son not to touch her because he would spread a virus.

Lena Masri

Ivan Cabrera

He was 12 years old.

That is how Cabrera describes one of the many fights he had with his parents at their home in East Harlem, New York.

“I always felt when I was younger that I was never loved, never cared about,” said Cabrera, now 22.

Cabrera said his mother kicked him out of the house when he was a teenager because he was gay.

His mother and two sisters give different versions of the story but agree that Cabrera would often run away from home and disappear — missing for days or weeks.

Runaway or ‘throwaway’ youth

Almost 20,000 children were reported missing in New York state last year, and nearly all of them — 96 percent — are suspected runaways like Cabrera, according to the 2014 Missing Persons Clearinghouse Annual Report. Runaways are defined by the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services as children under 18 who are missing from their homes without their parents’ consent.

Most leave home because of conflicts with their parents, authorities say.

“Each year the No. 1 reason young people reach out to us is family dynamics,” said Maureen Blaha, executive director of the National Runaway Safeline, an organization that works to keep runaways and homeless children safe.

“It could be some sort of conflict in the home. It might be because the parents are fighting or because of issues with siblings.”

Last year Safeline received more than 96,000 calls from runaways. Nearly a third were from New York — more than any other state.

Some of the children left home after they came out as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, said Blaha.

LGBT young people make up about 40 percent of the 500,000 young homeless people in the country, despite comprising only about 5 percent of the overall youth population, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless.

“Family rejection due to homophobia, very often in conservative, religious families, is what accounts for that disproportionality,” said Carl Siciliano, executive director of the Ali Forney Center, a New York City-based nonprofit organization that advocates for the safety of homeless LGBT young people and collaborates with the National Coalition for the Homeless. “Sometimes the kids are thrown out, other times the parents’ rejection is so hard to deal with that the kids choose to leave.”

“Family rejection due to homophobia, very often in conservative, religious families, is what accounts for that disproportionality,” said Carl Siciliano, executive director of the Ali Forney Center, a New York City-based nonprofit organization that advocates for the safety of homeless LGBT young people and collaborates with the National Coalition for the Homeless. “Sometimes the kids are thrown out, other times the parents’ rejection is so hard to deal with that the kids choose to leave.”

Cabrera’s mother, Nydia, said she didn’t throw her son out of the house and never had a problem with her son’s being gay. “He is my son regardless,” she said.

She said she doesn’t remember anything about his coming home crying because Harry had died. But she does remember that he started running away when he was around 15. He would leave, come back home and then disappear again.

“I would go look for him,“ she said. “I was upset and angry. I don’t know where he was. He never wanted to talk about it.”

The problem with shelters

The main problem is that there are only 4,000 beds for 500,000 young homeless people, Siciliano said. “Hundreds of thousands of kids not having access to shelters is a national disgrace,” he said. Another problem, according to Siciliano, is that shelters are very large. “The larger the shelter, the more likely it is that LGBT young people will experience bullying and hate crimes.”

Levi Sharpe

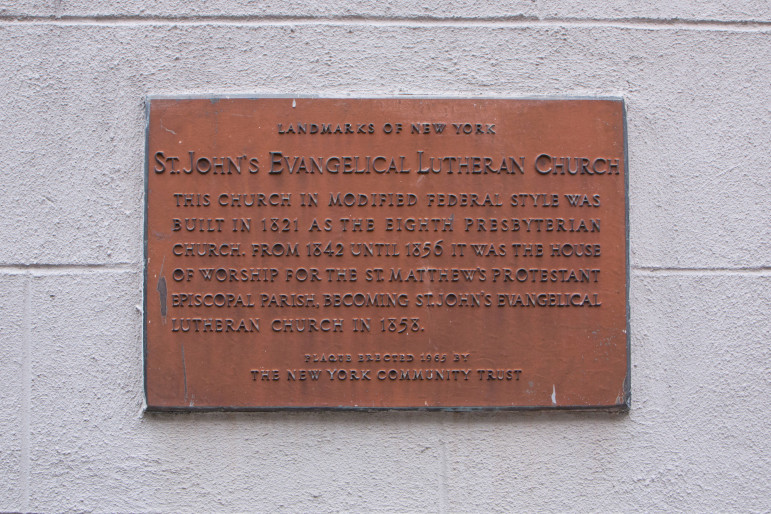

St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. The church provides services for LGBT homeless youth.

A third issue, said Siciliano, is that many LGBT-specific programs are religious or related to churches. “It’s really important that homeless LGBT kids aren’t put through religious pressure. Many projects for homeless LGBT kids are run by religious institutions and young LGBT people are likely to have been made homeless because of religion. So Bible study can be retraumatizing for the kids. They were told by their parents that they were unacceptable to God. Then when they have to read the Bible [at] the only place they can go it makes it harder, and may make them not want to go there.”

Supports for runaway youth

Since he was 16, Cabrera has been spending time at New Alternatives, a drop-in center for 16- to 24-year-olds who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender — and homeless. He goes there almost every Sunday for a free meal, HIV testing and a talk with other clients and caseworkers.

New Alternatives defines “homelessness broadly to include youth living on the street; youth in shelters, transitional living programs, and foster care; youth who are ‘couch-surfing;’ and youth who are trading sex for a place to stay.”

Cabrera calls the people there his family.

“He used to say that his mother was very homophobic,” said Kate Barnhart, New Alternatives’ executive director. “He would sometimes go back to his mother’s place, but he would come back with horror stories.”

Cabrera’s sisters describe the home as turbulent.

“Ivan would leave for days and nobody knew where he was,” said Cabrera’s older sister Alicia. “When he came back, my mom would say, ‘Where were you?’ and ‘Don’t do it again.’ As she said that, Ivan would be packing a bag to leave again.”

As with many people who run away, it is not easy to give a reliable picture of what exactly Cabrera has been through or why and when he left home.

“I think a lot of families have issues with shame, and they hide things from outsiders,” said Barnhart. “I think in any family, they are going to have as many stories as family members. But kids who leave their home usually have a good reason.”

Notes from Cabrera’s files with New Alternatives tell fragments of his story:

On July 27, 2010, when Cabrera was 17: “Housing: Kicked out by mother staying w friend.” “Food – client has no food; needs pantry.”

Feb. 15, 2011: “Concerned about little sister’s upcoming birthday.”

Feb. 22, 2011: “Housing: Mom kicked out; sleeping on train. Basic needs: Gave blanket, underwear, hygiene supply.”

March 29, 2011: “Mental health: Crying about maternal rejection; talked about self harm.”

May 17, 2011: “Basic needs: Asked for referrals to food pantries/soup kitchens in Union Sq area – gave list.”

According to the files, Cabrera was referred to Sylvia’s Place, a shelter for homeless LGBT people, on April 1, 2011.

Ladedra Brown, overnight client services assistant at Sylvia’s Place, remembers Cabrera’s first night at the shelter. He came in covered in dirt, she said.

“I think he had been sleeping on the street,” she said. “And he slept hard that night — like he hadn’t slept in a long time.”

Levi Sharpe

A police officer patrols Christopher Street in Greenwich Village.

Cabrera said he was, indeed, sleeping on the street. Sometimes he spent the night in parks, other times on sidewalks and even inside big cardboard boxes, he said.

He says he often stole to make quick money and would sometimes trade sex for cash.

“It made me feel dirty,” he said. “I felt like it was disgusting. I didn’t want to put myself in that type of risk or danger, but I had to survive.”

Siciliano, of the Ali Forney Center, estimates that more than 50 percent of homeless LGBT young people have experience with survival sex.

“It’s very common,” said Siciliano. “Sometimes they trade sex for money, other times they trade sex for shelter.”

Cabrera said he tried to get internships and jobs, but no one wanted to hire him because he smelled and didn’t look presentable.

At 18, he often slept in Union Square. One day his mother found him there. “I thought she was going to hit me,” Cabrera recalled. “But she was actually pretty happy, and she said, ‘You are going to stay with me, and I’m so sorry.’”

Cabrera said he moved back home, but not for long. He had a new boyfriend. “He was so disrespectful. So my mother told me to leave with him,” he said.

Today, Cabrera said, his mother has found a way to accept him. “I love my mom, and she felt so bad,” he said. “I told her, ‘Thank you for letting me learn what the world is,’ because a lot of people never get that chance to know what life can give to you. It’s horrible. I wish I had never gone through that.”

Cabrera now lives in Manhattan’s East Village in a supportive housing building for formerly homeless people, created through a partnership between the New York City Department of Housing Preservation Development and nonprofit organizations. Tenants pay one-third of their income in rent. He works part time at a nonprofit that advocates for young LGBT people’s rights but says he doesn’t make enough money to support himself. He often goes to food pantries.

He loves to rap and design clothes, and he makes T-shirts for the New York Gay Pride march. He hopes to go back to school someday.

“I dream to go to school and be a fashion designer,” Cabrera said. “I love having fabric in my hand and tearing it up with scissors. I want to be an entrepreneur and do something with my life.”