Nearly half of America’s homeless women and girls are parents or are about to be parents, a chilling new study has found.

Another 18 percent of homeless young men or boys are fathers themselves, the University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall found in the latest of its research briefs on youth homelessness. In total, people who are 18 to 25 years old and have been homeless in the previous year are parents of some 1.1 million Americans, researchers found.

“This is really like a two-generation problem,” said lead author Amy Dworsky, a Chapin Hall Research Fellow. “It’s not just the young parents that we need to provide the services to, it’s also the children of those parents.”

Among Chapin Hall’s findings:

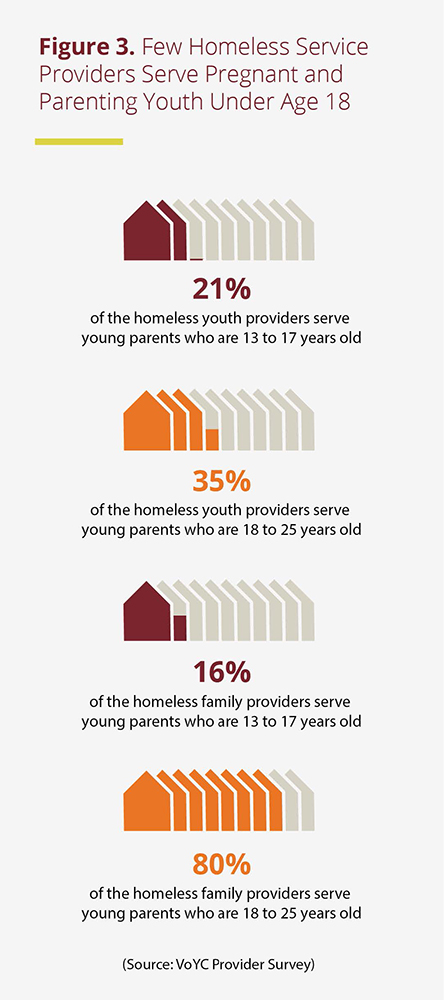

- Relatively few homeless service providers serve minor parents.

- It can be difficult for young families experiencing homelessness to maintain relationships while receiving services.

- Pregnancy and parenthood may increase the risk of youth homelessness.

“Some of these young people are already pregnant or parenting when they become homeless,” Dworsky said. “One of the things that we learned from the interviews is that for some young people, if they become pregnant, that caused considerable conflict in the family or escalated pre-existing conflict. The situation just became so untenable.”

The homeless parenting study is the third in a series by Chapin Hall. The research group wants to create a baseline for longitudinal studies of youth homelessness in the U.S. Previous studies have focused on risk factors of youth homelessness and on the plight of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer youths.

“One of the most striking things we saw when we analyzed the data,” Dworsky said of the new report, “was just the high number of young people who reported that they were pregnant or already pregnant. It really stood out for its prevalence.”

Besides analyzing data, Chapin Hall researchers are also conducting in-depth interviews with hundreds of youths for each of the issue briefs. Among those who contributed to the latest report was Kera Pingree, 21, of Portland, Maine.

‘A million different requirements’

Already a mother when they graduated from high school (Pingree uses the pronouns they and their), Pingree was kicked out of the family home when their mother wearied of Pingree’s depression.

Already a mother when they graduated from high school (Pingree uses the pronouns they and their), Pingree was kicked out of the family home when their mother wearied of Pingree’s depression.

“She said that she just didn’t want me there anymore,” Pingree said. “Maybe she was trying to start a spark, I don’t know.”

Pingree left their little girl, Emma, then 3 years old, at their mother’s home and then couch-surfed for a month before settling on a teen shelter.

“It was really confusing,” Pingree said of their search for a safe place. “I had, like, a bike with a couple of plastic bags with my stuff. I had two backpacks on. I went to the adult place first because it was the only place I knew. They had Wi-Fi and my phone was like 3 percent. I was just trying to find somewhere where I could go.”

The teen shelter wouldn’t let Emma stay, so eventually Pingree moved into a family shelter, where they and Emma spent the next five months.

“I had a to-do list going every day with a million different things,” Pingree said. “There were a lot of people who wanted to help but they had a million different requirements — I had to meet with them, or they needed documentation — and I had to keep my head from spinning off.”

Pingree and Emma moved into the shelter in January, in the midst of another of Maine’s unforgiving winters. Every day, Pingree bundled Emma into double layers, put her in a stroller that they covered in a blanket and then carried the stroller around as they ran their errands, they said.

Now employed and with a stable home and two jobs (and a newborn, Yvonne, who’s 8 months old), Pingree said they read Chapin Hall’s latest findings with shock of recognition and a feeling of relief that finally someone understood what they and Emma had been through.

“My first reaction was that I was not surprised by anything that they found. But I was glad they found them, anyway,” she said.

There are countless young, homeless people “hiding out” and it’s important that researchers — and policymakers — work to find them, Pingree said.

“First of all, remember that we exist. For young parents, there’s a lot of hiding. There’s a culture of fear and distrust in the system. I think it’s completely valid for folks to feel that way. We can’t forget that they exist,” they said. “It feels to me like folks don’t realize how much of a problem it is, and how much power there is in supporting these young folks.”

This story has been updated.