“Paradigms gain their status because they solve problems.”

— Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

“The music spoke, and we responded.”

— DJ Kool Herc

We often talk about “systems change” in youth work, but we rarely slow down to ask what real change actually looks like. One of the most helpful thinkers on this topic is historian and philosopher Thomas Kuhn, who argued that progress doesn’t usually unfold gradually. Instead, we move through paradigm shifts or moments when the old way of understanding no longer fits, and a new model takes its place.

![]()

Kuhn found that:

Kuhn found that:

- Change begins with anomalies — ideas that don’t fit the old model but point toward something better.

- Crisis is part of growth — when old approaches no longer meet new needs.

- Paradigm shifts reorganize what’s possible — replacing the old frame with a more useful one.

Kuhn’s ideas can feel abstract, but hip-hop gives us a grounded way to see them clearly. And it begins with DJ Kool Herc, widely regarded as the founder of hip-hop. In the early 1970s, Herc pioneered the breakbeat style of DJing, extending the instrumental “breaks” in records so dancers could keep moving, and built community-centered parties in the Bronx that became the foundation of the entire culture. If Herc represents the original paradigm of hip-hop (i.e., local, joyful and built on movement and connection), then the genre’s biggest innovations become examples of the anomalies and shifts Kuhn described.

Below are three of Kuhn’s core concepts, each illustrated through how hip-hop evolved from Herc’s foundation.

Anomalies: The moments that don’t fit

Kuhn argued that major change begins with an anomaly, a new idea or approach that doesn’t fit the established model. At first, anomalies can seem like outliers, but they plant the seeds for transformation.

In early hip-hop, DJ Kool Herc’s paradigm centered on celebration, dance and community connection. His parties created joy and belonging at a time when young people desperately needed both.

Then came Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s “The Message” (1982). Flash took Herc’s structure and turned it in a different direction. Instead of reflecting the joy of the party, he described the poverty, pressure, violence and systemic neglect going on in the world outside of it. It didn’t fit the celebratory model. But it reflected lived reality.

This was an anomaly. The paradigm had not changed yet, but a new possibility had appeared.

Paradigm crisis: When the old model isn’t enough

Kuhn believed that once enough anomalies appear the existing paradigm enters crisis. This doesn’t mean collapse; it simply means the old explanation can’t account for everything happening around it.

In hip-hop, this crisis took shape when Public Enemy arrived. They took the honesty of “The Message” and amplified it into a full-scale analysis of policing, media and systemic racism. Their work wasn’t just storytelling, but rather sharp critique intended to educate and mobilize. They pushed hip-hop toward a purpose that Herc’s original model may not have anticipated.

[Related: When positive youth development meets the Native Tongues]

Suddenly, the idea that hip-hop existed only for partying and dancing was no longer big enough. A new purpose was emerging: hip-hop as truth-telling and political engagement. The field expanded because it had to.

This is what crisis looks like: the old frame can’t contain the new reality.

Paradigm shift: A new model takes over

A paradigm shift, in Kuhn’s terms, happens when a new model replaces the old one and becomes the dominant way of understanding the field.

For this, we look again to Herc as the root: hip-hop as local, street-based and community-built.

Then we look to Run-DMC, who represented hip-hop’s cultural and commercial possibilities. They didn’t simply extend Herc’s model, they introduced a new one:

- Their Adidas partnership opened the door for hip-hop fashion as global business.

- Their presence on MTV broke racial barriers that had kept rap off the airwaves.

- Their “Walk This Way” collaboration with Aerosmith expanded the audience for hip-hop dramatically.

- Their arena tours demonstrated that hip-hop could operate at stadium scale.

This wasn’t incremental growth. It was a new paradigm: hip-hop as global culture and commercial force. Herc gave hip-hop its foundation and then Run-DMC and their massive fan base redesigned the structure built upon it.

Why this matters for people who work with youth

I assume that you aren’t reading this to learn about philosophy or music history. You’re probably reading it because many who work with young people are trying to understand change. More specifically, how to support it, how to recognize it and how to help create it.

Right now in youth work, I see several emerging and encouraging anomalies that may signal the next paradigm:

- Schools and afterschool programs are beginning to collaborate more intentionally, creating 360° support around young people rather than operating in silos. This stands in contrast to the long-standing paradigm where schools focused narrowly on academics and afterschool programs were treated as optional add-ons, often working with different staff, goals and communication systems. The new coordination doesn’t fit that old model and may signal an emerging shift toward integrated youth ecosystems.

- Youth voice is moving from “input” to genuine partnership, challenging long-standing adult-driven decision-making models. For decades, the dominant paradigm positioned young people as participants to be guided and consulted “when appropriate,” with adults designing programs, policies and priorities on their behalf. The growing number of youth advisory boards, youth-led research teams and shared decision-making structures represents a clear break from that tradition and may point toward a future where youth are true co-creators.

- Mental health supports are being integrated into everyday youth spaces, not reserved for moments of crisis. This contrasts sharply with the conventional paradigm in which mental health was addressed only when young people were in acute distress and required referral to outside specialists. Embedding wellness practices into classrooms, afterschool programs and community settings departs from that crisis-response model and may indicate a shift toward proactive, holistic mental health support.

These ideas may seem small, scattered or inconsistent, but that’s exactly what anomalies look like in the beginning. They don’t fully fit the old framework, but they signal the edges of a new one.

Hip-hop shows us that the next paradigm rarely starts in the center. It begins at the margins: a block party, in a small studio, in the voices doing something that doesn’t quite match what came before.

If we can learn to recognize those moments in our youth systems and nurture them we may help create the next shift.

And if we didn’t know that before…well, now we do.

***

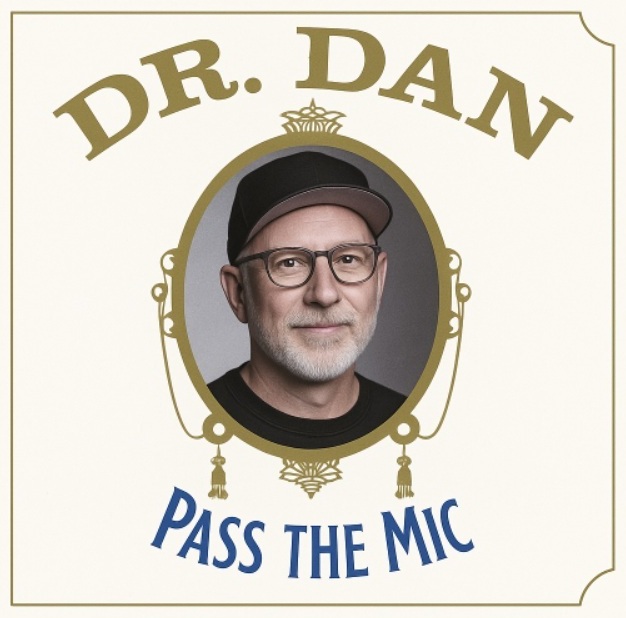

Pass the mic: Where hip-hop meets human development. Each month, Daniel Warren, Ph.D., will bring scholars and rappers into dialogue to spark new ways of seeing youth, culture and change. Previous pieces in series:

When positive youth development meets the Native Tongues | Biggie through Bronfenbrenner’s Eyes

Daniel Warren is director of youth development and education at Fluent Research. He holds a B.S. in psychology from Northeastern University and a Ph.D. in human development and child study from Tufts University.