This story was originally published by ProPublica.

For nearly a year, Melanie Call struggled to balance working from home full time with caring for her new baby.

Her job as a project manager for a Salt Lake City health care staffing agency required spending hours in video meetings. If her son was awake, she would turn off her camera. When he woke from a nap while she was already occupied in a meeting, she would feel her guilt grow as she heard him cry through a baby monitor.

Call, who is married to an architectural designer, had an older daughter in elementary school and a younger daughter already in day care, and wasn’t sure she could afford to send another child.

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Liam Call, 2, throws a tantrum while Melanie Call, 38, puts him in his car seat outside of her mother’s home in Draper, Utah, on December 6, 2023. “Sometimes moms just have to give themselves some grace and breathe through the tantrums,” said Call. “I just try to be patient with him.”

Having two children in day care would have consumed nearly 20% of her family’s take-home pay, despite her and her husband making six figures combined. Eventually, she put her son on three waiting lists for day care, but before she could find an opening she reached a breaking point and quit her job. A week later, a day care slot opened up.

“I wanted to work but I just didn’t have enough support,” Call said, describing a “layer cake” of challenges: unaffordable and scarce day care and a workplace that was unwilling to accommodate her circumstances as the mother of three young children.

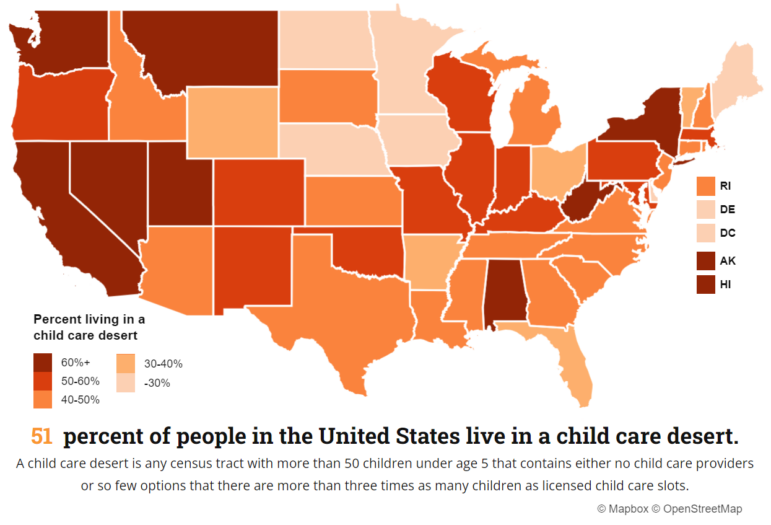

Utah, with the nation’s highest percentage of children, has faced a decades-long day care crisis. A larger proportion of Utahans live in areas with few or no licensed child care facilities than in any other state, according to a 2018 analysis of census and licensing data by the left-leaning Center for American Progress, the most recent available. A 2020 report by the state’s Office of Child Care found that Utah’s child care capacity was meeting only 35% of its needs.

Federal pandemic relief funding eased the shortage by helping day care owners cover basic expenses like rent and supplies. After Utah received nearly $574 million in aid during 2020 and 2021, the number of licensed child care slots rose by about 30% from March 2020 to August 2023, according to a report by Voices for Utah Children, an advocacy group. The funding also provided child care subsidies to more lower-income families.

But on September 30 most of that federal funding expired, and Utah legislators have rejected proposals to replace it with state dollars — continuing decades of local opposition to expanding and improving outside-of-home care for young children.

Nearly half of licensed programs could close in Utah

The result, according to working parents and child care providers who spoke to ProPublica, is that a state billing itself as the most “family-friendly” in the nation does too little to ensure that care for children of working parents is accessible and affordable.

The child care providers who spoke to ProPublica said the federal funding kept them in business. Now, with the loss of that money, most said they are being forced to raise their rates or let employees go and care for fewer kids while working longer hours for less pay. Some said they are considering closing their doors and changing careers.

An estimate by the Century Foundation, another left-leaning think tank, projected that Utah is one of six states where nearly half of licensed programs could close.

“I see teachers burned out. I see parents leaving the workforce,” said Brigette Weier, an organizer with Utah Care for Kids who works with Voices for Utah Children. “I see parents sobbing when they find child care. I see parents sobbing when they can’t find child care.”

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

The Utah State Capitol is seen in Salt Lake City, Utah, on December 7, 2023.

“Why do we have to choose between having our careers and raising children? Why can’t we have both?”

Melanie Call, previously working Utah parent

Legislatures in other conservative states have provided their own taxpayer money to help compensate for the loss of federal funding. The Utah Legislature, which convenes this month, has a long track record of opposing such assistance.

ProPublica spoke to three dozen people involved in child care in Utah, including parents, child care providers, policymakers and advocates, about the impact of the funding loss. They attributed lawmakers’ resistance to subsidizing child care, in part, to the makeup of the Legislature — 74% of lawmakers were male as of 2023, and an even bigger share are Republicans. Some older lawmakers haven’t dealt with the current economic and caregiving realities confronting young parents, they said, or view child care as a personal, not societal, problem that shouldn’t require government intervention.

Johnny Anderson, a Republican state legislator from 2009 to 2016 and president of Utah’s largest private child care provider, ABC Great Beginnings, said among lawmakers there’s still that sense that child care “is a choice rather than a necessity.” And conservative legislators view providing state funding “as a way to manipulate the free market,” he said. “But we all know that child care is a failed market: Child care is not able to charge enough tuition to cover the costs” of providing quality care.

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

The Brigham City Utah Temple is seen near S Main Street in Brigham City, Utah, on December 7, 2023.

In addition, those who spoke to ProPublica noted that most Utah state lawmakers are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which emphasizes women’s role as the primary caregivers for their children and has historically discouraged mothers from working outside the home. This religious and cultural influence, while typically going unspoken in public debates, creates added resistance to state child care assistance, some advocates told ProPublica.

Call, who is a member of the church, said she was taught that it is her divine duty to care for her children. That adds to the pressure for her to stay home with them. But she doesn’t believe it prevents her from being ambitious in pursuit of a career. She said she would like to see state and church leaders acknowledge that.

“Why do we have to choose between having our careers and raising children?” she asked. “Why can’t we have both?”

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Audrey Call, 12, left, puts away dishes as her mother Melanie Call, 38, prepares hot chocolate for Amelia, 5, and Liam Call, 2, after they arrive at home from school in Sandy, Utah, on December 6, 2023. Call, who is unemployed and unable to afford childcare, spends most of her day caring for her three children.

“A gut punch for child care”

Parents placing their kids in day care can choose in-home care, which typically involves smaller groups of children at a provider’s residence; or center-based care, larger group settings where classrooms sometimes separate children by age. Regulations dictate the number of staff per child based on the age group. Because of the demands of caring for infants and younger children, the ratio of caregivers to children is lower for those ages.

Utah child care operators and workers, who are overwhelmingly women, have for years been pinched by uncertain enrollment and low pay, causing perpetual staffing shortages. People who work in child care in Utah are about four times more likely to report having multiple jobs than those in the overall workforce, according to a 2022 survey of 10,000 child care workers by the state’s Department of Workforce Services. Benefits such as health insurance and paid sick leave are not available to most child care workers in the state.

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Aleatha Child, 29, talks with children during snack time at her home daycare in Brigham City, Utah, on December 7, 2023. “If I had to close, if I couldn’t sustain a stable income, I would be really depressed,” said Child, who had to cut her full-time staff. “I fight for these families. I love these kids as if they were my own kids. It’s not an easy job, but it’s a rewarding job.”

“They don’t fight for us, our Legislature. They don’t have my back. We do not have a voice … in Utah”

Annette Wasden, in-home care provider, planning to close business and leave Utah

Labor costs make up a majority of a day care’s expenses. But it’s impossible for providers in the U.S. to charge enough tuition to pay significantly higher wages while keeping child care affordable without government aid, according to a 2017 U.S. Department of the Treasury report on the economics of child care.

Federal policymakers have attempted to address this with subsidies for lower-income families. In Utah, a family of three qualifies for a subsidy if their annual household income is less than $71,940.

Last year, the state child care office raised the income limits to receive a subsidy. If a family receives a state subsidy, their co-payment is capped at 7% of their household income. If the family is slightly above the income requirements and doesn’t receive a subsidy, they could spend as much as 38% of their income on child care, according to a 2020 Utah Office of Child Care report.

In 2022, the average pay for child care workers in the state was $13.10 an hour, compared to the national average of $14.22, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. To receive the federal pandemic grants, providers were required to pay a majority of their employees at least $15 an hour.

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Conner Jones, 4, plays with a toy cash register at Sharon Miller’s Early Care and Education Program in Helper, Utah, on December 5, 2023.

Annette Wasden, an in-home care provider in Clinton, north of Salt Lake City, said she used the grants to hire two additional employees, who she can no longer afford. She plans to close her day care and leave the state. Wasden, a second-generation child care provider, said the work is her passion but she doesn’t feel respected.

“They don’t fight for us, our Legislature. They don’t have my back,” she said. “We do not have a voice in this line of business, or even in Utah.”

In September, Anderson, the ABC Great Beginnings president and former legislator, sent two letters to his customers. One detailed why the company needed to raise its rates by an average of about 5% after the relief funding ended. The other urged parents to contact their state representatives and “tell them that the Legislature needs to provide additional and adequate funding for child care” to avoid program closures and tuition increases.

ABC Great Beginnings’ payroll costs rose by about 50% after receiving the stabilization grants, according to the letter. Recently, Anderson has also seen vacancies in his classrooms, which could be due to the state’s expansion of all-day kindergarten. Anderson also wonders if raising rates has led families to turn to child care that is unpaid or unregulated, which is difficult to track. Enrollment at his 15 Salt Lake City area centers has declined 6% compared to last year.

“It’s a gut punch for child care,” he said of the funding loss. But any state response would require families and teachers to engage in “a humongous campaign to make legislators more aware of it.”

“Most of us would qualify for food stamps”

As director of the Utah Women & Leadership Project at Utah State University, Susan Madsen has traveled around Utah over the past two years asking hundreds of women and girls about their biggest concerns. Child care is “an issue in every single county,” she said, but “rural counties are really struggling.”

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services considers child care to be affordable if it consumes no more than 7% of a family’s income. An October report by Voices for Utah Children found some counties where families spend more than 17% of their income on child care — all but one of them rural. And licensed child care is scarce in rural areas of the state, with capacity for only 36% of the children under six whose parents work.

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

A mountain view is seen during sunset in rural downtown Helper, Utah, on December 5, 2023.

Aleatha Child runs a home-based day care in northern Utah’s Box Elder County, which has one of the worst shortages of licensed child care spots in the state, according to the Voices for Utah Children analysis. The bright blue walls of her basement classroom are full of art by the children she cares for, along with notes bearing inspirational messages: “We are all different! But together we are strong and look beautiful” and “You are enough just as you are.”

“Every penny I make is just to survive … We’ve always just taken whatever we can get and just keep going.”

Sharon Miller, Provider of the Year 2019

She said the federal grants paid for an additional staffer, as well as supplies and toys and replacing aging carpet in the classroom.

As the funding ended, Child considered closing her day care and working at her son’s elementary school, either in the cafeteria or as a teacher’s assistant. She’d still be around children, she reasoned. But for now she is keeping her day care open, raising her rates and cutting expenses where she can. She said she’s begun selling blood plasma to make ends meet.

“It hurts me thinking about” closing, she said. “I have so much joy with these children that I have in my program. I have such a strong bond and connection with their families, with them.”

Sharon Miller, the only day care provider in the central Utah town of Helper, has reduced her hours and enrollment since the grants ended. The money had allowed Miller to hire help, but she recently returned to working alone.

“Every penny I make is just to survive,” said Miller, who in 2019 was named a Provider of the Year by the Professional Family Childcare Association of Utah. Miller, who has provided day care since 1999, said most years she doesn’t make a profit, even when she has gone without a salary. In 2019, before the stabilization grants arrived, she reported a $17,000 loss from her business, according to tax returns she shared with ProPublica.

[Related: Daycare owners and parents say they are at a breaking point as federal relief funds end]

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Casey Jones, 1, left, Alice Otto, 2, Sharon Miller, 53, and 8-month-old Kenneth Otto cuddle after Alice approached them in tears at Sharon’s Early Care and Education Program in Helper, Utah, on December 5, 2023. “It’s important that the kids learn how to communicate. I want to set them up for the real world,” said Miller, who has a total rotation of 16 children between the ages of 0-12. “We work on self-help, communication skills and socialization skills.”

Miller fractured her lower spine in a fall from a ladder in July and wears a back brace during her 10-hour-plus workdays. On a recent afternoon, she watched children as they rode tricycles around her backyard, which she has transformed into a colorful playground with a sandbox, garden, stage for performances and space for creating art projects. The children dropped toys at her feet, but she avoided bending down for them because of the lingering pain in her back.

Miller said she wishes state lawmakers could see firsthand what it takes to provide good child care. Legislators say they support small businesses, she said, but don’t seem to consider that her day care is a small business. House and Senate leadership did not respond to requests for comment.

“We’ve always just taken whatever we can get and just keep going,” she said. “And I think people are to the point where they’re done doing that. It’s really not fair to ask us to keep doing that just because most of us would qualify for food stamps on our incomes.”

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Luna Taylor, 4, left, Elliot Steele, 3, Sharon Miller, 53, and Casey Jones, 1, choose a children’s dance video to watch at Sharon’s Early Care and Education Program in Helper, Utah, on December 5, 2023. who only allows a limited amount of screen time.

“Farmed out”

Some conservative states have stepped in to help child care operators as federal funding dwindles. Alaska set aside an additional $7.5 million for day care owners. Louisiana made its largest investment in more than a decade to its child care subsidy program for lower-income families. North Dakota added $66 million in new funding to its budget for child care.

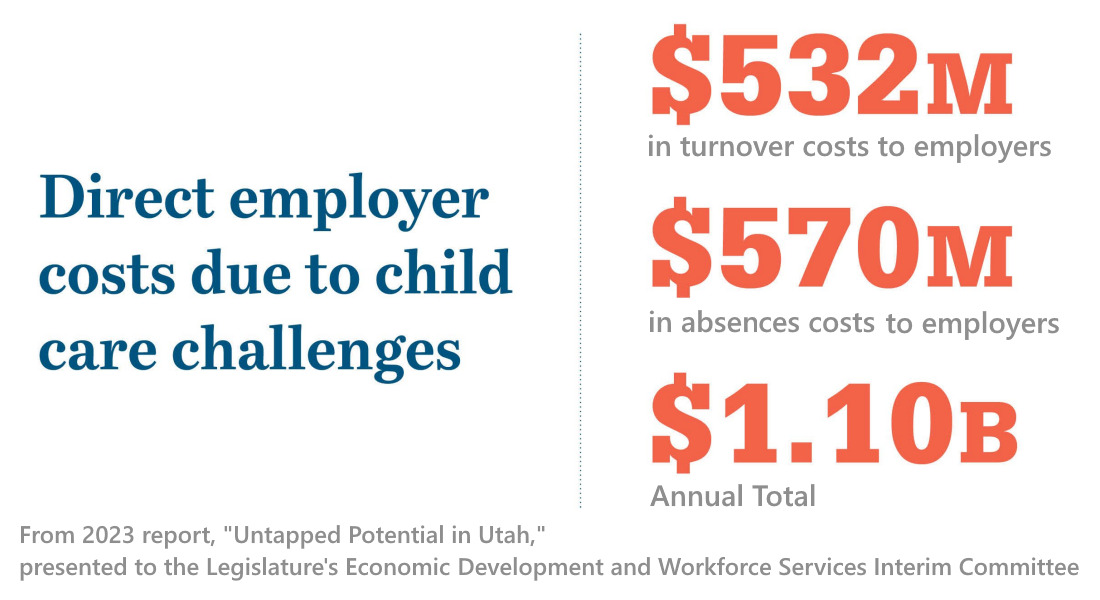

In Utah, state Rep. Andrew Stoddard, a Democrat, last January requested $216 million to pay for a one-year extension of the stabilization grants. He told the Legislature’s Social Services Appropriations Subcommittee that this would “prevent the collapse of the system” and cited figures from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation estimating the child care shortage costs Utah’s economy $1.36 billion a year. “That amount that we’re losing in tax revenue is more than this ask,” he told the committee.

“… the Legislature shouldn’t incentivize “farming” out children.”

Rep. Mark Strong, (Rep-Utah)

The committee’s chair at the time, Sen. Jacob L. Anderegg, a Republican, said, “If I’m a betting man I’d give you almost next to no odds of getting $216 million.” Anderegg instead recommended a “more balanced” approach — a $5 million request — that went nowhere.

Indeed, even modest child care measures have consistently faced resistance.

In 2020, Rep. Suzanne Harrison, a Democrat, proposed a tax credit for businesses that subsidized or provided licensed child care for employees. She argued the bill would help businesses attract workers and increase access to care.

During a hearing, Rep. Mark Strong, a Republican, questioned whether it was the government’s role to provide such assistance. “I struggle with taxing people, all people, some to cover these for everyone.” Strong, who is a sales representative, acknowledged his wife had been able to stay home and care for their six children.

“It was really disappointing that a modest tax credit to support working families was not more favorably considered,” Harrison, now a member of the Salt Lake County Council, told ProPublica. She didn’t propose any child care legislation during the remainder of her term, which ended in 2022.

Last summer, child care advocates presented to the Legislature’s Economic Development and Workforce Services Interim Committee a report on the economic impact of the state’s lack of affordable child care, the same report Stoddard cited in his funding request.

Strong, a member of the committee, said in response that no one can “provide parenthood like a parent” and that the Legislature shouldn’t incentivize “farming” out children. “What is the ongoing economic impact of a child that is raised in a stable safe home by parents, not being farmed out?” he asked. Strong did not respond to a list of questions from ProPublica.

Advocates said Strong reflects the attitudes of some in the Legislature who view bolstering child care as contributing to the erosion of families.

Rep. Susan Pulsipher, a Republican, sponsored and helped pass legislation in 2022 to increase the number of children an unlicensed provider is allowed to care for. The change was criticized by some child care providers as unsafe.

Pulsipher also sponsored another successful piece of legislation that established a tax credit of $1,000 for families with a child between the ages of one to three. Pulsipher, a homemaker with 20 grandchildren, said the credit allows families to pay for the kind of child care they want, whether at home, at a center or at an in-home provider. But because the tax credit is nonrefundable, meaning it can only be used if a family owes taxes, and limited to lower-income families, only an estimated 1.4% of state taxpayers would benefit from it, according to an analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

“I don’t think it’s enough,” Pulsipher acknowledged. “But it’s a start. And we need to start and we need to keep going.”

“Her place is in the home”

Some child care operators and policy advocates say the teachings of Mormon church leaders contribute to lawmakers’ reluctance to support child care. Forty-two percent of Utah adults consider themselves members of the faith, according to a recent study.

The church declined to comment for this story.

Colleen McDannell, a professor of religious studies at the University of Utah, said church leaders have long encouraged women to pursue an education but have not dealt with the notion that women in the church are transitioning from having part-time jobs to having careers.

While Utah ranks last in the nation for the share of children under six with both parents in the labor force, the percentage of mothers who are working has in the past five years increased to 64%.

“One of the ways that the LDS church deals with difficult things is just to not talk about it — it just disappears from the public conversation,” McDannell said. “So if you add that, along with the notion of a red, Republican individuality — that if you want to work, that’s fine, you should just go and figure out how to do it yourself — that means you’re going to have a difficult time with child care.”

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

The Brigham City Utah Temple is seen from a neighborhood in Brigham City, Utah, on December 7, 2023.

Spencer W. Kimball, the church president from 1973 to 1985, preached that husbands should support the family and “only in an emergency” should wives work. “Her place is in the home, to build the home into a heaven of delight,” said Kimball. He attributed the rise in divorce rates to women increasingly working outside of the home.

His successor as church president, Ezra Taft Benson, gave a 1987 address in which he said that “among the greatest concerns in our society are the millions of latchkey children who come home daily to empty houses unsupervised by working parents.” Benson also encouraged young couples to not delay having children and reiterated that a “mother’s calling is in the home, not in the marketplace.”

In 1995, as the church became an increasingly global organization, its leadership issued “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” which summarized teachings on gender roles, among other things. It called for egalitarian relationships in the home but designated women as “primarily responsible for the nurture of their children.”

The percentage of Utah mothers who are working — in the past five years — has increased to 64%.

Today, there’s a “gentle recognition” among church leadership that many women must work, said Patrick Mason, a Utah State University professor specializing in Mormon history: “It’s not really a retreat from the ideal; it’s just kind of an acknowledgement of economic realities.” Yet, he added, “the church has never repudiated those former views — you won’t find statements like that. So it’s marked mostly from an argument from silence.”

The result, Mason said, is that older lawmakers may hold on to earlier teachings and “create policies that incentivize the ability of mothers or possibly fathers, but primarily mothers to stay home with the kids.” The church declined to comment for this story.

Rep. Ashlee Matthews, a Democrat who campaigned on improving child care, is a mother of two young boys and an office manager. She said she has had “hard” conversations with legislative colleagues, explaining that the economic realities have changed since older lawmakers raised their kids. Most households need two incomes, she tells them, and child care isn’t a “mom” issue, it’s a parent issue.

Advocates have succeeded with local approaches in places like Park City, where the City Council recently voted to add $1 million to its budget for early childhood education and child care, including scholarships for lower-income families. Park City launched the assistance program this year. It might be the only city in Utah to provide such funding, said Kristen Schulz, the director of the Early Childhood Alliance at the Park City Community Foundation.

In arguing for the proposal, Schulz said, she framed it as an investment in children rather than a city expenditure: The money would help the economy and community and increase equality. “Depending on what people are really concerned about, I feel like there’s a lot of good arguments,” she said.

“Life is about choices”

During its 2024 session, the Utah Legislature will consider a variety of proposals to boost public investment in child care. One would extend the expiring stabilization grants for two years at 50% of the federal level, at a cost of $120 million annually. Another would expand Pulsipher’s child tax credit. And yet another, backed by Sen. Luz Escamilla, the Democratic minority leader, would create a pilot program to retrofit vacant state buildings into child care facilities.

Gov. Spencer Cox’s proposed budget supports Escamilla’s plan and expansion of the tax credit.

Escamilla said that for many years ”child care wasn’t even part of the conversation in the Legislature” but the issue has gained some traction as more female lawmakers have been elected.

[Related: Home-based childcare is a dying business. Here’s why.]

Call, who left the workforce because of her inability to find affordable child care, said the year since then has been “healing.” She’s looking to start a business and has been involved with organizations advocating for increased support of Utah’s working mothers, including subsidies to lower the cost of child care. She has contacted lawmakers and become more outspoken at church about women’s dual roles as caregivers and professionals.

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Melanie Call, 38, sits in disappointment after congressman Blake Moore did not show up to their scheduled zoom call about the Child Tax Credit and accessible childcare options for parents in Provo, Utah, on December 6, 2023. “It’s frustrating, but like I said, I’m not going anywhere,” said Call, who met with the congressman’s staffer instead. “I will take my business trade of 20 years and make stuff happen.”

Last October, Call, with her toddler son and then-12-year-old daughter, traveled to the state Capitol for a “stroller rally” in support of child care. From a podium in the Hall of Governors, she shared her story about leaving the workforce.

“Life is about choices,” she said. “So we must ask ourselves: What choices are we providing to Utah’s women, parents and caregivers?”

***

Nicole Santa Cruz is a Phoenix-based ProPublica reporter focusing on investigating the impact of inequities on marginalized communities in the Southwest. Previously she reported for the Los Angeles Times for 12 years as a staff writer. She was also the lead reporter on the Times’ Homicide Report, a groundbreaking public service project that documents the lives of every homicide victim in Los Angeles County.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.