This story was originally published by ProPublica.

If you talk to town officials — the supervisor, the elected board members, the chief of police — they will tell you that mayhem has arrived in Pleasantville.

A quiet, leafy village in the town of Mount Pleasant, less than 20 miles north of New York City, Pleasantville feels like the movie-set version of an affluent Northeastern suburb. Five-bedroom homes overlook tranquil cul-de-sacs and freshly mowed lawns. Kids really do ride their bikes in the street after school. The village is less than two square miles, so if you hit an errant ball at the Pleasantville Tennis Club, you could almost smack a neighbor teeing off at the Pleasantville Country Club.

“Bucolic Pleasantville, N.Y., is seeing a showdown between leaders of a century-old children’s residence unequipped to treat acute mental health challenges and locals tired of troubled young people disturbing the peace. What happens to the kids?”

For more than 100 years, the village has coexisted, more or less peacefully, with the Pleasantville Cottage Campus — a residential program that, in its current iteration, houses about 160 young people with behavioral challenges. Nearly all its residents are in foster care; most are from New York City. While Pleasantville is 87% white, almost all of the youth on the campus are Black or Latino. The majority have histories of severe trauma, according to staff at JCCA, the nonprofit foster care provider that runs the campus. Many were sexually trafficked. Some had multiple psychiatric hospitalizations or lived in five, six or seven foster homes before landing here.

Like other residential foster care programs (there are just over 200 “congregate care” facilities in New York state, with about 3,600 beds), the Pleasantville campus has periodically been the target of complaints from local residents. Young people leave the grounds without permission. They get into fights and shoplift from stores, neighbors and police say.

But during the past several years, those complaints have grown incendiary, erupting last summer into a bitter public battle that threatens to shut the campus down.

The escalating tensions have been well documented in town Facebook groups and the local paper: In 2022, neighbors were aghast when a resident from the Pleasantville campus stole a chicken from a coop in a nearby backyard and bit its head off. Later that year, a video made the rounds of a young man from the campus standing shirtless in front of a car, blocking the road. When the driver demanded that he move, he begged her to kill him.

Meanwhile, the frequency with which local police are called out to the campus climbed from several times a month in 2018 to several times each week in early 2023, according to Mount Pleasant Police Department records. Most of the contact between JCCA and the police involves missing persons: young people who run away from the campus, usually returning on their own after a few days. But disastrous things happen, too. In 2019, for instance, a young man on campus was paralyzed after being restrained by program staff and died a year later, according to Mount Pleasant Police Chief Paul Oliva. (JCCA officials declined to comment on the incident, citing privacy concerns.) Residents also regularly get into fights, break windows, assault staff and threaten to hurt themselves or someone else, police records show.

Town leaders place the blame squarely on JCCA, which has run the campus since 1940, for losing control of its kids.

Natalie Keyssar/For ProPublica

The Edenwald School is one of two schools on the Pleasantville Cottage Campus.

But, in fact, what’s been happening in Pleasantville in recent years is an extreme and very public version of something that’s occurring at foster care programs across New York state, an investigation by THE CITY and ProPublica found: Government child welfare authorities are placing kids with acute mental health challenges on campuses that are ill-equipped to handle them — largely because there’s nowhere else for them to go.

State leaders promised to expand young people’s access to mental health services.

Now, families are struggling to get care for youth in crisis.

As THE CITY and ProPublica have reported, New York has shut down one-third of its beds for youth in state-run psychiatric hospitals since 2014 under a cost-capping “transformation plan” rolled out by former Gov. Andrew Cuomo. The state has also greenlit the closure of more than half of the beds in residential mental health programs during the past decade — all while failing to deliver on promises to expand home- and community-based mental health services to hundreds of thousands of young people. Suicidal foster children sit for months on waitlists for therapy and home-based treatment they are entitled to by law.

Among the consequences: The shortage of mental health care is creating chaos at foster care programs like the Pleasantville campus.

Since the Cuomo reform, the Pleasantville campus has had between 16 and 20 residents at a time with very aggressive or self-destructive behaviors, which is beyond the program’s capacity to manage, said Trevor John, JCCA’s senior vice president of campus services. That number used to be just two or three, he said.

Natalie Keyssar/For ProPublica

Trevor John, senior vice president of campus services at JCCA, the organization that runs the Pleasantville Cottage Campus

“We’re equipped to handle behavioral problems — that’s what we’re for,” John said. But with the shutdown of psychiatric beds, kids are frequently discharged to the campus from hospitals before they’re stable, he said.

(JCCA officials said they had brought the young man who killed the chicken to an emergency room twice shortly before the incident happened, but ER staff sent him away without admitting or even evaluating him.)

“There are not good options” for foster youth with acute mental health challenges

Once kids are placed on campuses, it’s very hard for facilities to move them off. Program staff can submit a “15-day notice” asking foster care authorities to find a new placement for a child who needs a different setting, said William Gettman, the CEO of Northern Rivers, a social service agency in upstate New York that has seen a similar influx of youth with acute mental health challenges. But he said the process often takes six to nine months. “The system is in crisis,” Gettman said.

When foster care programs can’t manage residents’ needs, there are “more AWOLs, more assaults on other children and staff, more suicidal and self-harming behaviors,” said Maria Cristalli, the president of Hillside, which runs residential programs in central and western New York.

New York’s foster care programs have had serious problems since before Cuomo began downsizing state psychiatric facilities. A January 2023 report by the advocacy group Children’s Rights described group homes and foster care campuses as “punitive, carceral, isolating, and dehumanizing,” citing former foster youth who said they lived in fear of violence from staff and other residents. (The report did not name individual programs or agencies.)

Add in more chaotic environments, with more fights and more running away, and foster care programs become a pipeline directly to the juvenile justice system for some youth.

Meanwhile, those with the most difficult behaviors — often the ones who’ve experienced the most extraordinary trauma — get pushed into a growing cohort of what the foster care system calls “hard to place” youth: children nobody wants. Foster care providers say they can’t handle them. Mental health programs are full or have insurmountable barriers to getting in. And at least in Pleasantville, the neighbors want them gone yesterday.

In July, Mount Pleasant officials held a press conference demanding that New York state shut the Pleasantville campus down. During the following three months, state child welfare officials granted JCCA’s request to remove 12 residents who staff contended were too unstable for the Pleasantville campus. The move was a win for town leaders, and it took pressure off JCCA, where incidents on campus have dropped sharply since the residents were moved.

Natalie Keyssar/For ProPublica

Downtown Pleasantville

Natalie Keyssar,/For ProPublica

A neighborhood of Pleasantville adjacent to the campus.

But shuffling 12 residents around does not change the fact that “there are not good options” for foster youth with acute mental health challenges, said Ronald Richter, JCCA’s CEO and the former head of New York City’s child welfare administration. The systemic problem “is not solved,” he said.

In fact, only four of the 12 ended up in beds in mental health programs. Some of the others were sent to different foster care campuses or to a temporary shelter for foster children in New York City. And three are now in either the criminal or juvenile justice systems.

“That’s not a positive outcome,” Richter said.

Karen Male, a spokesperson for the state Office of Children and Family Services, which oversees New York’s foster care agencies, wrote in an email: “OCFS continues to work closely with JCCA to support the agency in effectively providing comprehensive, supportive programming for youth in foster care.”

Male added: “The health and safety of these young people, as well as that of the surrounding community, remain a top priority for our agency.”

But if officials hoped that moving the 12 youth would make town leaders back off from their campaign to shut down the Pleasantville campus, it seems unlikely to pan out that way. “Let it be known, we are still watching and still demanding accountability of this facility at every turn,” Mount Pleasant Supervisor Carl Fulgenzi wrote in an October memo posted on Facebook. “Our substantiated facts and statistics continue to overwhelmingly confirm that the situation at JCCA is worsening and wholly unsafe.”

Therapy at Pleasantville

It’s 4 p.m. on a Tuesday, and 16 teenage girls sit on vinyl-covered sofas in a common room on the Pleasantville campus. A few hug teddy bears on their laps. Two pass a watermelon-flavored lip gloss back and forth. Around them, paper butterflies and unicorns hang from baby pink walls, along with inspirational sayings like “Take time to be kind” and “Be your own kind of beautiful.” The TV is behind plexiglass so that no one can smash it.

At this meeting, the girls’ assignment is to discuss emotional regulation: essentially, how do you do the opposite of the destructive thing you really, really feel like doing? They take turns, offering examples of times they were angry or depressed: “When I went into foster care and my mom didn’t fight to get me back.” “When my dad died.” “When I wasn’t allowed to see my father for five years and my mom kept telling me it was my fault.”

What’s most noticeable is the gravitational pull of the counselor who’s running the meeting — a longtime staff member who oversees this particular cottage. Girls drift toward her, sitting on the floor at her feet or standing behind her chair. One, an older girl who came into the room rolling her eyes and muttering, “Oh, hell no,” ends up with her hands on the counselor’s shoulders, chin resting for a few seconds on top of her head.

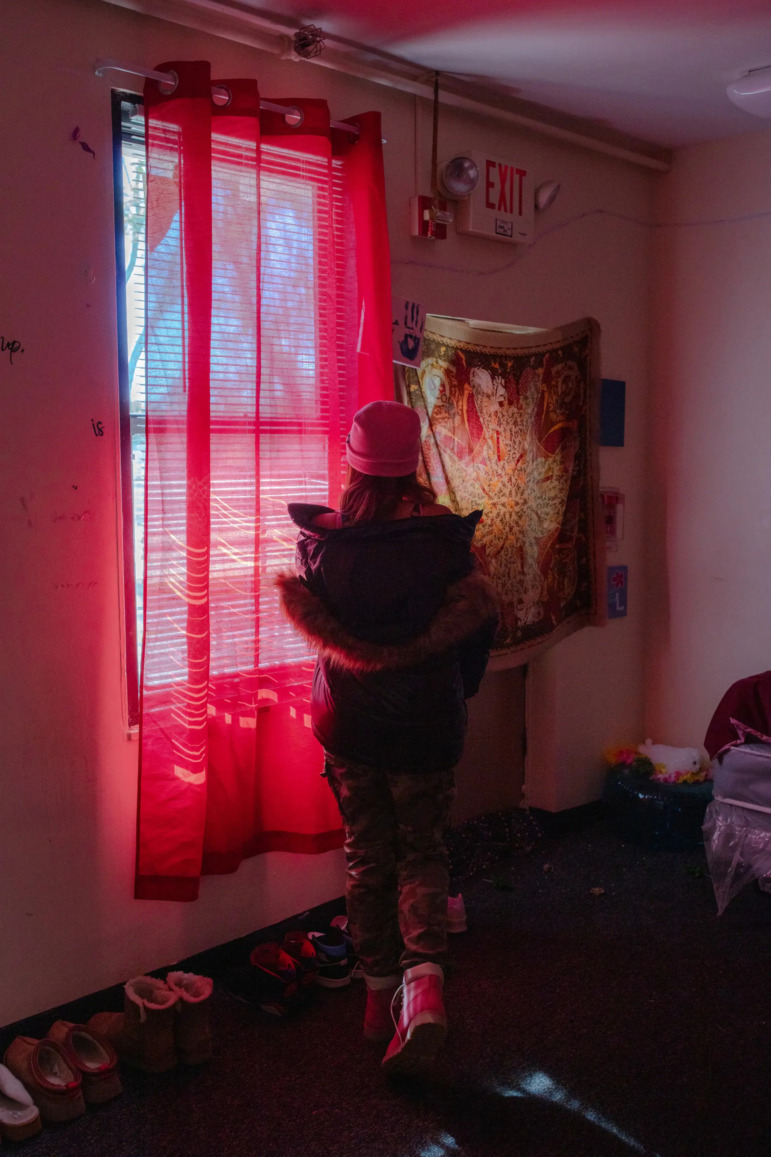

Natalie Keyssar/For ProPublica

A student in her room in one of the cottages.

Meetings like this are designed to teach kids coping skills: how to understand their trauma, identify their triggers and respond in new ways. The experience of being shuffled from place to place — the accumulated sense of being discarded — can drive foster youth to act out with extreme behaviors, said Jeremy Kohomban, president of The Children’s Village, which runs foster care and juvenile justice programs in Dobbs Ferry, a dozen miles south of Pleasantville. Often, he said, those behaviors are ways of “communicating hopelessness and frustration at a system that took them away from their parents and gave them nothing in return.”

Reversing that takes time and trust, foster care providers say: Kids need to see that adults care about them and will stick around. And it can’t happen when staff are overwhelmed by residents in acute crisis.

Part of the challenge stems from limitations on what foster care campuses like Pleasantville are allowed to do. They provide clinical services like therapy and psychiatry, but unlike psychiatric hospitals or residential programs licensed by the state’s mental health department, they cannot lock kids into rooms or physically stop them from walking off of campuses. Nor can they force them to take psychiatric medications or inject them with sedatives or antipsychotics to control their behavior.

Faced with the influx of youth with acute mental health challenges, some foster care providers say those rules need to change — they need to be able to isolate or sedate kids for their own safety.

Shortage of funds; shortage of clinical staff

Almost universally, foster care providers also say they need more money. At the state’s current rates, they can’t attract the clinical staff they need to work with acutely ill youth, said Kathleen Brady-Stepien, the president of the Council of Family and Child Caring Agencies, which represents New York foster care nonprofits in negotiations with the state. Jobs for psychiatrists and social workers often go unfilled for months.

Rich Azzopardi, a spokesperson for Cuomo, wrote that the former governor’s transformation plan, which included psychiatric bed closures, was part of a movement to shift funds into outpatient care. If there are problems with the implementation now, “the current administration and the legislature — who are about to begin negotiations on their third budget together — should address it,” Azzopardi wrote in an email.

Under Gov. Kathy Hochul, New York has allocated $14 million to a program to recruit and retain mental health care workers and has promised to increase outpatient care in communities and schools. But those initiatives don’t touch foster care campuses, where turnover among frontline staff is up to almost 60% each year, Brady-Stepien said.

Hochul’s office declined to comment for this story.

The consequence is that foster care programs increasingly rely on inexperienced, minimally trained employees to manage volatile situations with residents in acute crisis. As a result, foster care providers say, they’re less able to do the most basic part of their job: keeping all their kids safe until they can return to homes.

One teen’s story

On the Pleasantville campus, one of those kids was a 15-year-old named Janemarie.

In 2022, Janemarie was arrested and put on probation for assaulting an older girl. Her adoptive mom, Michelle, was sure that she couldn’t keep Janemarie out of trouble at home, so she asked her school district to find a residential program. (We’re identifying Michelle by her first name and Janemarie by her middle name in order to protect Janemarie’s privacy.)

When Janemarie’s school district suggested the Pleasantville campus, Michelle thought it might finally be the place to give her daughter the help she needed. Janemarie’s biological brothers were attending the day school on the campus, and Michelle thought maybe they could all get therapy together. She also liked that the program had a specialty in working with kids who’d been sexually abused, since she believed that many of Janemarie’s problems started after she was molested at a babysitter’s house when she was 7.

But that was January 2023, when the Pleasantville campus was calling on police to respond to emergencies more than five times a week. “I had no idea what was going on there,” Michelle said.

Natalie Keyssar/For ProPublica

Michelle (right), whose daughter Janemarie lived on the Pleasantville Cottage Campus. and a childhood photo (left) of Janemarie with Michelle.

Almost as soon as she got to the campus, Janemarie felt scared, she told THE CITY and ProPublica. Staff couldn’t control the residents, she said.

At the time, Janemarie told Michelle that girls were threatening to jump her. She started running away — hopping the Metro-North commuter train to New York City, where she’d couch surf or sleep on the street. Even when Janemarie was on the campus, she wasn’t going to school or to her therapy appointments. Staff “will walk in the room and say, ‘OK, it’s time for therapy,’ and she’ll say, ‘Go fuck yourself,’ and they’ll walk away,” Michelle said. Janemarie carved messages like “Fuck my life” into her arms and texted pictures to Michelle.

Then, in June, Janemarie sent Michelle a video that showed three other girls attacking her in her bedroom on the Pleasantville campus and beating her head with a metal pot until she bled. For the duration of the video — about 30 seconds — there was no adult in sight. Janemarie told Michelle that two program counselors were in the building while she was being assaulted, but the girls left the room on their own before anyone intervened. “They’re understaffed and they’re scared of the kids,” Michelle said. “No one wants to jump in and get hurt.”

JCCA declined to comment on Janemarie’s experience, citing privacy and confidentiality concerns, despite the fact that Michelle gave the agency permission to share information about her daughter with THE CITY and ProPublica. In an emailed statement, Richter wrote that under state regulations, campus staff “cannot engage in disciplinary measures, confinement, or utilize forceful restraints. Altercations can occur suddenly, before staff is able to engage or separate people. However, safety measures are taken when risks are known, including placing children in separate cottages and increasing staff coverage and monitoring.”

Citizens take action: Coalition for a Safe Mount Pleasant

Danielle Zaino is the kind of person who shows up for the school drop-off line looking the same as she does for a campaign headshot: two coats of mascara, hair freshly blown out, wedges or heels because she’s only 5-foot-2 and doesn’t like to be towered over. Zaino grew up in Mount Pleasant, meeting her now-husband when she was 10 years old. They moved away for a while, but she wanted to raise her kids back home. “It’s a nice small-town feel,” she said. “You feel safe.”

Zaino is also the kind of person who prides herself on telling the truth and taking care of business, regardless of who gets mad about it. “One of my pet peeves is people complaining about things without doing anything about them,” she said.

Natalie Keyssar/For ProPublica

Mount Pleasant Council Member Danielle Zaino in her home in Valhalla, New York.

So, in 2016, when she heard about trouble with the foster children in town, Zaino called up a friend and started a group called the Coalition for a Safe Mount Pleasant. Cuomo’s transformation plan had been underway for two years, and foster care providers across the state were seeing an increase in residents with acute mental health challenges. At the time, there were two foster care campuses in Mount Pleasant: Three miles down the road from Pleasantville, in a hamlet called Hawthorne, the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services ran a campus with a special unit for kids who’d been commercially sexually exploited. Town residents reported seeing men pull up in black sedans at midnight or 1 a.m. “Barely dressed” girls would run off the campus and jump in, Zaino said. Residents assumed the men were sex traffickers — a suspicion that was later confirmed in federal court, where a ring of adult men were charged with trafficking teen girls, including some from the Jewish Board campus. (The Jewish Board was not implicated in the criminal case.)

Meanwhile, Zaino said, neighbors were seeing a spike in incidents around the Pleasantville campus, including youth breaking into cars and stealing from local stores. People were “afraid to be home alone or to let their kids be home alone. They’re afraid to go into the Mobil, afraid to go into the ShopRite,” Zaino said.

The coalition started organizing local residents, sponsoring public town halls for people to air their complaints and holding regular meetings with JCCA, the Jewish Board and state officials, getting politicians involved. Zaino ran for a seat on the Mount Pleasant town board and won.

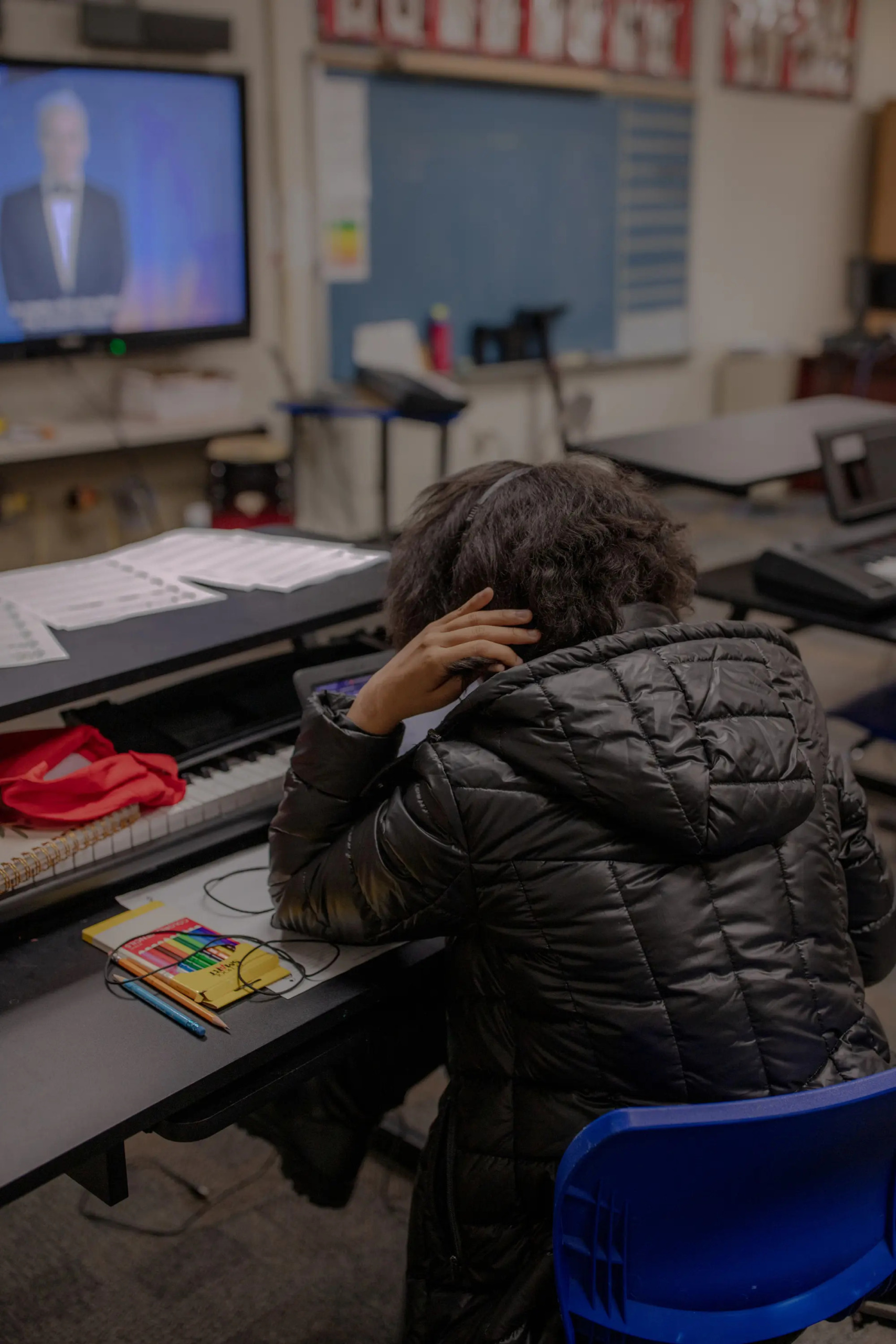

Natalie Keyssar/For ProPublica

A student in music class in the Edenwald School.

But while foster care providers acknowledge that some of the coalition’s concerns are understandable, they say residents have gone too far. People follow foster youth around in stores and videotape them on the street, foster care providers say. Residents call police on kids who are taking a walk or heading to a job in town.

JCCA leaders said kids on campus feel explicitly targeted because of their race. Not infrequently, people in town will call the campus just because someone sees Black kids on the street, even if they have nothing to do with JCCA, John said. Last year, the town started enforcing an ordinance that allows it to fine JCCA $250 every time a resident leaves the campus without supervision. JCCA residents call the fine “the Black tax.”

“For our kids, just being outside is a problem. They too are part of this community. For some kids, this is their only residence,” John said. “When did Mount Pleasant become a sundown town?”

Zaino declined to respond to allegations that kids are targeted based on race. Oliva, the police chief, says that race isn’t a factor in the department’s enforcement. “If we get a call, we investigate it,” he told THE CITY and ProPublica. “If there’s nothing to it, we leave it alone.”

Other Mount Pleasant residents argue that the coalition’s complaints are overblown. “The claim that we are not safe, that’s just not true. This is not a hotbed of crime,” said Francesca Hagadus, who was the first Democrat on record to win a seat on the Mount Pleasant Town Board — which she then lost to Zaino in 2019. “Do the JCCA kids shoplift and get in trouble sometimes? Yeah. But guess what, our high school kids who were born here get in trouble sometimes too. The difference is that they have a home to go to at night.”

Eventually, the Jewish Board shut down its Hawthorne campus. The organization’s leaders never said that the decision was made because of pushback from the town — the agency has invested in programs that keep kids in New York City, closer to their families.

But now, town officials use the closure to threaten JCCA, John said. “They hang it over us like the sword of Damocles: ‘We did it to them. We can do it to you too.’”

If town leaders succeed, John continued, “Where do these kids go? I have youth who are languishing here for a year because their counties don’t have a place to put them. Where would they go?”

What’s the solution?

By the time Janemarie had been on the Pleasantville campus for a few months early last year, Michelle found herself feeling sick every time she heard a text notification. Janemarie would run away for days at a time, sending Michelle oblique, crazy-making messages about where she was and what she was doing.

In June, she took off for Connecticut with a group of girls from the Pleasantville campus. As far as Michelle could tell, they were crashing at an apartment with some grown men. She was pretty sure they were trading sex for money and a place to stay.

“She’s a child who on every level has been failed.”

Michelle, Janemarie’s foster mother

At night, Michelle would have excruciating visions: Janemarie eating a peanut and going into anaphylactic shock without an EpiPen; Janemarie gasping for air with an asthma attack while no one called 911. She couldn’t bring herself to think about the men, though she’d later find a video on Janemarie’s phone of her performing a sex act on what looked like an adult. It made her throw up, so she didn’t look through the phone again.

To Michelle, it felt like a disaster. The whole point of sending Janemarie to Pleasantville was to keep her out of serious trouble. But now, she had “completely unraveled,” Michelle said.

JCCA officials say that in order to focus on young people like Janemarie — those who could, in theory, succeed on their campus — they need more freedom to manage others who are in acute crisis. In 2022, in response to a call for proposals from New York state, JCCA submitted a plan for two “intensive” units on the Pleasantville campus, with eight beds for residents with serious psychiatric challenges and a history of dangerous behavior like running away or being physically or sexually aggressive. If the proposal is approved, staff would be able to lock young people in their units and use injectable sedatives. The model would also come with more staff and more money, via increased reimbursement rates per resident.

JCCA would only use this model in “the most unusual circumstances,” Richter said, to care for residents who would otherwise be eligible for psychiatric hospitals or mental health residences.

[Related story and podcast: ‘Home was never a place’: One woman’s life in WA foster care]

But advocates for foster youth say that putting young people in more restrictive environments is not the answer. Foster care programs are not supposed to be juvenile jails or psychiatric hospitals, said Shereen White, the director of advocacy and policy at Children’s Rights. “How about we look at the quality of care these kids are getting in the first place? Did they get the services they’re entitled to in the community?” she said. “Are they getting proper, comprehensive treatment” on the foster care campus?

What everyone agrees on is that when foster care fails to keep young people safe, there is another system that always has room and can’t turn them away: juvenile justice.

[Related: Unmet needs: Critics cite failures in health care for vulnerable foster children]

In July, Michelle filed a petition in family court, requesting that a judge send Janemarie to a more controlled setting. Janemarie wasn’t safe, she said. But what Janemarie got was not a residential mental health program: The judge sent her to a juvenile lockup, saying that all the fighting, the running away, the refusing to go to school were violations of her probation.

The day Michelle watched Janemarie walk into court in handcuffs, “that was a heartbreak,” she said. “She’s a child who on every level has been failed.”

But there’s also comfort in knowing where Janemarie is and that she can’t run away. “I can sleep at night,” Michelle said. “And maybe she’ll finally get the help she needs. This child suffers so greatly. If they’re smart and they get the right people in there, they’ll see through her antics and behaviors. She needs all systems go, red lights flashing. Hopefully they’ll see that.”

***

Abigail Kramer is an investigative reporter for THE CITY with a focus on education and access to mental health care for New York kids.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.