Thalia Lara

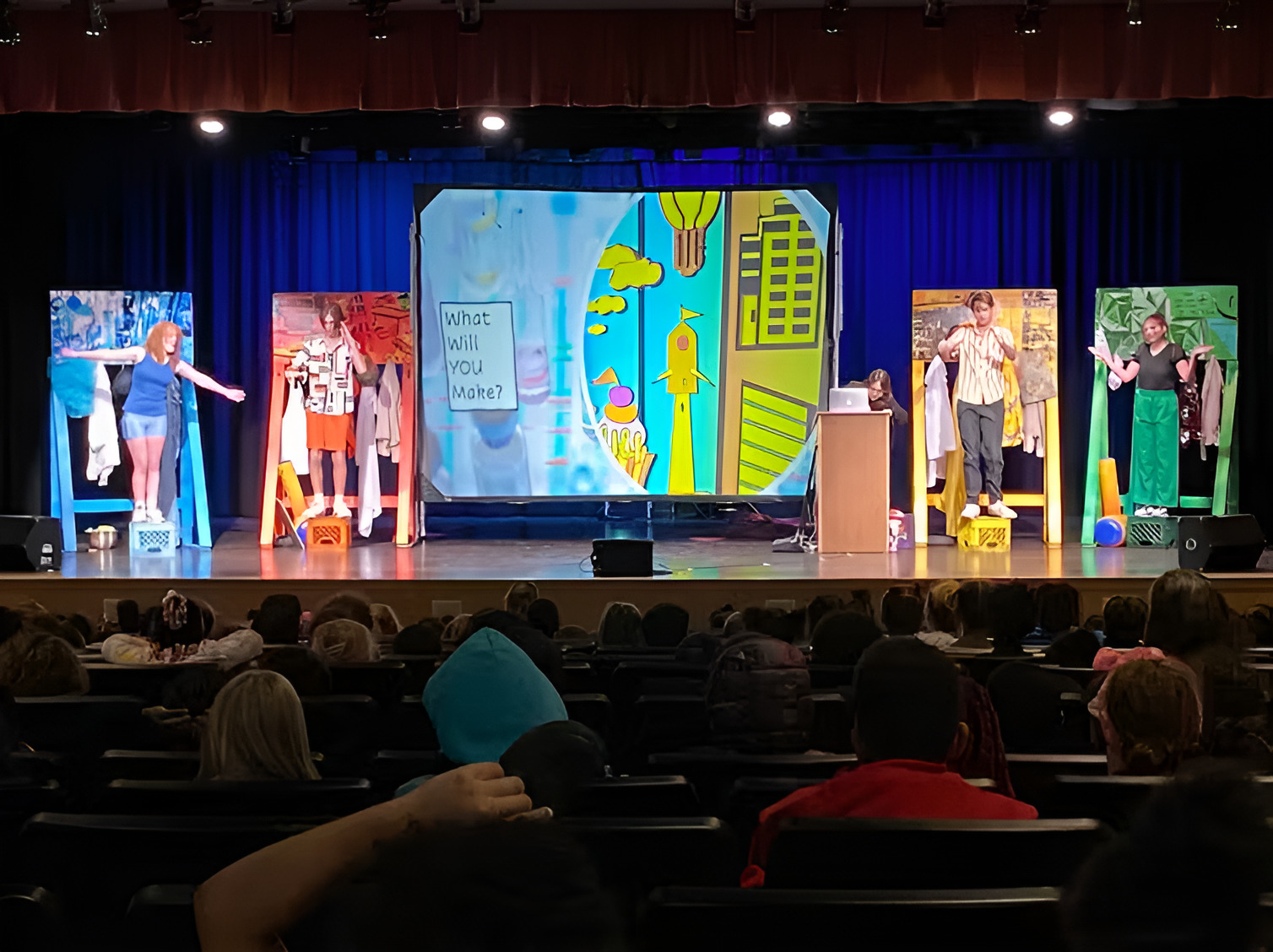

Scenes from ‘The STEAM Plays,’ performed in Michigan schools.

Often, science and art are described as starkly different things. That narrative can start early on, with kids encouraged to pursue a STEM – short for science, technology, engineering and math – education that may or may not include an arts education.

What I learned: Encouraging creative, interdisciplinary thinking matters

As a professor of acting, I’d never thought much about the STEM fields until I received a fellowship to integrate the arts into STEM educational models. I used the opportunity to write and direct a play for elementary schoolers that showed how the arts can improve upon and extend work in STEM fields when properly integrated – but it wasn’t an easy process.

STEM or STEAM?

Whether STEM should be augmented to STEAM – science, technology, engineering, arts and math – with the addition of the arts remains something of a debate.

The origins of STEM education can be traced to as early as the Morrill Act of 1862, which promoted agricultural science and later engineering at land grant universities. In 2001, the National Science Foundation pushed a focus on STEM education in order to make the U.S. more competitive globally.

A Biden-Harris initiative launched in December 2022 called You Belong in STEM offers support of more than US$120 billion for K-12 STEM education until the year 2025. But, starting in 2012, the United States Research Council has explored the idea of a STEAM education.

Researchers have found that when integrated into a STEM education, the arts make space for curiosity and innovation. So why the lack of agreement and consistency around whether it should be STEM or STEAM?

Lots of careers bridge both science and arts, from game design to photography and engineering.

The bias toward emphasizing a STEM education could be driven by the higher future salaries of STEM majors or the significant funding that is connected more to STEM-based research and grants than to the arts. A STEAM education takes more time and is more complex than a traditional STEM educational model.

Or it could simply be that many academics in STEM fields lack the incentive for interdisciplinary work that brings in the arts, and vice versa. In fact, that was exactly the position I was in as an arts-based researcher asked to create something about STEM disciplines that I knew very little about.

Putting on the play

It took me several tries and lots of research to get the script of my STEAM-centered play to its current form.

At first, I made basic discoveries. I learned that there is a debate about whether the arts should be included in a STEM education. I learned that “soft sciences” like psychology are not included in many STEM educational models. I lacked a background in most of the disciplines included in STEM. And I struggled to find a project that inspired me.

… without artistic imagination, STEM students’ big-picture thinking skills can get stifled.

But eventually I began work on five one-act plays, called “The STEAM Plays: Using the Arts to Talk about STEM.” Each focused on a category of STEAM education. I wrote the first draft of the show with a chip on my shoulder, trying to prove that the arts did indeed belong in STEM education.

The tone was defensive and provocative – and not entirely appropriate for the elementary age range I was focused on.

The new, revised version that toured Michigan elementary schools in the Fall of 2023 contains 20 bite-sized comedic scenes and songs that dramatize how the arts are integral to many STEM fields. These include how engineering skills go into designing a celebrity’s evening gown, how bakers need to know some basic chemistry, and how the mathematical algorithms of TikTok find new videos for each user.

In each of the scenes, students can see how artistic imagination and creative thinking expand STEM education.

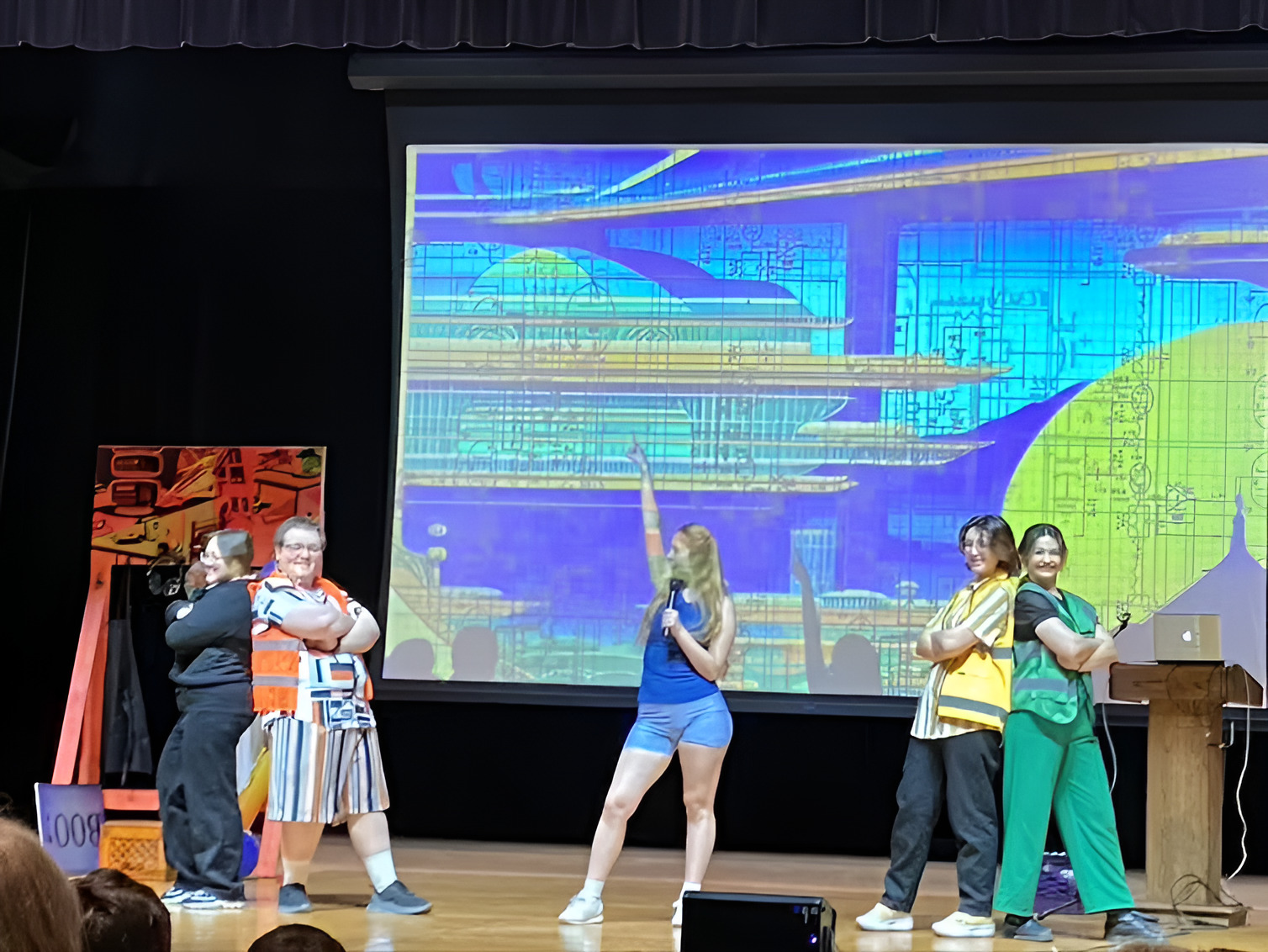

Rob Roznowski

‘The STEAM Plays’ in action. Performers, from left: Alex Spevetz, Marcus Pennington, Zoe Dorst, Cassidy Williams and Olivia Hagar.

Beyond the stage

These themes emerge from a wider scholarly understanding that STEM isn’t done in a creativity vacuum, and stimulating students’ artistic thinking will help them both in the science classroom and the art studio.

One plot point of the show is about an evil genius who views the arts as less important trying to keep the arts out of STEM. He swaps the bodies of a scientist and an actor, as well as an engineer and a creative writer. In each body swap, the STEM professional and the artist recognize how similar their work is. In the final scene, the evil genius tries to switch the bodies of Pythagoras and Taylor Swift, only to realize that music is all about math.

Many teachers have provided rave reviews. “The plays did an excellent job of highlighting the importance and value of arts in our educational system,” one noted. “Students walked away enjoying and having a deeper understanding of how all of the different aspects of STEAM were able to work together collaboratively.

A STEAM education in which students learn soft skills like empathy, collaboration, emotional intelligence and creativity through the arts helps prepare students for the job market. And these discussions aren’t confined only to K-12 education – many research grants encourage interdisciplinary work.

My understanding of the STEM and STEAM debate and my experience writing, producing and watching how people respond to my show have helped me understand how the arts are necessary to every student’s education. I learned that without artistic imagination, STEM students’ big-picture thinking skills can get stifled.

It only took writing a play for children for me to get it myself.![]()

***

Rob Roznowski is an award-winning actor, author, director, educator, and playwright. He is a Professor at Michigan State University where he serves as the Head of Acting & Directing in the Department of Theatre. He also coordinates the MFA program in acting.

This article is part of Art & Science Collide, a series examining the intersections between art and science.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.