At the most basic level, getting the people inside systems to actively acknowledge the impact other systems may have on their participants is a plus. I liken it to illustrator Saul Steinberg’s wonderful 1976 depiction of how New Yorkers view the world, with 9th Avenue in the foreground, the Hudson River in the middle ground and all else fading to the horizon behind. The more complex the system you are navigating in, the less bandwidth you have available to acknowledge the complexity of adjacent systems, even if doing so might make your job efficient or effective.

The increasingly frequent use of terms like education ecosystem, learning ecosystem, community or out-of-school time learning ecosystem is a positive first step. So is the progression beyond visuals from ones reminiscent of the New Yorker cartoon to ones in which the rich array of actors and institutions outside of school are put in a circle around more detailed description of the school system and simply labeled “community.” New visuals that more fully represent community are, not surprisingly, more likely to be developed by leaders in the community.

The increasingly frequent use of terms like education ecosystem, learning ecosystem, community or out-of-school time learning ecosystem is a positive first step. So is the progression beyond visuals from ones reminiscent of the New Yorker cartoon to ones in which the rich array of actors and institutions outside of school are put in a circle around more detailed description of the school system and simply labeled “community.” New visuals that more fully represent community are, not surprisingly, more likely to be developed by leaders in the community.

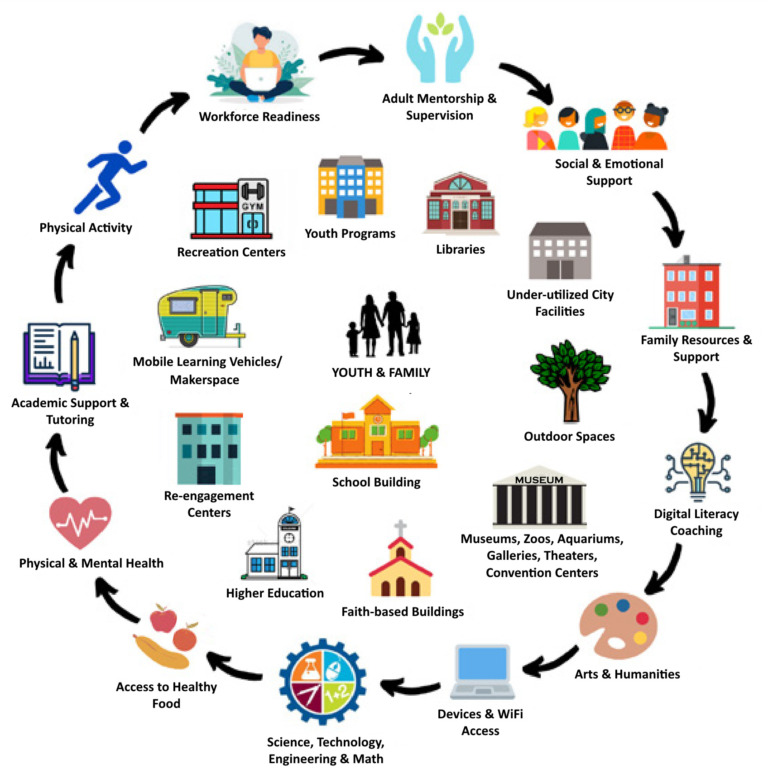

For example, the National League of Cities Community Learning Hubs Graphic, (which I previously shared in Why does public education require public schools?) puts the singular relationship between child/family and school in the center (since children only attend one school at a time). It then replaces the generic community ring with colorful icons depicting the array of community institutions that support place-based learning and development. And it goes a step further by introducing a third wheel of icons that help us visualize all of the kinds of learning and development supports and opportunities young people need beyond academic instruction. Even for those of us who talk about anytime, anywhere learning, this visual reminds us of the constant need to not reduce children’s and communities’ assets and needs solely through the academic lens.

Courtesy of National League of Cities

This model puts the singular relationship between child/family and school in the center.

The danger of doing this comes through in a recent Youth Today article entitled Post COVID summer programs didn’t boost kids academically but may have helped anyway. The title alone privileges academic recovery over the more basic, and in some cases more pressing, needs for reconnection, self-regulation and resilience-strengthening through interest-driven learning opportunities. The researchers quoted in the article acknowledge the benefits of gains in social-emotional skills and mindsets, remind us that summer programs are just a part of the solution and emphasize the importance of blending academics with hands-on learning and social skill building — as we saw many districts opt to do with their ESSER funded summer programs.

But the disappointment in the lack of academic progress is what comes through the loudest. The gains in math, though significant, were less than expected. And even though states receiving ESSER funding were almost twice as likely to include social-emotional elements (78%) than specific academics (41%), the disappointment that summer programs, while staving off learning loss, didn’t achieve heroic gains, led one researcher to go on the record with her intent to study summer school programs more closely next summer to investigate if the benefits justify the costs. And it led another to call for more attention to program fidelity — offering full-day programming with at least two hours of academics five days a week for at least five weeks.

The school system turned to another system — out-of-school time, or OST — to solve a problem: learning loss. But it only looked at a part of the broader community ecosystem. And it only focused on asking OST to do a modified version of what’s done during the school year. Looking at the full OST learning ecosystem could reveal other less costly and more sustainable options.

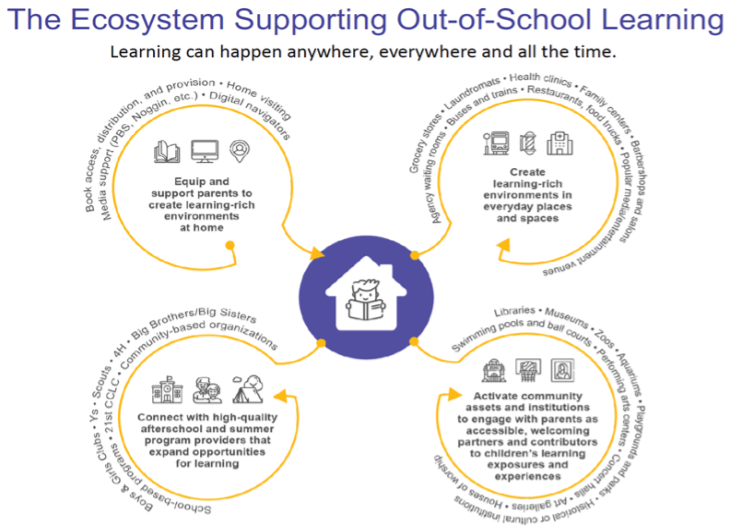

A recent graphic from the Campaign for Grade Level Reading’s Everyday Places and Spaces Initiative highlights the importance of empowering parents and community businesses to support learning. Moving clockwise, it starts with parents, moves to everyday places that are a part of families’ daily lives (like laundromats, barbers and grocery stores), then to the cultural and recreational places parents know about but don’t always have access to because of cost, transportation or comfort level. The graphic completes the circle with the structured community programs parents rely on for both childcare and interest-driven learning.

Courtesy of Campaign for Grade Level Reading Everyday Places and Spaces Initiative

Draft provided for discussion purposes.

As background, the Campaign for Grade Level Reading was created to address the impact of inequity on learners. Its mission is to “disrupt the generational cycle of poverty by improving prospects for early school success for children growing up in economically challenged, fragile and otherwise marginalized families.” Focusing on early school success, the campaign provides backbone support to a network of local and regional coalitions in more than 350 communities in almost every state powered by over 5,200 local organizations and supported by more than 100 national partners.

I like this graphic because it shows how, with coaching and coordination support, each type of learning setting (families, everyday places, cultural and recreational institutions, child care and afterschool programs) can strengthen their supports for learners, families and family learning.

The more I look at the graphic, however, the more I wonder where schools fit in? Are they a fifth circle? Are they a part of the invisible coalition that is building demand and orchestrating supports? Or are they, and must they be, their own learning ecosystem?

I’m not prepared to be satisfied with in-school and out-of-school learning ecosystem models. Graphics like those just shared help the school systems “see” the smaller more varied OST community learning systems. But if we are really following the lead of biologists, we will have to change how we see the ecosystem itself. I’ll end with a quote from colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh School of Education:

“It is no longer a collection of participants and learning places with separate essences that need to be connected for individual children. Instead, the learning ecosystem emerges as a constellation of intertwined and entangled elements, where learning happens through dynamic relational processes among the people, places, and stuff we find across/within/between school and out-of-school places.

By taking a deeper look and exploring the dynamic processes of learning ecosystems, we may be better able to manage systems that offer more equitable lifelong and lifewide learning opportunities.”

***

Karen Pittman is a partner at KP Catalysts and the founder and former CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment.