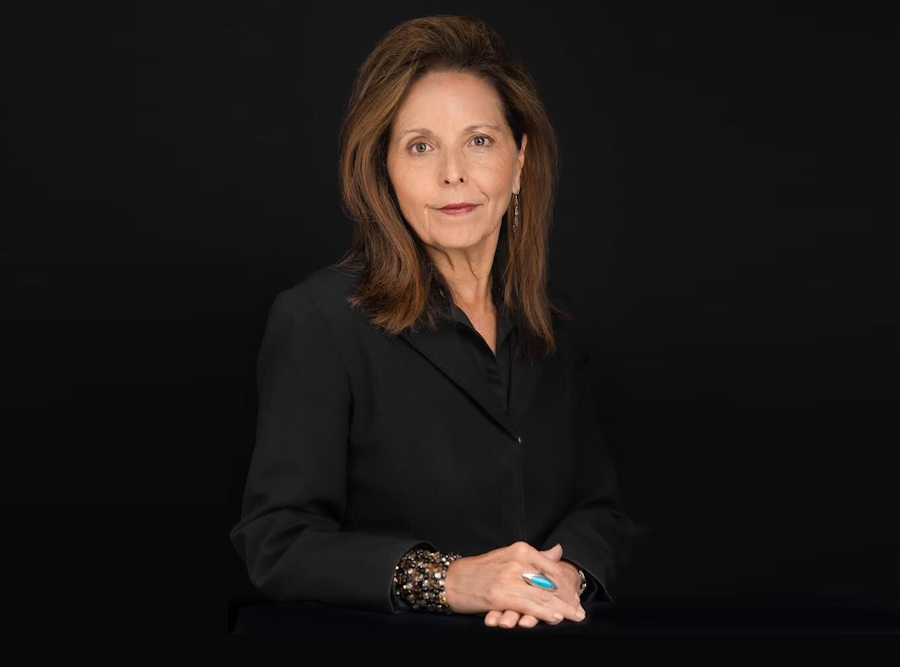

After transferring juvenile detention and rehabilitation from the state’s hands to that of California’s counties, Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed Katherine Lucero, a former San Jose judge, as the first director of the new Office of Youth and Community Restoration in 2021.

Lucero comes to that entity, which is part of the California Health and Human Services Agency, with her own backstory: She’d grown up with an alcoholic father — he got sober when she was 15 — in a home with dysfunctions like those she saw during her 20 years on the Santa Clara County Superior Court. There, she supervised the Juvenile Justice Court, presided over the Juvenile Court Division and launched therapy-based treatment courts for substance-abusing parents and traumatized teens.

Shortly before California’s last youth prison closed on June 30, reporter Brian Rinker interviewed Lucero about counties’ readiness to assume their new responsibilities and about her new role at that 30-employee office. Its divisions are charged with, among other tasks, delivering data-based research and health policy proposals; setting up an ombuds program to investigate complaints and have investigators meet with youth in juvenile facilities; engaging the public, including justice-involved families, and supporting the rights of youth who wind up in county detention facilities; and creating more equity regarding the race, region, economic status and other markers of people in the juvenile justice system.

What follows is an abridged version of that conversation.

Now that youth convicted of serious offenses are being sentenced to county-run secure youth treatment facilities near their homes, what authority does the Office of Youth and Community Restoration have over these new programs?

We’re not a compliance or regulatory body. We are solely focused on juvenile justice. Our interest is in creating as robust a continuum of care as possible for youth outside of incarceration. We are charged with everything from diversion and prevention to post-carceral to re-entry. It’s really the whole spectrum. We will also be running grant programs for the probation.

Other than that, our office has no actual authority over the facilities. Our ombuds officer can go in with 48 hours’ notice and she can ask to interview the youth.

If your office is not a regulatory or oversight agency, how do you get juvenile detention and probation departments to follow your leadership?

With the closure of a statewide youth carceral system, we’re on the brink of getting to do this really difficult work of shifting narratives, of looking at our youth as the children and youth that they are and not as criminals who need to be punished and stigmatized for all time. There are no kids to be thrown away. There are only kids to be cared for and reared. I think that counties are stepping into an era where they will be raising kids in a different way.

Our office will play an important role in mining data and creating dashboards. For example, how are youth doing educationally? Are these schools meeting the expected standards? On the behavioral health side, are the youth getting trauma-informed, individualized interventions? And, then … how is family engagement going?

That is how you begin to unpack what is needed for youth to leave feeling healed, welcome and competent for their next phase.

Still, how do 58 counties and 58 different probation departments collaborate and get on board with this continuum of care type of thinking?

One of my strengths from my work in Santa Clara County was bringing critical partners together: Behavioral health educators, social workers, probation, district attorneys and public defenders.

As a judge, I had that sort of a model court for years. The work of juvenile justice transformation does require all the partners at the table.

I aim to transfer that skill set to the counties and to the state. You have to remember, there are also a lot of state partners. We’re within the California Health and Human Services agency, but there’s also the Department of Education, the Department of Social Services and the Department of Rehabilitation.

We need to bring all the youth and child-serving entities together to collaborate to bring resources and best practices to the counties. That is how we’re going to be a leader. We’re really the only statewide leader now for juvenile justice transformation.

Advocates tell me the fallout of LA’s juvenile facilities, including the secure youth treatment facilities, are emblematic of other problems that are going on in juvenile facilities across the state. What have you seen?

I have visited all 36 secure youth treatment facilities. I’ve talked to their teams. I’ve seen youth in them. L.A. is extraordinary for its complexities and the issues that have been raised.

I’m not saying that all other 35 facilities are the gold standard. There’s a lot of room for improvement. I want our youth in secure youth treatment facilities for the least possible amount of time. I really want to look at that continuum of care.

And I want to follow brain science and research. What the data tell us is that, after a certain amount of time in custody, our criminogenic features are actually increased. So, I want to look at the science. I want to match science research and data with the leadership around how our youth are stepped down into the community, from the most restrictive site to a less restrictive site And that’s really the goal of my office.

You’ve called the state’s closing of its youth prisons a “momentous day.” Are counties ready to take over from the state?

What I have seen across the state is a level of desire to be ready.

This is a big shift. There has been a lot of preparation and we’re going to be seeing a lot of gaps filling and regional resource development for probably the next couple of years.

Some advocates say the transition is off to a rocky start. Are you satisfied with how counties are handling youth in these secure youth treatment facilities?

What I can tell you is that there’s a lot of room for improvement. Raising kids, in any circumstance, requires us to be and bring our best selves. And right now we have youth returning to counties to spend possibly multiple years in carceral settings that were not built for long-term detentions.

I think people are doing the best they can with what they have. But, there’s far more that needs to be done.

***

Brian Rinker is a Pennsylvania-based journalist who covers public health, child welfare, digital health, startups and venture capital. He reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 California Health Equity Fellowship.