Two-year-old Adam Bechtle’s favorite toy is a plastic dinosaur about the size of his head. It roars when he presses a button, and his current obsession is “scaring” his father, Jeff Bechtle, and social worker Christina Turner. They pretend to recoil in fear and Adam cackles in amusement.

“That gut laugh that little children get, that then makes you laugh,” was how Turner described the interaction with a grin.

But as recently as a few months ago, Adam rarely spoke or smiled.

“He just kind of had that flat affect,” Turner said, panning a hand over her expressionless face. “He just kind of sucked his thumb and just followed the mom around that tiny apartment and there was no playing to speak of. Very sad. It broke my heart.”

Adam’s mom was the reason that Healthy Families Kansas, the organization Turner works for, originally got involved in the family’s life. She and Jeff were dating when she found out she was pregnant with a previous partner’s child. Adam’s mom, addicted to drugs when she got pregnant, asked if Jeff would serve as the de-facto father. He agreed and was listed on Adam’s birth certificate as the father.

Because Adam was born addicted to drugs, Jeff said, the Kansas Department for Child and Families investigated the family while Adam went through withdrawal in the hospital. Instead of taking infant Adam into state custody, however, DCF decided to refer the family to Healthy Families Kansas, a program of Kansas Children’s Service League. If Jeff and Adam’s mom could create a safer living environment for their child, with the help of Healthy Families’ social workers, they could keep Adam. If they couldn’t improve their situation, then Adam would be taken into state custody for his own safety.

Courtesy of Jeff Bechtle

Jeff and Adam Bechtle

Social workers from Healthy Families, including Christina Turner, started visiting the family in their small apartment weekly. They brought Adam diapers and a toddler bed when he outgrew his crib and even helped with utility payments. They worked one-on-one with Adam to improve his fine motor skills and offered speech therapy. They also started early childhood special education interventions when Adam presented some signs of delayed development.

Adam was improving, the social workers say, as was Jeff in learning how to be a father for the first time. But they say Adam’s mother was still using drugs while Jeff was at work, which often led her to neglect Adam.

During one home visit last summer, Turner said Adam’s mom was high and began to yell at both Jeff and their toddler. She threw something on the floor near Adam and it came clear to both Jeff and the social workers that this violent situation was escalating.

“I looked at [Turner] and I was like, ‘Can you help me please?’” Jeff recalled.

“And I looked at Jeff and I said, ‘Do you want me to call 911?’ And he said yes,” Turner said.

From there, Adam’s mother was arrested and removed from the home, and began receiving treatment for drug addiction. Meanwhile, with Healthy Families’ continued support Jeff, 55, continued to care for Adam and receive help from Healthy Families.

Turner kept visiting with more resources from Healthy Families, especially parenting skills for now-single-father Jeff, and says the change in Adam from that time is remarkable.

“He’s just your normal kid,” Jeff said proudly. “He likes to play with his toys and watch cartoons, and he’s really independent and he tries to do everything himself.”

“I tell [Jeff] all the time what an awesome father he is and how lucky Adam is to have him take care of him and love him,” Turner said gazing at Jeff, equally proudly.

These Healthy Families Kansas services were funded by grants and reimbursement dollars under a 2018 federal law, the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA). The law’s aim is to keep families together, whenever possible. To that end, the law provides federal funding to locally-administered programs that provide counseling, education or other services to families to prevent child neglect or abuse and allow children to remain safely with their families. It also changes some guidelines about how long a child can stay in a foster home or group home.

“The goal of the Family First dollars is that instead of children being removed from the home and putting them into foster care, we want to provide these services to keep them at home,” said Kelly Hayes, director of Healthy Families Kansas.

Christina Turner says that without Family First, and the funding that goes with it, Adam may have been removed from his home after birth and placed in foster care.

Separating a child from their parents for even a brief period can be traumatizing, and children who are removed sometimes face mistreatment or abuse by foster parents. Under Family First, state child welfare agencies are given specific funding for programs that target the root causes of a family’s issues, such as substance abuse or a lack of parenting skills, rather than just taking the child away.

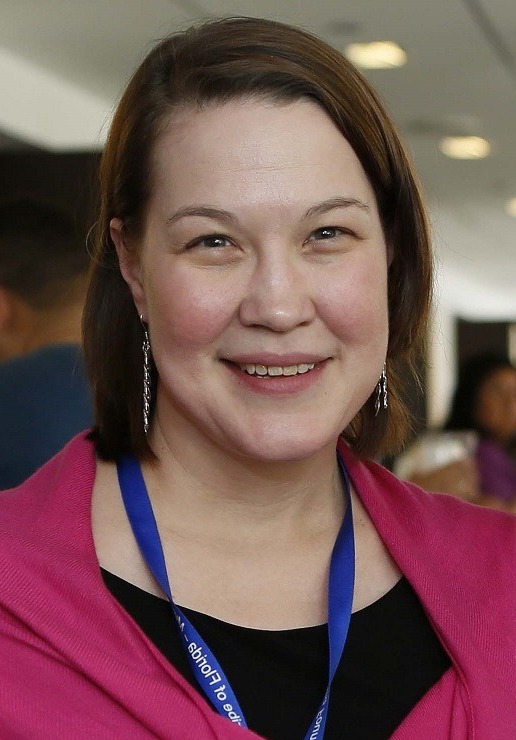

Courtesy of Clare Anderson

Clare Anderson, senior policy fellow at Chapin Hall

“Too often, families are reported to child protective services when they have unmet needs, which are better addressed through prevention services and other supports provided upstream of child welfare in order to reduce the likelihood of foster care entry,” said Clare Anderson, senior policy fellow at Chapin Hall, a research nonprofit at the University of Chicago.

Kansas was one of the first states to implement Family First, and Kansas Children’s Service League won one of the first grants in the state. According to Kansas’s Department of Children and Families, DCF referred 3,649 families to Healthy Families Kansas for preventative services instead of immediate removal since its inception in October 2019; as of December 2022, 88% of those families still remained together at home 12 months out, without evidence of abuse or neglect. Five percent of children in those families were removed from their homes after DCF found evidence they had been abused or neglected.

But Kansas is an outlier.

Five years after the passage of Family First, implementation nationwide is progressing slowly but steadily, with $194 million distributed and thousands of families kept together, according to state by state data.

Experts say there’s more to be done, with millions of federal dollars still unclaimed and inequalities that remain unaddressed — especially in how the program affects American Indian and Alaska Native tribes.

From passage to implementation

Congress passing Family First was the first step on a long road to parents like Jeff Bechtle getting help. Under the law, each jurisdiction (a state, territory or tribe) must first develop and submit a five-year plan for how they will implement Family First to the federal government for approval. They select which practices, like in-home family visits or cognitive behavioral therapy, will be offered.

For example, California has submitted its state-wide plan already, though it remains unapproved. A spokesperson from the California Department of Social Services told Youth Today that so far 50 counties and two tribes have opted into future Family First programs and are working on their own local-level plans. Those aren’t due to the state until July 31, 2023.

Nationwide, 50 of 64 total jurisdictions have five-year plans that are approved or pending final federal approval, according to publicly available government data as of January 2023.

After a jurisdiction has an approved plan, however, it must build the computer systems and hire the staff needed to collect and disperse funds and file quarterly reports. Only then may jurisdictions apply for grant funding for Family First services. However, some of that funding can be used to retroactively pay for services already offered. For example, Pennsylvania is still waiting for its submitted plan to be approved, but is already implementing Family First prevention services with state and local money, with the expectation that its plan will be approved and then get federal reimbursement for services provided.

According to federal data, only 21 jurisdictions have actually been issued grant awards as of April.

Tribal impact

Tribes face unique challenges in implementing Family First, especially in making sure that their cultural practices aren’t disregarded.

“When we look back at American Indian and Alaskan Native cultures and societies in this country, before colonization [and] Western contact, we had robust ways of caring for kids and families,” said Sarah Kastelic, executive director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association and an enrolled member of the Native Village of Ouzinkie. “Children were not viewed as the responsibility of just their biological parents, but children were viewed as sacred. They’re viewed as gifts from the creator. And part of the natural fabric of native communities of tribal culture was to care for children collectively.”

Courtesy of Sarah Kastelic

Sarah Kastelic, executive director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association

Family First does give tribes more flexibility than states in which prevention services they choose to implement (for example, parenting classes specifically about how to raise an indigenous child) but still requires tribes go through a complex approval process. And nearly all tribes are limited to picking from prevention services that have been extensively researched in academia — a requirement that effectively excludes some cultural practices. As of April, only three out of 574 federally recognized tribes had approved Family First five-year plans.

One is the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, which has about 70 children in its own child protective custody at any given time, out of about 16,000 total people in the tribe.

“The paradigm shift that we wanted was [from], ‘Oh no, they’re coming to take my children,’ to ‘Thank goodness, there’s our local agency, they’re going to help me keep my children,’” said Vickie Bradley, secretary of public health and human services for the tribe.

All tribes should be able to have the flexibility to create their own programs, said tribe Secretary of Public Health and Human Services Vickie Bradley, especially since many widely-used programs have not been tested on indigenous populations.

“We are seeing generations that have been intersected with the child welfare system,” Bradley said. “We’ve chosen to be slow and intentional about the process to ensure their families are receiving exceptional, sustainable services which meet their needs.”

Moving forward

Many experts told Youth Today that five years after the law’s passage is too early to accurately evaluate results of implementation, because some states are still in the planning phases and because the coronavirus pandemic halted many services, especially those offered in-home.

Courtesy of Vickie Bradley

Vickie Bradley, secretary of public health and human services for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

But still, experts say the passage of Family First marked a watershed moment in changing how the country handles child safety overall.

“Family First marks an important moment as it elevates prevention and states are implementing important programs and creating new or alternative community pathways for meeting the needs of families proactively,” Anderson, of Chapin Hall, said. And implementation is moving ahead. In just March 2023, the Department of Health and Human Services issued 20 more grants across more than a dozen states.

That includes Kansas, where Jeff and Adam love watching Peppa Pig and Paw Patrol together. With more funding, social workers can provide even more services to families like theirs, keeping children at home. Jeff says those services are not only good for Adam, but himself too.

“It’s just me and Adam. When [Turner] comes over, it’s like I get to visit with her. I mean, I know she’s here for business reasons, but I kind of feel like we’re friends too.”

***

Nora Neus is a New York City-based freelance journalist and author whose reporting has appeared in publications including CNN, VICE News, POLITICO Magazine, Teen Vogue and the Washington Post.