After Keelan McCormick was suspended five times from kindergarten in one month, his mother decided she had enough.

Keelan was reading graphic novels at age 4 and had an analytical mind gravitating toward STEM. He liked coding on the Mac set up in his bedroom.

But in his New Hampshire public school kindergarten classroom, students were learning how to put words together while Keelan got bored and got up to move around the classroom, pacing to help calm him down, his mother Kendra Rozett McCormick said. His behavior deteriorated, and sometimes he kicked or slapped staff. That year, he was diagnosed with ADHD and anxiety.

School staff often responded by locking Keelan in a padded room with a two-way mirror when he got physical, Rozett McCormick said. That only made things worse since his biggest fear was being alone.

“I felt like I needed to find a better place for him,” Rozett McCormick said. “I felt like the public school really was trying to make kids fit into this neurotypical box, and if they didn’t fit into that box, they sort of punished them.”

So in November 2021 Rozett McCormick enrolled her son at a Prenda microschool with about 15 students. She has joined the ranks of parents turning to microschools — schools known for their tiny class sizes and flexible learning models — which for children on the autism spectrum or diagnosed with ADHD or anxiety can be a better fit than traditional public or private schools, some parents say.

Microschools occupy a space between homeschooling and private schooling but can get public funding, blurring the lines in the educational landscape.

Microschools can be run by a company with a national franchising model — like Keelan’s school at Prenda — or be as informal as homeschooling children gathering together in a parent’s home. Some burnt-out public school teachers eager to create change in the system have formed their own microschools.

Some microschools educate 10-15 students while others are bigger, according to University of South Carolina educational research professor Barnett Berry. Most charge tuition, according to a report by Vela Education Fund, which supports community-driven education startups nationally. Estimates for annual tuition for a 9-month school year range from $5,850 in recent months to about $11,000 during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to two studies. Other microschools operate as public schools and don’t charge tuition at all.

Students with disabilities are the ones with the most to gain from this flexible style of learning at microschools, said Travis Pillow, a senior writer at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, or CRPE, an education research organization based at Arizona State University.

But Pillow said these students also have the most to lose if microschools, many of which are not required to follow federal laws protecting students with disabilities, don’t provide enough resources to support them and let them fall behind. And, since many microschools can pick and choose who they admit, some students may be shut out from the start.

Regulations for microschools

There’s a wide range of rules for microschools depending on location and whether they are classified as private or public, Pillow said.

Many states allow microschools to operate as unaccredited private schools; those microschools aren’t typically regulated for seat time requirements, curriculum approval or educator and administrator licensing, said Don Soifer, chief executive officer at the National Microschooling Center, a nonprofit that’s a resource for microschools.

In other states, microschools follow the state’s homeschool requirements, Soifer said.

And in other places, microschools have formal arrangements with charter schools; these microschools follow the same requirements as to charter schools, like having curricula meet state academic content standards, Soifer said.

Courtesy of Shiren Rattigan

Shiren Rattigan, Colossal Academy

Pillow warned it’s hard to know if microschools are meeting academic standards.

“One issue is that microschools just break a lot of our assumptions around how school accountability would normally work because they are so small,” Pillow said. And since microschools are so small, “aggregate test scores aren’t going to tell you very much,” he said.

CRPE researchers say it’s unclear how many microschools exist across the country and how many students are currently enrolled. The advocacy group EdChoice estimated 1.1 million to 2.2 million children are enrolled full-time in microschooling. What’s certain is more states are pushing for school choice policies that could free up additional public money to be spent on private school tuition, like at a microschool.

As of last year, eight states had education savings account programs, or ESAs, that allow parents to receive public money to spend on their children’s education, according to EdChoice. Pillow said three more states are passing legislation this year to add ESAs for the first time while other states are expanding their existing programs.

What microschools offer

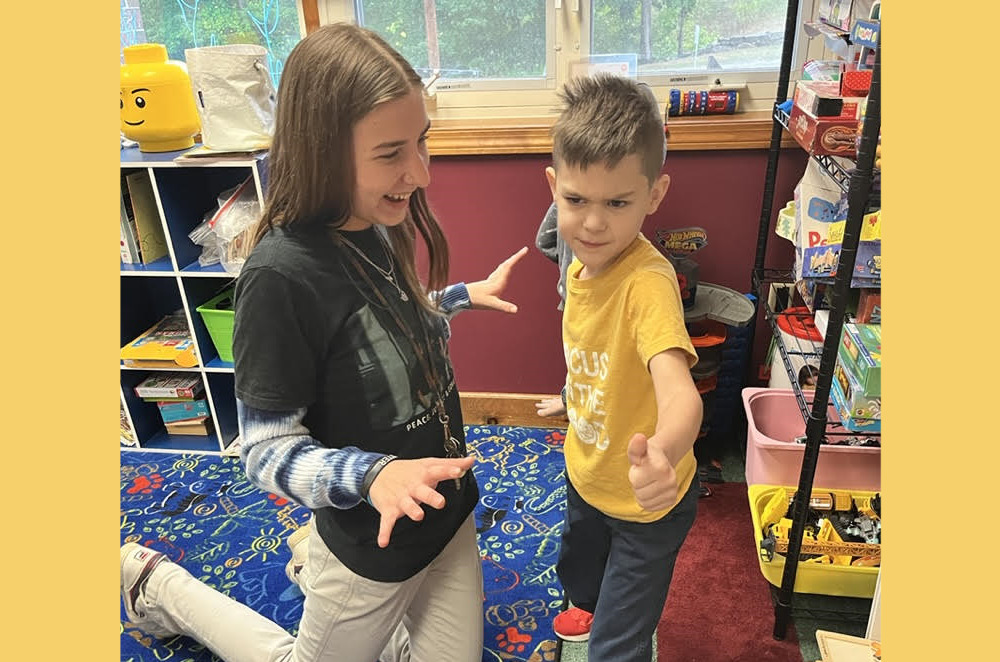

At Prenda, Keelan’s first-grade teacher doesn’t mind when it’s math time but he needs to let his wiggles out in the breakroom. Ten minutes later, when Keelan is ready to focus, he plops down on a futon or rocking chair, not the hard chair he was stuck sitting in before at his old public school.

Since his class has less than 10 students, Rozett McCormick and Keelan’s teacher, who is called a “guide,” are in constant communication, text messaging back-and-forth if Keelan is having a bad day or a good one.

When Keelan threw things and got physical early on, the school didn’t suspend him. Instead, the school asked Rozett McCormick to come in and help calm him down in the classroom, an invitation she said didn’t exist in the public schools.

Keelan, now 7, comes home happy and in a good mood,” Rozett McCormick said.

“At the same time, you can tell he’s mentally tired because he’s worked hard, so he’s looking to relax. To me, that’s a good sign. He doesn’t come home all fired up because he’s been bored all day,” she said.

Keelan’s parents don’t pay tuition because the school, through Prenda, an Arizona-based company, gets funding from the state of New Hampshire. The leader of Keelan’s 15-student school rents commercial space in a brick building off a walking trail. Within the 3,300-square-foot school, there’s a gym area, an arts and science room and a kitchen with a small cafeteria.

Other microschools offer non-traditional environments, like Colossal Academy in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where students surf in the ocean, do science lessons on the sand and skateboard on Fridays. Their school, in a space that was formerly a pottery studio, has a butterfly garden. The relaxed learning environment helps students, especially those on the autism spectrum, dyslexia and ADHD, succeed, said Shiren Rattigan, who runs the school for 10-to-14-year-olds with 27 students in-person and 17 online.

Courtesy of Shiren Rattigan

Students at Colossal Academy in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., surf on Fridays.

At Capitol Learning Academy, a 13-student microschool in Washington D.C., students who have disabilities don’t feel singled out since everyone learns at their own pace with online lessons, games and worksheets, said Alexandra Roosenburg, who runs the school. The school staff leaves out fidget toys and has a calm down corner and flexible seating options everyone can use. Roosenburg said she focuses on if children are developmentally ready to learn rather than if they’re on grade level.

Accessibility at microschools

Microschools in many ways embody the ideal of the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which requires public schools to serve the needs of students with disabilities, said Lauren Morando Rhim, executive director of Center for Learner Equity, a nonprofit advocating for students with disabilities in public education.

“You look at each child, you provide the services and support, and you deliver the education in a way that the child can access it, and that’s wonderful,” she said. “Where it becomes more complicated is when the child needs more services,” such as specialized instruction for dyslexia or speech or occupational therapies.

Microschools run as small charter schools or traditional public schools need to provide the accommodations identified on students’ individualized education plans and admit students without regard to disability, according to Morando Rhim. Individualized education programs, or IEPs, are designed to make sure students with disabilities get the specialized instruction and services they need as required under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

But microschools operating as private schools aren’t required to provide any accommodations nor accept all students, she said.

Courtesy of Alexandra Roosenburg

Alexandra Roosenburg, Capitol Learning Academy

“The microschool is most likely in a position to say, ‘Here are services we offer. If your child fits in, then we’d love to have your child. But if your child doesn’t fit in, then your child can’t come,’” Morando Rhim said.

Even though she runs a private school, Rattigan of Colossal Academy said her goal is to provide what every student needs. She said if she needs to hire a reading specialist for additional support, for example, she does. Her school charges $14,500 a year in tuition, although Rattigan said most parents end up paying less as she fundraises and some children receive state-funded vouchers.

Roosenburg, of Capitol Learning Academy, said her school’s model “naturally” caters to students with dyslexia, ADHD and autism. But students need to be highly independent to succeed with the school’s self-guided lessons, she said.

“We don’t want the children to be frustrated either,” she said. “We want to find the right fit for both sides of the equation.”

‘A real tension’

All students should have access to microschools and their benefits, said CRPE principal Ashley Jochim, who co-authored a 2022 study on microschools’ rise during the pandemic. Yet at the same time, these little schools with limited resources and staff can’t possibly serve every purpose and be everything to everyone, she said.

“There’s a real tension around this point of accessibility,” Jochim said. “We don’t want a situation where all of this entrepreneurship and an opportunity that comes with this new form of schooling (is) soured as a result of maybe a few bad actors who exclude students when maybe they shouldn’t have.”

Some public school advocates fear the popularity of school choice could also financially devastate public schools.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a universal school voucher bill into law in late March that frees up more public money — estimates range from $646 million to $4 billion — to be spent on private school tuition and for homeschooling for all students, not just low-income students or students with disabilities. He called it “the largest expansion of education choice not only in the history of this state but in the history of these United States.”

In some states, there has also been pushback, like in West Virginia, where three parents of children with special needs sued in 2022 over a 2021 law for the state education savings account program. The lawsuit said the state’s new program would be “siphoning millions of dollars away from public education” to private schools which are unwilling or unable to serve students with disabilities. The litigation, which went all the way up to the state Supreme Court last year, delayed the voucher program for months but the program has been reinstated.

But for other parents and students, microschools are simply the option that works best for them.

High school freshman Alex Nestmann switched to a microschool this school year after previously attending a large public middle school. He attends ASU Prep, part of a public charter school network operated by Arizona State University.

“I don’t like big groups of people,” Alex said so he feels less stressed in his cohort of about 15 students where he takes an in-person elective on cinematography alongside his online coursework.

“It has definitely turned into the opportunity we thought that it might be for Alex,” said his mother, Annique Petit. “To have a 15-year-old boy loving school, like ‘Amen.’”

***

Gabrielle Russon is an Orlando-based journalist who covers education and business.