When he woke up shivering and handcuffed to a hospital bed two years ago, John was shocked by what police told him he’d done while high on a cocktail of cocaine, marijuana, acid and whiskey:

Seventeen years old at the time, he darted out of the Columbus, Ohio, apartment he shared with his mom and argued with a neighbor who’d asked him to turn down his music. When that neighbor slammed his apartment door on that belligerent teen and it banged into John’s face, the teen ran back inside his home to grab a baseball bat. Minutes after he used it to smash the windows of that neighbor’s car, the vandal shoved a police officer who’d been summoned to the scene.

“I was so ashamed and so shocked. Everyone in the hospital avoided eye contact with me and acted like I was going to bite them,” said John, adding that he’d been triggered on that night in January 2020 by his parents’ pending divorce. Because his expunged juvenile record helps him avoid the societal barriers often confronting those with criminal histories, he asked Youth Today to identify him by only his first name.

Charged with possession and use of marijuana and cocaine, destruction of property, disorderly conduct and assaulting a police officer, he stood before a juvenile court judge imagining that he’d be sentenced to years of incarceration. (Police found no evidence of acid on the scene, so he wasn’t charged with abusing it.) Instead, the judge sent him to drug court, a 15-month program providing medical treatment for substance abuse; psychological counseling; mediation and relationship-building services for substance abusers’ families; and assistance seeking education and employment.

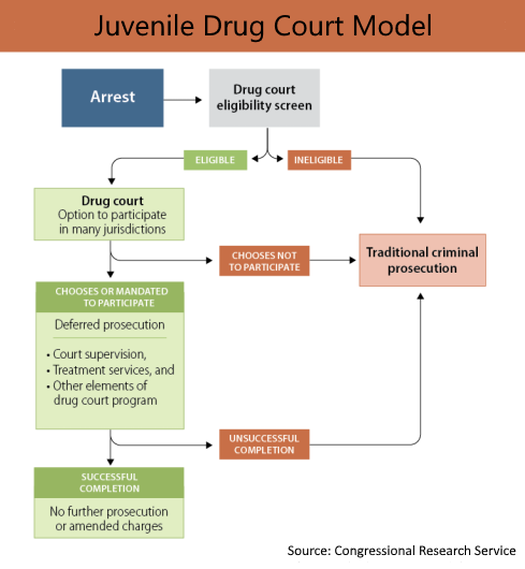

Those like John, who successfully complete the program, see their criminal charges dropped in drug courts, a treatment-based model of diverting individuals from lockdown. About 1,750 juvenile drug courts are included among the nation’s tally of more than 3,500 drug courts, a system with its supporters and its critics.

In 2019’s “How Drug Courts Fall Short,” the Social Science Research Council concluded that those niche courts “ … can increase the supervision of individuals and expose them to more severe penalties than they would otherwise have received, thus sometimes becoming an adjunct rather than an alternative to incarceration.”

In 2019’s “How Drug Courts Fall Short,” the Social Science Research Council concluded that those niche courts “ … can increase the supervision of individuals and expose them to more severe penalties than they would otherwise have received, thus sometimes becoming an adjunct rather than an alternative to incarceration.”

Yet, the National Association of Drug Court Professionals, which, with the federal government, maintains an interactive map of juvenile and adult drug courts, has called those specialized courts the “single most successful intervention … for leading people living with substance abuse and mental health disorders out of the justice system.” And while The American Civil Liberties Union contends that the data are too limited to be reliable, it also argues that there’s anecdotal evidence of drug courts’ successes.

Yet, within two years after graduating from drug courts, 66% of those alumni were rearrested, which compared to 81% of non-drug court participants, according to an Evidence-Based Professionals’ Society meta-analysis, released in 2017. Citing the varying and sometimes conflicting results of several previous studies, that analysis also found that drug courts reduced recidivism, on average, by 7.5%; and that the re-arrest rate was 45% for drug court participants, compared to 55% for non-drug court participants.

Judge’s frustration yielded Ohio court

Courtesy of Judge Peeler

Judge Robert W. Peeler

In Ohio, Warren County Court of Common Pleas Judge Robert Peeler, a former prosecutor who created one of the state’s earliest drug courts, said they work and are a good idea.

“I realized that this is not a question of, ‘Did you do it or not, but can you stop?’ I know we can’t incarcerate our way out of the problem because these are not hardened criminals,” Peeler said, of the mainly low-level, non-violent offenders accepted into drug courts. “They have a disease.”

In 2009, Peeler’s frustration over having so many substance-abusing offenders on his docket peaked. From that point, it took him six years to launch Warren County Drug Court’s 15-month-long program. To prevent relapses of those with opioid addictions, Peeler also ordered what then were 120 incarcerated offenders to get a $1,000-a-month shot of naltrexone to treat their opioid and/or alcohol addiction.

Critics questioned the fiscal prudence of that. But Peeler successfully lobbied for an $832,000 inaugural state grant to pay for the treatment, lasting from six months to a year.

“They are human beings,” said Peeler, lauding such funding. “They deserve respect because they are in recovery … They have people who care about them, and it builds their self-esteem.”

Also in Ohio, the juvenile drug court that Butler County Court of Common Pleas Juvenile Division Judge Erik Niehaus started resulted from his private research.

Courtesy of Judge Niehaus

Judge Erik Niehaus

“Drug court sessions are like roundtable conferences. Participants interact with court personnel, counselors, probation officers, case managers and attorneys,” said Niehaus, who hosts bimonthly sessions in his chambers where parents and guardians of drug court participants.

That collaboration, he said, is to help ensure that justice-involved youths’ relatives are supporting and monitoring the teenagers’ progress. Among other requirements, participants have to be in school or employed. They are randomly drug-tested and monitored by school guidance counselors for how well they cope with their academics and other aspects of school.

“I have cried many times. Sometimes they are happy tears,” Niehaus said.

Drug court is cheaper than prison

Drug courts for juveniles got their start in the mid-1990s, trailing adult drug courts, which were launched in 1989 in Dade County, Florida.

In 2021, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention awarded $7.86 million to provide resources to state, local and Native American tribal governments to create and enhance juvenile drug treatment court programs. The federal agency allocated $4 million in 2015 and $3 million in 2016, respectively, for such training and technical assistance.

Courtesy of Monique Thibodeau

Monique Thibodeau

Each criminally charged drug-abusing participant costs drug courts cost $2,500 to $4,000 annually, concluded Stanford University researchers, also estimating that incarceration costs $20,000 to $50,000.

Monique Thibodeau is among those landing in Peeler’s court who’d started using illegal drugs as a teen. She smoked marijuana, then snorted cocaine, then, in 2011, while she was a college freshman, added heroin to the mix. It made her feel like she was wrapped in “a big warm hug.”

It also, said the now 38-year-old, “ruined my life … I couldn’t do anything but get high.”

After five years of trying, she graduated drug court in 2016. She was fortunate that Peeler gave her second chances when she lapsed back into drug use.

The program “changed my life. I wouldn’t have been able to stop on my own,” said Thibodeau, whose relapsing also prolonged her studies at the University of Cincinnati where, after a decade, she graduated.

Today she has a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and monitors content for works at a social media for TikTok.

With her drug abuse also starting when she was a teenager, Heather Bryd, now 32, also cycled through Peeler’s court.

Byrd, a single mother of two, graduated in April 2020. During the two years it took her to complete the program, the court helped her secure housing, transportation, medicine and child care, she said. It also bestowed upon her respect critical to finishing the program.

Courtesy of Heather Byrd

Heather Byrd

“The judge spoke to me like a real person. I was helped and supported. It changed me. It wasn’t always easy but, if I hadn’t tried it, I would have lost my life,” said Byrd, who’d abused morphine, fentanyl, black tar, speed and, in exchange for sex, heroin.

She lost count of the times she overdosed during a period when she also got evicted and had child protective service workers place one of her kids in her sister’s home and one in her father’s. She lost her furniture, appliances, cookery, clothes, romantic relationships and the last in a series of jobs she’d held in restaurants and retail stores.

She’d showed up in drug court after being criminally charged for stealing cash from and fraudulently using a credit card belonging to the man she’s slated to wed in June 2023 wedding, said Byrd, a hair stylist — whose second job has her stocking shelves at a retail store and whose third job has her packing boxes for a shipper serving commercial clients.

Falling hard but getting up again

High on methamphetamine, Franklin, Ohio, machine operator Jason Lawson collapsed on a street corner, breathing heavily, fearing he was dying of a heart attack two years ago. But it was the meth, battering his body.

Courtesy of Jason Lawson

Jason Lawson as a teen

“That became my wake-up call,” said Lawson, whose sons Jamie, now 21, and Bradley, now 18, were placed in his sister-on-laws custody after that episode.

Now eight months into the drug court program that he started soon after that scare, Lawson, 42, said he started smoking marijuana when he was 13. Then, he dabbled in “everything you can think of, [always] looking for a new high.”

Before using meth, Lawson was addicted to crack cocaine. Still, he was what’s known as a functional addict, always keeping a job and managing, in some ways, to mask his addictions at work. Yet, Lawson added, going through drug court has made him more clear-headed and confident than ever as he turns his life around.

John, now 19, also credits that juvenile drug court and its judge with his turnaround, following the day, high on that cocktail of substances, he bashed his neighbor’s car windows.

Since graduating, he has not touched any illegal drugs, John says. Wine at a special event is the only alcohol he’s allowed himself.

“It saved me,” he said, of Peeler’s court. “It scared me straight.”

***

Sonia Chopra is a Cincinnati-based journalist who covers criminal justice policy and courts.