This story was originally published by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

To some in the audience, Jeremy White sounded like he was preaching.

“I was 19 years old when I got incarcerated. I was facing 120 years,” White, 42, said, his words deliberate, his cadence suited for a Sunday morning pulpit, his Tennessee drawl full on.

“ … [I began] remembering where I came from … ”

“That’s good, that’s good!” Vickie Woodard exclaimed.

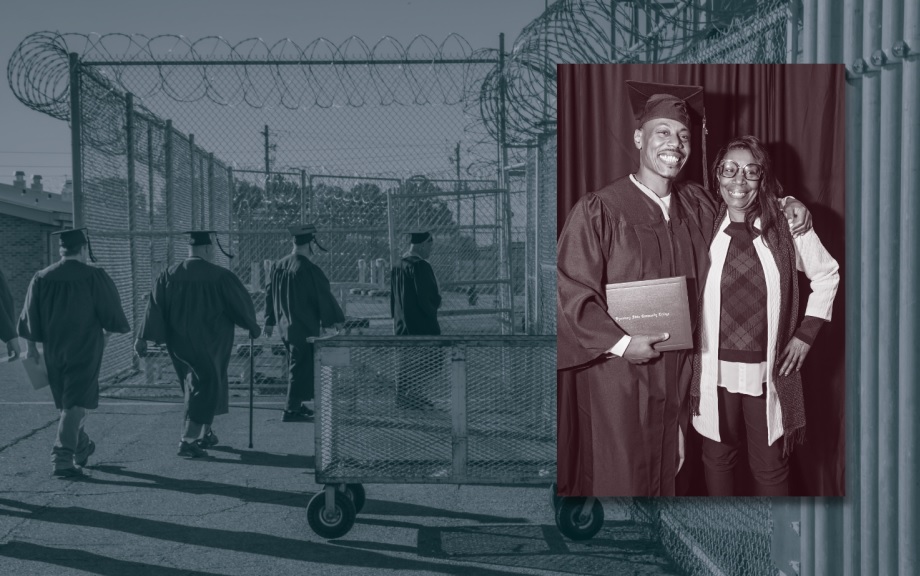

Woodard’s son, Almeer Nance, was among the 13 men in caps and gowns, seated on the front row of an assembly hall inside Northwest Correctional Complex. White, the Tennessee Higher Education in Prison Initiative transition coach who’d spent 22 years in prison, scanned the men’s faces. He testified and encouraged.

“We’re shifting the narrative of what it means to be incarcerated and formerly incarcerated,” he said. White is also an administrative assistant in the Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development’s year-old Office of Reentry. We must, he said, “shift the culture in prison and change the narrative, including outside these prison walls … Our moment is now.”

Convicted of robbery and attempted murder, White earned his associate degree from Nashville State Community College in 2022. He’d begun his studies while still incarcerated.

Along with housing and job training, education is deemed critical to thriving after leaving prison. It’s a path to economic sustainability, according to several analyses that link the ability to sustain oneself to whether or not justice-involved individuals resume the criminal activity that landed them behind bars.

Offering a college education or, for that matter, high school completion in prison has fallen in and out of political favor over the years. In 2020, lawmakers lifted a 26-year ban against extending federal Pell Grant eligibility to inmates pursuing college degrees. Congress proposed and former President Bill Clinton signed that restriction in 1994 — when 23,000 of the nation’s 4 million Pell grantees were incarcerated — during that tough-on-crime era.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Education, in a 370-page guidance, spelled out new regulations for how colleges can enroll those among the nation’s 1.2 million convicted prisoners who, beginning in July 2023, may choose to apply for Pell Grants. (According to the latest count, an additional 734,000 individuals were detained in county and municipal jails, which usually are reserved for those awaiting trial.)

Despite the 1994 ban, several states, partnering with colleges and private organizations, had continued to offer educational programming to the incarcerated. And, in 2016, 67 colleges were participating in the Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative. Four years later, that tally had risen to 130 colleges in 42 states and the District of Columbia, according to a 2021 report from Vera Institute of Justice. It gives technical support to college programs inside prisons.

A 2019 report from the nonprofit Vera found that most prison college programs were funded through that 2016 experimental initiative, serving up to 12,000 incarcerated students annually. Additionally, the report found that 64% of prisoners were academically eligible to enroll in postsecondary educational programs. Lifting the ban against extending Pell Grant eligibility to the incarcerated would immediately result in 463,000 of them being eligible to apply.

From the grad day stage at Northwest Correctional, Dyersburg Community College President Scott Cook lauded schooling for the incarcerated.

“We know from the data, over and over again, that … prison education is where you change lives,” said Cook, whose campus runs Northwest’s program. Dyersburg, one of six Tennessee colleges with prison programs, was graduating its second cohort at the Tiptonville prison.

Nance was among them. “He’s the first one in our family to graduate,” Woodard said.

For many reasons, that’s significant, said Nance, 43, convicted at 16 for helping to rob a Knoxville Radio Shack and being an accomplice to Robert Manning’s murder of the store’s 21-year-old clerk.

“So many people, so many young Black men, like I did, grow up seeking a place to belong, to fit, overcompensating for what they don’t have. We wind up in so many wrong places,” said Nance, who’s now studying for his bachelor’s degree through Lane College’s prison program.

“Education,” he added, “empowers people to be comfortable with who we are. It’s self-actualizing.”

Nance’s daughter, Jameerial Johnson, 24, said she’s tracked how college studies have changed her father’s outlook.

“My dad would tell me, ‘I got all As’ or something like that,” she said. “He’s defeating odds that a lot of people out on the street, free, don’t even defeat. He’s showing that there is nothing that cannot be done.”

Memphian Tony Jamerson, 59, was another of those graduates. “I have loving parents,” he said. “They taught me the value of a good education. Drugs drove me down a whole other road.”

Confirming his testimony was his mother, Amy Brooks, 75, who’d driven up from Memphis. “Today is a wonderful day. I’ve always wanted him to excel. And he is doing that.”

***

Katti Gray is an editor for Youth Today and the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. She specializes in health and criminal justice news and coordinates national journalism conferences and fellowships for the Center on Media, Crime and Justice at John Jay College and the Association for Healthcare Journalists. She shares a Pulitzer Prize with a team from Newsday and has served as a committee juror and chairperson for the Pulitzer Prize committee.