West Charlotte High School had let out only minutes earlier when, hearing gunfire, school officials ordered an immediate lockdown and Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department officers swarmed the campus. That incident, the week before Christmas break 2021, was the ninth time a gun had been found at one of Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s most troubled public schools since the start of the school year.

West Charlotte, where 99% of students are Black and brown and 100% of them qualify for free school meals, is just one campus of the state’s second largest school system where kids are carrying guns. Officials found and confiscated 30 guns from students on school property during the 2021-22 school year, eclipsing the previous record of 22, set in 2018-19.

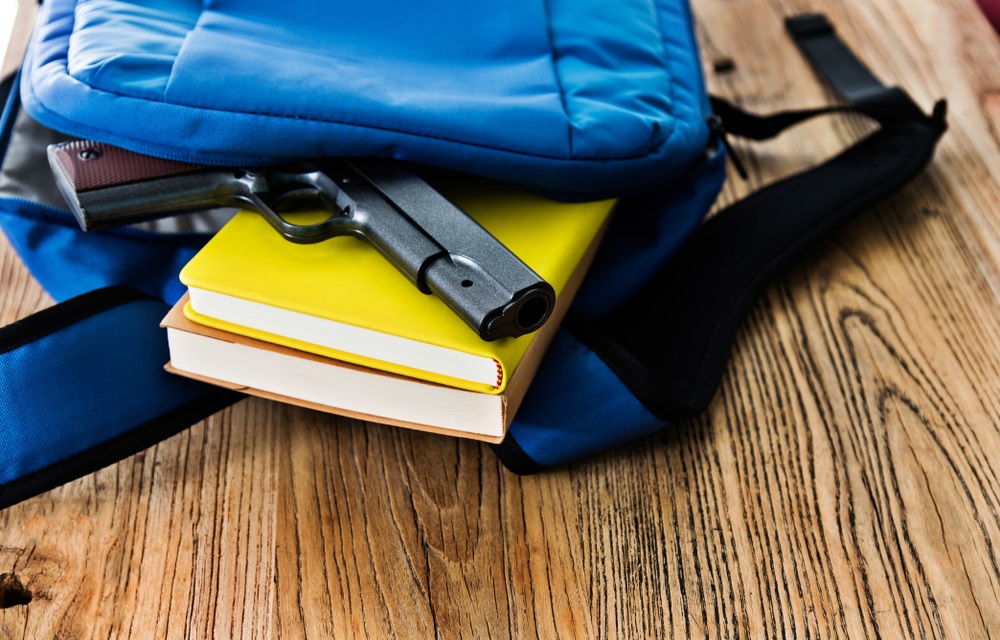

When three guns were found on two high school campuses in one day, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools Superintendent Earnest Winston made an impassioned plea to parents for help. “Please talk to your students about the consequences of bringing guns to school and about the consequences associated with gun violence,” said Winston, in a recorded video message. “Have the tough conversations about guns, check their backpacks before they depart for school. This … can help them continue their academic journeys, instead of entering the criminal justice system …”

“We have seen an increased number of firearms coming onto school campuses around the state,” said William Lassiter, deputy secretary for Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention for the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, explaining some reasons why. “During the pandemic, a lot of people went out and got permits for firearms for the first time in their lives. And a lot of those adults aren’t necessarily securing those guns very well.”

Indeed, elsewhere in the state, there have been more guns at schools. Just days after the fall 2021 semester began at New Hanover High School in Wilmington, a dispute between two students led to one injured by gunshot and the other charged with attempted murder. In Elizabeth City, an AK-47 semi-automatic weapon with a 30-round magazine was found on a school bus. And in rural Robeson County, an 8-year-old brought a gun to the elementary school playground to show it off.

Fearing attack, some carry weapons

In Winston-Salem, N.C., eight days into Tabor High School’s 2021-22 school year, dozens of students watched as 16-year-old sophomore William Chavis Renard Miller Jr. and a friend approached 16-year-old Maurice T. Evans in the hallway. As they drew nearer to each other, Evans pulled a gun from his backpack and opened fire, striking Miller in the stomach. Miller crumpled to the floor. During the ensuing panic and chaos, Evans fled the building and dumped the gun and backpack in a garbage bin. He was arrested six hours later, indicted for murder and held without bond at a juvenile detention center in Greensboro.

“Maurice felt he was going to get jumped by other students, so he brought the handgun,” one student told investigating officers, according to police reports.

“The data pretty clearly shows that when you ask children why they’re bringing guns to school or why they’re carrying guns in general, they say it’s because they want to protect themselves or to deter others from picking on them,” said Kelly Drane, research director for the Giffords Law Center. “Children that have been the victim of violence or bullying and other kinds of conflict are more likely to carry a gun and children who witness that kind of violence, even if they’re not directly impacted, might feel like they need to carry a firearm.”

Interventions to stop that should go beyond what happens on school property and encompass ways to make the child’s community safer, she added: “Even if their school is relatively safe but their walk to school bus or through their neighborhood is dangerous, they’re carrying a gun to protect themselves from violence outside of the school.”

Lassiter said the North Carolina Department of Public Safety is conducting ongoing surveys among students to determine what’s driving the fear. “We want to understand. What are they trying to protect themselves from?” Lassiter said. “How do we deal with the root cause of why kids feel unsafe? The gun is just a symptom of that feeling.”

A 2017 study published in Pediatrics found that teens who skipped school because they feared for their safety were three times more likely to carry a weapon than kids not experiencing bullying. Meanwhile, kids who had fights at school were more than five times likelier to carry a weapon, while teens who were threatened or injured were nearly six times more likely to take a weapon to school.

The study’s authors advise school districts to focus their violence prevention resources on those students who are most likely to bring a weapon to school. “By enhancing the sense of safety among bullied youth, they might no longer feel the need to engage in weapon carrying at school.”

The home-to-school gun pipeline

A 2014 Pew Research Center study found that more than a third of Americans with children under 18 have guns in their homes. And more than half of all U.S. gun owners do not safely store their weapons, according to Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Of the 30 guns confiscated in Charlotte schools, only seven were identified as stolen; most were traced to the home of the student’s friend or family member.

“I’ve heard kids tell me they can get a gun in twenty minutes if they wanted to get a gun.”

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Chief Johnny Jennings said at a press conference following last year’s shooting at West Charlotte High School.

The neighboring state of South Carolina reported three shootings in schools in 2020 and one in 2019. In 2021, there were nine, the highest number of school shootings in 47 years, according to an analysis of data from the Center for Homeland Security and Defense.

Community members were already troubled by what they viewed as increasingly unsafe schools but when a 12-year-old classmate shot and killed 12 year-old Jamari Jackson at Tanglewood Middle School in Greenville, they demanded action.

The day after the fatal incident, a group of Baptist ministers and other community leaders held a press conference. After a moment of silence to commemorate Jackson’s death, they demanded the state and school district install metal detectors to prevent such tragedies from happening in the future.

“We do realize that we will have mixed feelings on this issue, but we honestly cannot think of any other way to stop guns from entering our schools,” said the Rev. Dr. U.A. Thompson, an author, activist, seminary professor and pastor of Bride of Christ Baptist Church in Greenville.

Groups like the National Association of School Resource Officers have long argued that detectors are ineffective when it comes to discovering weapons. Even finding the right location poses a challenge since most high schools have multiple entry points and students and staff are adroit at getting around such devices. That skepticism seems to be backed up by a 2018 report from the School Safety Blue Ribbon Panel in Los Angeles, which found that the majority of weapons were discovered when students informed school officials, not by metal detectors or random searches.

Nonetheless, some members of Greenville’s community argue, in light of these gun tragedies, something has to be done. Organizer Traci Fant, of Freedom Fighters Upstate SC, knows that magnetometers tend to be used more in educational institutions with high numbers of students of color and can make schools feel more like a jail. Nonetheless, she believes they are the best way to deter school violence. “Our children’s lives have to mean more to us than just what something looks like,” said Fant, who, for years, has been calling for metal detectors in Greenville schools.

AI to combat guns in schools?

Schools across the nation are struggling to find the stymie the gun scourge. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Superintendent Winston initially floated the idea of providing all high school students with a clear backpack at a cost of $500,000 to the district. The idea was shelved quickly after angry parents blasted it as a costly, performative and perfunctory gesture that would do nothing to make campuses safer.

Gifford Law Center researcher Drane agreed. “There’s not a lot of data to suggest that they would be effective. You could put a jacket around a gun, put it in a clear backpack and successfully defeat that measure.”

Perhaps, in light of that reality, some of the nation’s school districts are exploring what they hope will be surer fixes. Following last year’s shooting that left four students dead and seven injured in Michigan’s Oxford High School, the Oxford Community School District invested heavily in new artificial intelligence technology and currently is testing out ZeroEyes and Evolv, separate AI software that scan security camera footage for weapons.

According to its website, Evolv technology is already being used in schools in Spartanburg, S.C, Champaign, Ill. and Fayette County, West Va. Both Evolv and ZeroEyes are free to the district for a limited period of time.

South Carolina’s Greenville school district also is looking into several different types of newly developed weapons detection technology that uses sensors and analytics rather than traditional metal detection to identify weapons.

The department of public safety’s Lassiter also heads the North Carolina Task Force on Safer Schools, consisting of volunteer students, parents, law enforcement officers and counselors. “Schools are a balance,” he said. “You’ve got to have security in a way that creates what feels like a safer environment but doesn’t turn the school into a prison. We want to have a comprehensive approach with universal measures that will work across the state.”

The group is in the process of rolling out a campaign that educates adults on how to better secure firearms in their homes and vehicles. The goal also is to remind them that the right to have firearms comes with a responsibility to make sure they are properly secured.

Limiting youth to access guns

Roughly 30 states and the District of Columbia have child access prevention statutes. While the specific laws vary state-by-state, the goal is to make it more difficult for children to obtain a firearm. In January, the Clark County school district in Nevada started including a notice in the packet of materials each parent receives during registration about how to safely store firearm, And last December, the Atlanta Public School district passed a resolution committing to work with health agencies and nonprofits on safe gun storage.

Gifford Law Center’s Drane said the crisis of guns in schools calls for the kind of broader policy response that the U.S. Congress and White House have failed to enact. “A number of studies showed that simply having stronger gun control such as universal background checks and safe firearm storage at home can be a deterrent. Cumulatively, policies like that are associated with reduced child access to guns and a decrease in youth weapon carrying.”

In North Carolina, Gov. Roy Cooper is requesting more than $38 million in next year’s budget to support violence education programs, school safety grants and community grants.

The school safety task force will launch Educating Kids on Gang and Gun Violence during the 2022-23 school year. The program incorporates short video clips and interactive presentations about the legal, physical and medical consequences of guns and gun violence.

“The goal is to make sure that kids truly understand the detrimental things that can happen to you, not just if you use the firearm but if you just bring it to school,” said Lassiter, the state’s public safety deputy secretary. “What are the things that would happen to you in the criminal justice system, what would happen to your life, and what happens to your education.”

A link between mental health, kids and guns?

There is an increasing recognition that school safety cannot be achieved through physical security measures alone. Health and school safety experts, including several researchers, have said the pandemic exacerbated what has been worsening mental health of youth. The Children’s Hospital Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry declared a national children’s health emergency last fall.

Mental health clinicians caution against assuming that everyone who shoots at a school is mentally ill because that hasn’t been medically proven.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that, in some cases, everyday disputes among teenagers are increasingly being resolved in more dangerous ways because troubled and/or frightened students — most of whom are not old enough to purchase a firearm — have a gun at the ready.

Addressing these vital issues requires more and better mental health resources such as school psychologists trained in prevention and mediation to help identify at-risk students and potentially violent situations. But there is a dearth of available mental health support in North Carolina schools, reflecting a nationwide shortage in that workforce.

The ratio of psychologists, school counselors and social workers to students is well above the levels recommended by the National School Counselors Association. For example, the association recommends one psychologist for every 500 students but the school psychologist at Mount Tabor High School serves roughly 4,000 students across four different schools. Gov. Cooper’s budget also includes increased funding for mental health services in schools and the task force is pushing to increase mental health staffing to meet or exceed the national standard.

The Giffords Law Center calls guns in schools “an unnecessary and significant threat to the safety of children.” As now former Charlotte-Mecklenburg School superintendent Winston said in his video message last December, the increasing number of such incidents requires an all-hands-on-deck response.