Two decades ago, it was common practice for the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption to advertise the faces of foster youth seeking permanent homes inside Wendy’s restaurants, on posters and tray liners underneath the chain’s signature square hamburgers.

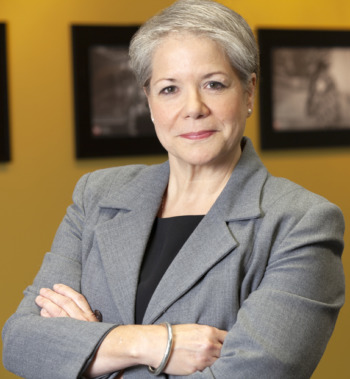

Rita Soronen, a longtime national child welfare advocate, had just taken over as president and CEO of the nonprofit charity named after Wendy’s founder Dave Thomas, an adoptee and outspoken supporter of adoption. She remembers distinctly when the organization got a distressing complaint.

“We got a call from a young woman who went into the restaurant, saw her face on a poster and was thoroughly upset, begging with us to please take it down,” Soronen recalled. “It immediately shifted my thinking about what are we doing here. Is this the best possible way to make sure that these children and youth can get adopted?”

Courtesy of Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption

Rita Soronen, president and CEO of the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption, warns of the potential harm adoption “heart galleries” can do to young people in the foster care system.

The foundation completely did away with public photo displays of kids for adoption. In fact, its internal research showed that it didn’t even work very well. The charity switched tactics and designed a new model in which full-time recruiters — with caseloads of no more than 12-15 foster youth at a time — search to find kids permanent homes.

It turns out the new model — known as Wendy’s Wonderful Kids — was much more effective.

Children who worked with a recruiter were one-and-half times more likely to be adopted than those featured in ads and up to three times more likely for older kids, according to the organization’s own research. In all, the new program boasts 11,000 adoptions since its inception in 2004 and works with several state agencies.

Federal law requires child welfare agencies to make an effort to place foster youth in permanent homes, and over the decades the vast majority have relied heavily on largely passive — and low cost — appeals to public sympathy much like the ads inside Wendy’s restaurants. Agencies across the country publish photos and personal information about foster kids in online galleries, newspapers, television news segments, social media and during in-person events.

But Soronen and other child welfare advocates warn of the potential harm these advertisements can do to young people in the foster care system and of the longer-term impact on the youths’ digital privacy. And initial evidence from a handful of states suggests that individualized approaches that focus on connecting the right children with the right families can be more effective — and ultimately save states money.

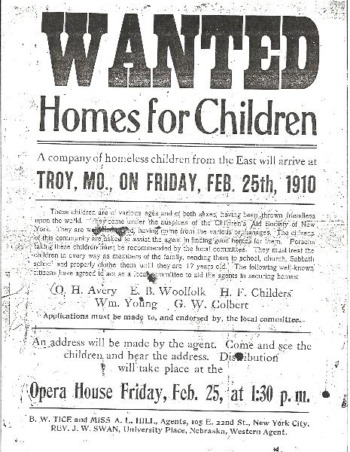

Wanted: Homes for Children

The practice of advertising children for adoption dates back to at least the nineteenth century, when orphan trains relocated a quarter of million children from New York to the west, advertising adoption events in local newspapers along the way.

Appealing to the public in its current form was borne out of the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, landmark legislation requiring child welfare agencies to make an effort to connect foster youth with permanent homes.

From that law, came the federally-funded and regulated national photo-listing website AdoptUSKids, where nearly every state’s child welfare agency posts photos of and basic information about foster youth available for adoption. There are 4,500 children listed and 2,600 families registered on the federal AdoptUSKids site alone, according to the site.

J.W. Swan/Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

A 1910 advertisement seeking homes for “a company of homeless children”

Bob Herne, national project director for AdoptUSKids, said opinions and best practices around photo-listings are an “evolving situation.” Some prefer not to include photos of foster youth with the profiles; other states don’t use them, saying photo-listing is outdated. Still others see photo-listings as a highly successful tool to find homes for kids.

AdoptUSKids doesn’t control what states post on the website — though it reviews profiles before publishing — it does offer a best practices guidebook, which offers tips and suggestions for writing “strength-based” profiles that include input from the youth.

“The more the youth is involved and expressing who they are, the better the type of narrative that you’re going to have,” Herne said.

In addition to posting on AdoptUSKids, many child welfare agencies create their own sites or partner with private organizations to showcase their available foster youth.

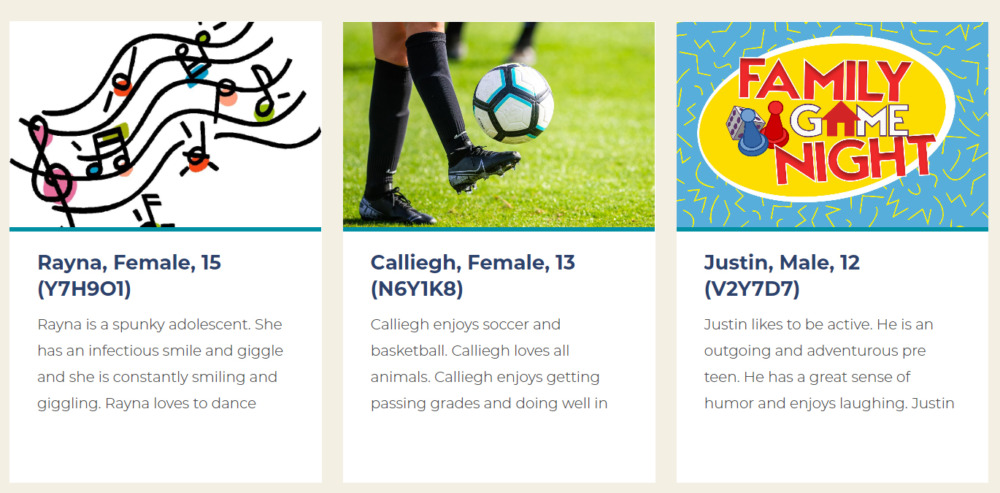

The “listings” vary by state, but most contain personal information such as the child’s name, age, race and any disabilities, Some sites include personality assessments of the child, their relationships with siblings and their hopes and dreams. Many include professional-quality photos and videos of the foster youth available for adoption known as “heart galleries.”

Child welfare agencies and other groups regularly share youths’ information and portraits on social media, Twitter and Facebook, where there are also adoption groups and individuals who are free to swap and share images and information about children available for adoption:

- A 13-year-old boy from Florida is said to be “caring, funny” and hopes to one day be a welder.

- In Los Angeles, a 17-year-old girl is described as being a cheer captain and prefers parents of “Hispanic ethnicity, so that she can remain tied to her heritage.”

- A 4-year-old Alabama boy “can be stubborn when he does not want to be bothered.”

Another long-standing practice has been featuring “Child of the Week” segments on local television and in newspapers. Some states have now turned to social media, too. The Georgia Division of Family & Children Services, for example, recently tweeted a portrait of two siblings who “enjoy listening to hip hop music, playing UNO, and spending time together.”

“How come nobody wants me?”

Deborah Shropshire, director of Oklahoma Child Welfare Services, can recall a handful of foster youth whose stories shared in media segments went viral and the disappointment they felt when after all that attention they still weren’t adopted.

Courtesy of Youth Law Center

Youth Law Center Executive Director Jennifer Rodriguez, a former foster youth, has heard both sides of the debate over “heart galleries.”

“At the end of the day that kid doesn’t get a family, and they ask you ‘how come nobody wants me?'” Shropshire said. She couldn’t cite any hard data, but said anecdotally, as a result of not being adopted, “we’ve definitely seen kids regress.”

Kelsey Vander Vliet Ranyard, director of advocacy and policy at AdoptMatch, a private adoption nonprofit, is also concerned about the safety of the foster youth featured in online photo displays.

“These kids’ pictures are shared all over the internet,” she said. “It’s kind of scary to know who could be looking at these children.”

While there isn’t direct evidence that photos on social media have enticed dangerous people to track kids down, agencies do struggle over what to do with a youth’s digital footprint. When they grow up, attend college or are having families of their own, what sort of impact does having their foster youth journey housed forever on the internet have on them, Shropshire wondered.

Youth Law Center Executive Director Jennifer Rodriguez, a former foster youth, has heard both sides of the debate over “heart galleries.” Her organization does not have an official stance on the issue.

Agencies that publicly display photos and stories of youth argue the advertisements are a heartfelt and compelling way to attract much-needed attention to adoption and posit that people are more likely to become foster or adoptive parents if they can put a real face and story to the child, she said.

Courtesy of Think of Us

“Imagine a young person who ended up getting adopted from that situation, and it worked out,” said Sixto Cancel, a former foster youth and CEO of the national child welfare advocacy organization Think Of Us. “Was it worth it? Yeah.”

On the flip side, she’s heard advocates and foster youth critique heart galleries as portraying children as “adoptable animals in a shelter which can feel demeaning, particularly when there are so many Black and brown children featured.” They also say the process can be emotionally bruising for vulnerable children.

For Rodriguez, “highlighting resources and adoptive parents, as many quality parenting initiative sites do, can be an important, less potentially problematic method to connect with the public and potential parents.”

It’s a complicated issue, with many child welfare organizations and nonprofits unwilling to take an official position. In addition to the Youth Law Center, Annie E. Casey Foundation declined to comment on the debate and a representative of the National Association of Counsel For Children said the organization takes no official policy. Even the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption, which ended its practice of publicly displaying children for adoption years ago, still works with agencies and nonprofits that do. And the Dave Thomas foundation continues to highlight success stories of youth who’ve found permanent homes.

Sixto Cancel, a former foster youth and CEO of the national child welfare advocacy organization Think Of Us, said he is on the fence about public displays but as a one-time foster parent recruiter he has personally seen the benefits of heart galleries.

“Imagine a young person who ended up getting adopted from that situation, and it worked out,” he said. “Was it worth it? Yeah.”

Connecting families to children

Several states — including Oklahoma, Ohio and Florida — are exploring alternatives to publicly advertising youth who are available for adoption such as individually matching families and youth.

In 2019, Oklahoma Child Welfare Services shifted completely away from public displays of foster youth in favor of Wendy’s Wonderful Kids’ child-focused recruitment model.

When Shropshire, the agency director, started out in the child welfare field decades ago, she said the public wasn’t aware of how many foster youth needed a home. Public displays brought foster youth into the spotlight and now most people have at least a passing understanding of the need for more foster youth adoptions, she said.

For Oklahoma, raising awareness was no longer the issue. Shropshire said 95% of kids eligible for adoption are adopted by their foster family.

The remaining children typically have higher personal challenges and mental health needs. And over the years, the agency noticed that most prospective adoptive families on the waitlist didn’t “match” this segment of children, she said.

Shropshire pointed to the research from Wendy’s Wonderful Kids that showed high needs kids do better in a targeted approach to source parents, by searching for parents the kids have had a previous connection with, like a coach, teacher or neighbor. With that in mind, the agency decided it was more effective to actively recruit parents for youth who couldn’t be adopted by their foster families

For cash-strapped agencies, hiring even one full-time recruitment employee might not be realistic, which is why Wendy’s Wonderful Kids will pay for hiring and training staff for the first couple of years with the idea the agency will source funds to continue the program afterward.

For states willing to take on the investment, the long-term savings can be huge, said Soronen.

Courtesy of Ohio Department of Job and Family Services

Ohio posts foster youth for adoption profiles online but no longer includes photos of the kids, using instead stock images of things like animals, sports or landscapes.

In Ohio, for example, Wendy’s Wonderful Kids program placed 667 kids in permanent homes from 2015 to 2021. The state spent $3.8 million on the program but saved a total of $133 million in payments to foster families and group homes, according to a cost analysis by the nonprofit. Ohio posts foster youth adoption profiles online but no longer includes photos of the kids, using instead stock images of things like animals, sports or landscapes.

And Florida now uses predictive analytics, analyzing data and studies about previous successful foster youth adoptions to match adoptive families with children and teens, in addition to heart galleries.

Thea Ramirez is the founder of the nonprofit Adoption-Share, which she said works with Florida and Georgia’s child welfare agencies to match families with adoptable kids.

The reason so many foster kids aren’t adopted, she said, is because they fail to match compatible families to the kids — many of whom have high needs and have experienced a lot of trauma.

For her, the answer is predictive analytics — another controversial topic in child welfare — for weeding through the potential parents to find the ones that are most likely to succeed with high-needs older kids.

In Florida, the only state to fully adopt her organization’s technology, she said, predictive analytics led to 310 adoptions in three years, and, based on the cost of caring for kids in the foster care system, saved the state millions of dollars .

She points to research that showed there are a lot more families looking to adopt than there are foster kids.

“The issue is not scarcity,” she said. “It’s connection.”

***

Share your story

Do you have personal experience with adoption or foster care? Share your story or thoughts with us or email mbloom@csjournalism.org.

We won’t publish or share your information with anyone unless you tell us it’s okay to do so.

***

Brian Rinker is a San Francisco-based freelance writer and journalist. He covers public health, child welfare, digital health, startups and venture capital. His work has been published by Kaiser Health News, Health Affairs, The Atlantic, Men’s Health and San Francisco Business Times. Brian received master’s degrees in journalism and public health from UC Berkeley.

Youth Today receives support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Youth Today is solely responsible for all content.