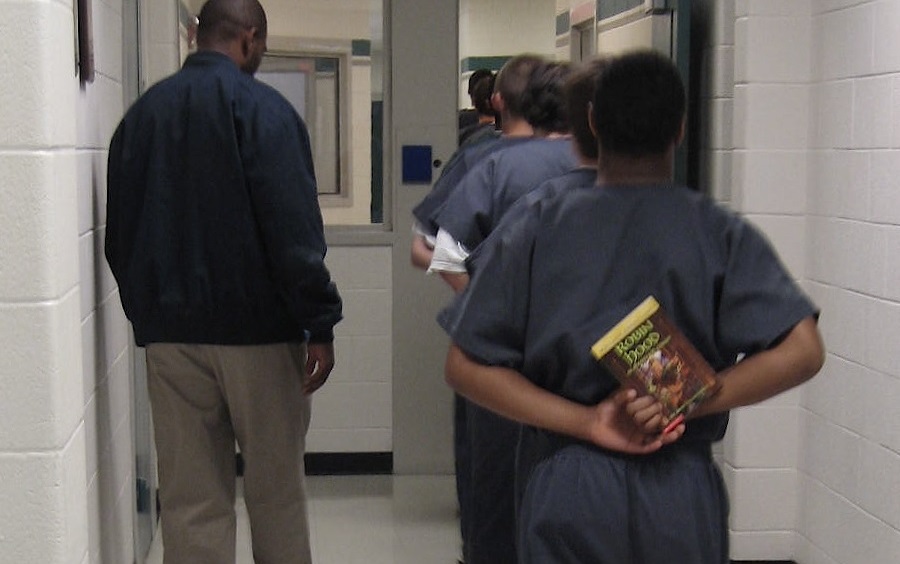

Most of the 50 states have clearly designated which agencies are in charge of hiring teachers for incarcerated juveniles, creating teaching curriculum and other education services. But how and by whom that instruction gets delivered varies substantially from state to state and locale to locale, resulting in a fragmented system that generally provides inferior instruction, according to a recent report from Bellwether Education Partners.

“Within states, governance models assigning responsibility to deliver education can range from state agencies that contract with [local education agencies], public charter schools, or education nonprofits, to systems where the state’s custodial agency provides for and oversees the education program,” those researchers wrote in “Double Punished: Locked Out of Opportunity.” “There are also many models in between where the state may assign responsibility to a county or other municipal entity or to the geographic school district where the building is located.”

Focused on “governance, accountability and finance,” the report did note what researchers said were several bright spots, including in data collection that reflects how well juvenile education programs are performing; and in establishing policy and programs for how juveniles might either graduate from high school or obtain their high school equivalency diploma.

Nevertheless, the researchers reached these, among other, less positive conclusions:

- In at least 28 states, separate agencies provided education services in local detention centers and state-run juvenile justice facilities.

- There are conflicting requirements for juvenile justice education programs to submit data to multiple government agencies, which can weaken “accountability incentives and result in programs pursuing many more goals than is feasible to achieve.”

- Measures to indicate the quality of education that juveniles receive do not reasonably apply to those incarcerated students, “mostly because many students are incarcerated for short and unpredictable amounts of time. As a result, we know very little about whether these programs are achieving the goals they set for themselves or that are set by state policymakers.”

- In 17 states, local education agencies that provide instruction for incarcerated students are incentivized to provide the legal minimum of education service. That’s partly because those local agencies wind up overseeing education programs for youth who are not residents of their school districts; and are not required to be accountable for how those youth are taught.

“Although juvenile justice education programs are operated by local education agencies (LEAs) and are called schools,” researchers wrote, “the waivers, exceptions, and fragmentation of leadership in juvenile justice settings makes it nearly impossible for educators to create conditions that approach those of ‘a school,’ let alone to provide high-quality education programming.”