A high school junior steps out from his silver BMW not far from his school’s track and field on Albuquerque’s working-class west side.

Andrew Burson, 16, is there because another kid, Marcos Trejo, 14, stole something from him — a ghost gun, witnesses told police. So he pins Trejo against a fence and demands he give it back.

A confrontation ensues. Trejo runs. Burson pursues, then Trejo allegedly turns and fires five bullets into Burson.

Three months later, Trejo is in a juvenile detention center awaiting trial for murder and Burson’s family and the community are left reeling. The tragedy is one of many in a country where firearms are the leading cause of death for kids up to age 19.

“It’s really been hard. My wife got really sick,” said Al Burson, Andrew’s father. “And not only my wife and I and his brother, but the extended family — grandmothers, aunts and uncles — were devastated by this. And his friends too. His friends still come and visit.”

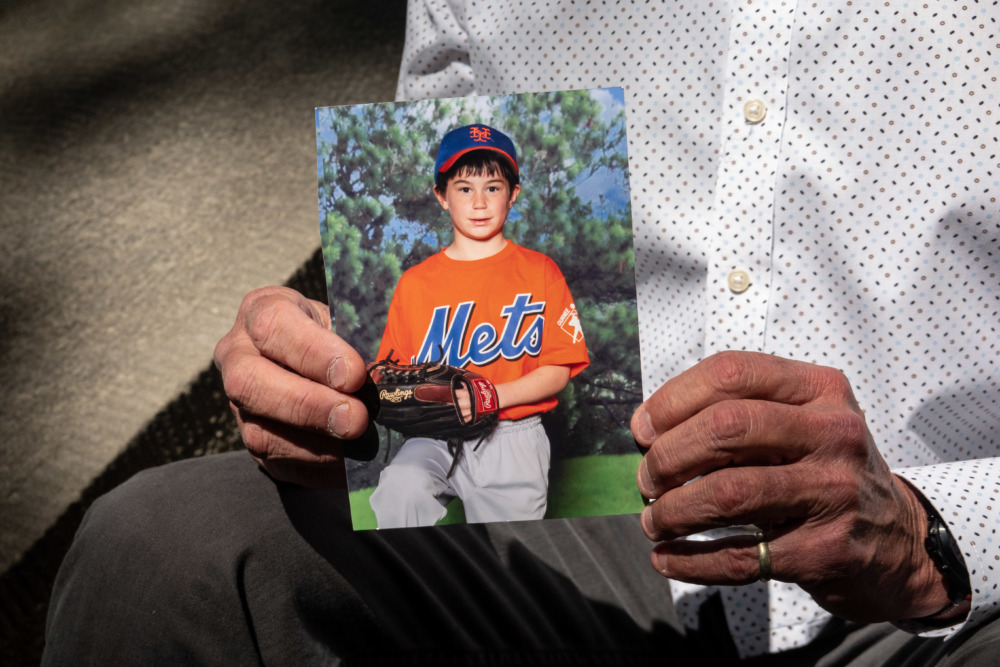

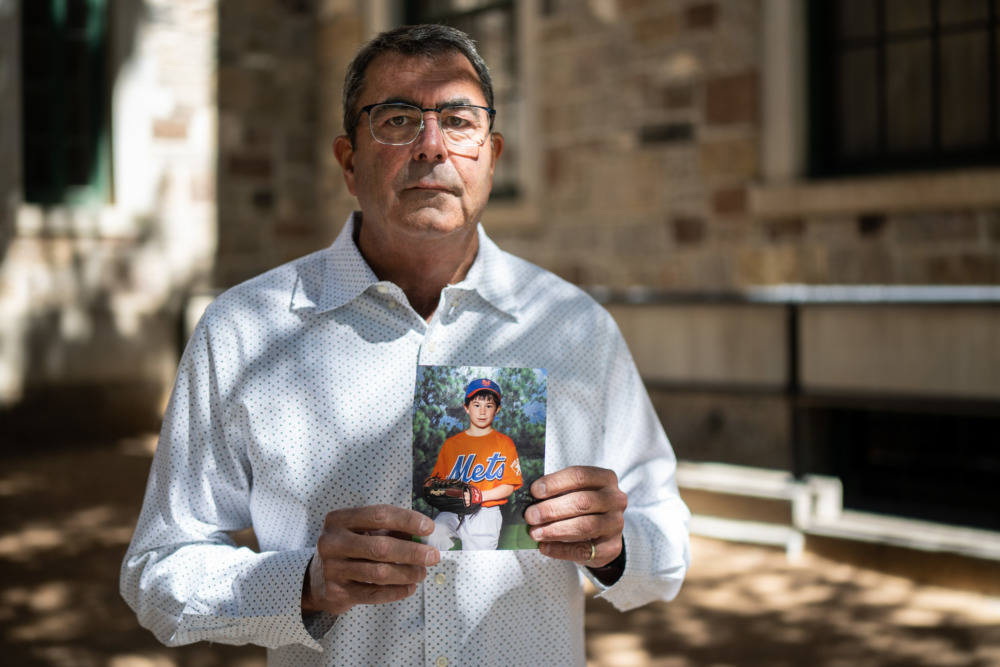

Ramsay de Give

Al Burson holds a photo of his late son, Andrew Burson, in Santa Fe, N.M. on May 25, 2022.

Two other children told police the fight started over the weapon used to kill Andrew Burson: an unmarked, unserialized handgun bought on the internet. An Albuquerque police spokesman said they never recovered the weapon, so the department was unable to confirm the type of gun used.

Ghost guns — so-called because they are nearly impossible to trace — are sold in parts and assembled by the buyer. Until recently, they were not classified as firearms, meaning there were no background checks and dealers didn’t have to be federally-licensed.

That has opened the door for traffickers, teens and people with felony records to get ghost guns.

“We’ve seen this is a major nexus for gun trafficking,” said David Pucino, deputy chief counsel at Giffords Law Center in New York and an expert on ghost guns. “It’s really a product that was designed to facilitate that.”

In April, the Biden administration approved a new rule classifying gun kits as firearms. The rule change requires sellers to conduct basic background checks and be federally licensed.

Gun control advocates, law enforcement and elected officials welcomed the rule change, but most said they think it will have little impact in most states since ghost guns comprise a tiny fraction of the weapons fueling gun violence in New Mexico and across the country.

Still, Pucino called the new rule “incredibly welcome and a huge win for public safety.”

Miranda Viscoli, co-president of New Mexicans to Prevent Gun Violence, was less optimistic.

“I’ve asked kids how fast they could get a gun off the street, and they say ‘Eh, 20, 30 minutes,’” she said.

Lanae Erickson, a lobbyist with the Washington D.C.-based Democratic think tank Third Way, said many people are frustrated with the lack of action on gun control in Congress.

“The Biden administration went basically as far as they could with executive action,” said said. “I think a lot of folks recognize the administration’s hands are tied.”

Ghost gun trend collides with youth gun culture

From 2016 through the end of 2021, the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms and Explosives received more than 45,000 reports of suspected ghost guns recovered by law enforcement nationwide, including nearly 700 linked to homicide or attempted homicide investigations, according to Erik Longnecker, a spokesman for the ATF Phoenix division.

Most ghost gun seizures have been in California or New York. Although they are on the rise in New Mexico, which has the seventh highest gun death rate in the country — mostly from suicide — fewer than 100 ghost guns were recovered between between 2016 and 2021.

Carolyn Kaster/AP

A 9mm pistol build kit with a commercial slide and barrel with a polymer frame is displayed before President Joe Biden and Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco speak in the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington, April 11, 2022, to announces a final version of its ghost gun rule.

But when crime trends change on the coasts, it often takes years for New Mexico to follow suit, said Bernalillo County District Attorney Raul Torrez, whose office is prosecuting the case against Trejo.

“Right now, the crime guns we see on the streets of Albuquerque are not connected with ghost guns,” he said. “But if we follow the national trend, I think this will change over time.”

Indeed, ghost guns appear to be woven into local youth gun culture.

Nick Hernandez graduated from West Mesa High, where Andrew Burson was a student, in 2019.

Hernandez, now 20 and a college student, said the first time he saw a classmate bring a gun to school was in the seventh grade. The second was during class his junior year.

“It is common,” Hernandez said. “You kind of get used to it.”

Another time, Hernandez said a friend tried to sell him a “ghost glock” — a term he heard from other students as well.

“A lot of my friends talk about them,” he said. “They would mention one of their buddies has one, or they’re getting one.”

Hernandez said he thinks the youth gun culture he experienced stems from poverty.

“These students are in these conditions and they have no other outlet to express themselves,” he said.

Andrew Burson’s father said he doesn’t believe his son bought a ghost gun. But two witnesses told police otherwise.

One said Andrew Burson posted on Snapchat the day before he died: “Some fool stole my gun, no big deal, just a minor setback,” according to Trejo’s arrest warrant.

Cycle of outrage and inaction

Albuquerque Police Department spokesman Gilbert Gallegos declined an interview with Albuquerque Police Chief Harold Medina and homicide detectives to discuss Burson’s killing and the role of ghost guns in local crime. The city also declined an open records request for the police report of Andrew Burson’s death.

Trejo’s attorney, Todd Farkas, a public defender, declined an interview, but wrote in an email: “I think it is very sad that the state is seeking adult sanctions on a 14 year-old.”

Andrew Burson was not the first Albuquerque student killed on or near campus recently.

The shooting death last year of 13-year-old Benny Hargrove, an eighth grader at Washington Middle School in Albuquerque, provoked outrage and calls for legislative action to hold parents liable for not securing firearms that are later used by children to commit a crime.

But despite Democrats controlling all levels of state government, the measure failed to clear the Legislature.

“We never got a clear answer to why that bill didn’t pass,” said bill’s main sponsor, Rep. Pamelya Herndon, a Democrat from Albuquerque.

She said she intends to tackle state-level gun reform, including ghost gun regulations, again during the 2023 legislative session.

Albuquerque Mayor Tim Keller declined to be interviewed for this story. A spokeswoman for the mayor, Ava Montoya, said in a statement that gun violence cannot be fixed by any single entity or action.

“Any step toward common sense gun laws, like the federal ghost gun rule, is welcome progress,” she said.

In 2020, the city created a violence intervention program that sends specialists to hospitals in the wake of a shooting to peaceably intervene.

Some critics argue that the program doesn’t address the root causes of violence, but Angel Garcia, a social services coordinator with the program, said he hasn’t “met one kid yet who’s been hardened to the point where they’ve said, ‘No I don’t want your help.’”

Ramsay de Give

Angel Garcia, the social services coordinator for the Albuquerque’s violence intervention program, photographed in Albuquerque, N.M. on May 17, 2022.

Garcia, who grew up in Los Angeles in the nineties, said he started carrying a gun at the age of 12 after joining a gang because he had to walk past six rival gangs and was tired of getting beaten up on his way to school.

He spent 12 years in prison before taking a job with the city trying to help people walk away from a life of violence.

“Honestly, I just don’t think it’ll make a difference,” Garcia said of the Biden rule on ghost guns. “There’s people out there that have bazookas and grenades, to be honest with you. If somebody wants a gun, they’re gonna get one.”

Responding to trauma and grief

Albuquerque Public Schools spokeswoman Monica Armenta declined interview requests with West Mesa High School’s principal, teachers, counselors and the superintendent.

The district has shared little with students about Andrew Burson’s killing, citing privacy concerns for the victim’s family.

But experts on childhood trauma after school shootings say transparency is key for healing.

Sandy Graham-Bermann, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, said that includes sharing facts about what happened, how police are involved, locations of vigils and opportunities for students to ask questions directly.

“The families are now terrified — ‘Would my kid be shot tomorrow?’” she said. “It affects the family, and then it affects the community.”

Melissa Brymer, director of terrorism and disaster programs at UCLA-Duke National Center for Child Traumatic Stress, said it’s important for the district to make a map of the people who knew both students, including friends, lovers or teammates, so that the school can offer counseling and support.

“In the end, you have people mourning the loss of their friends, the loss of their family member, and many of those questions go back to how much they miss that person,” Brymer said. “As we’re focusing on the trauma, we also need to focus on the grief.”

For Al Burson, who said he support’s Biden’s new ghost gun rule, he’s just trying to get by after the death of his son.

“We’re still in the grieving phase, and sometimes, it’s still a shock,” he said. “What hurts most is that I won’t see what he’ll become. I knew what he was, but I won’t be given the chance to see what he’ll become. And I think that’s the thing that affects me the most. And it wasn’t an accidental death either: His life was taken by someone else.

“I don’t want anybody to ever have to go through this.”

***

Michael Gerstein is an award-winning freelance journalist based in Chicago. He’s written for the Associated Press, WBEZ (Chicago’s NPR station), The Detroit News, the Santa Fe New Mexican and other news outlets.

Ramsay de Give is a freelance photographer based in New Mexico.