COLUMBUS, N.M. — Maria Constantine manages the Columbus Village Library, which has the only 24/7 open-access high-speed internet connection within miles of the small New Mexico border town of 1,600.

“When I first got here, I used to shut off the Wi-Fi at night,” said Constantine, who started the job in 2018. “Then one night, I saw a kid with his mom in the car, doing homework. I’ve left it on for 24 hours since then.”

New Mexico consistently ranks toward the bottom among states for internet access, and nearly 25 percent of students lack access. Columbus, New Mexico, is located in Luna County, an area about as large as Delaware and Rhode Island combined that is home to about 25,000 people scattered between Columbus, the town of Deming and miles of rugged desert.

The library, town hall and school are all connected to a single fiber-optic cable that was installed several years ago to serve the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol at the Columbus port of entry. The rest of the county relies on spotty cellular service, satellite and DSL, a technology introduced in the 1990s that uses telephone wires to connect users to the internet.

The lack of fast, reliable connection hinders residents’ ability to access education, employment, health care, information, benefits and services, especially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Children and youth under 25 have been particularly impacted, since most education has switched to a hybrid model, requiring attendance in video classrooms.

Paul Ratje/©Paul Ratje

Librarian Maria Constantine poses for a portrait outside the Columbus Village Library in Columbus, N.M., on Aug. 23, 2021. The library recently installed Wi-Fi boosters to extend service across the main street and into the park as a community service benefiting both kids and their parents.

“Not having a good connection or having internet service at all is a huge barrier for a student’s overall academic success,” said Crystal Gonzales, lead equity liaison for the Deming Public School System. “It’s a significant equity issue. Students are facing enough challenges and working hard to prevail — they need reliable and efficient connectivity and technology to work for them.”

But outdated infrastructure isn’t the only barrier to internet access, which is increasingly necessary for school, employment and accessing benefits. The cost of even slow service is out of reach for many, and one in six local students live in Palomas, Mexico, and commute over the border for school.

“These are American citizens with a Constitutional right to an education,” said Ben Glickler, director of technology for Deming Public Schools.

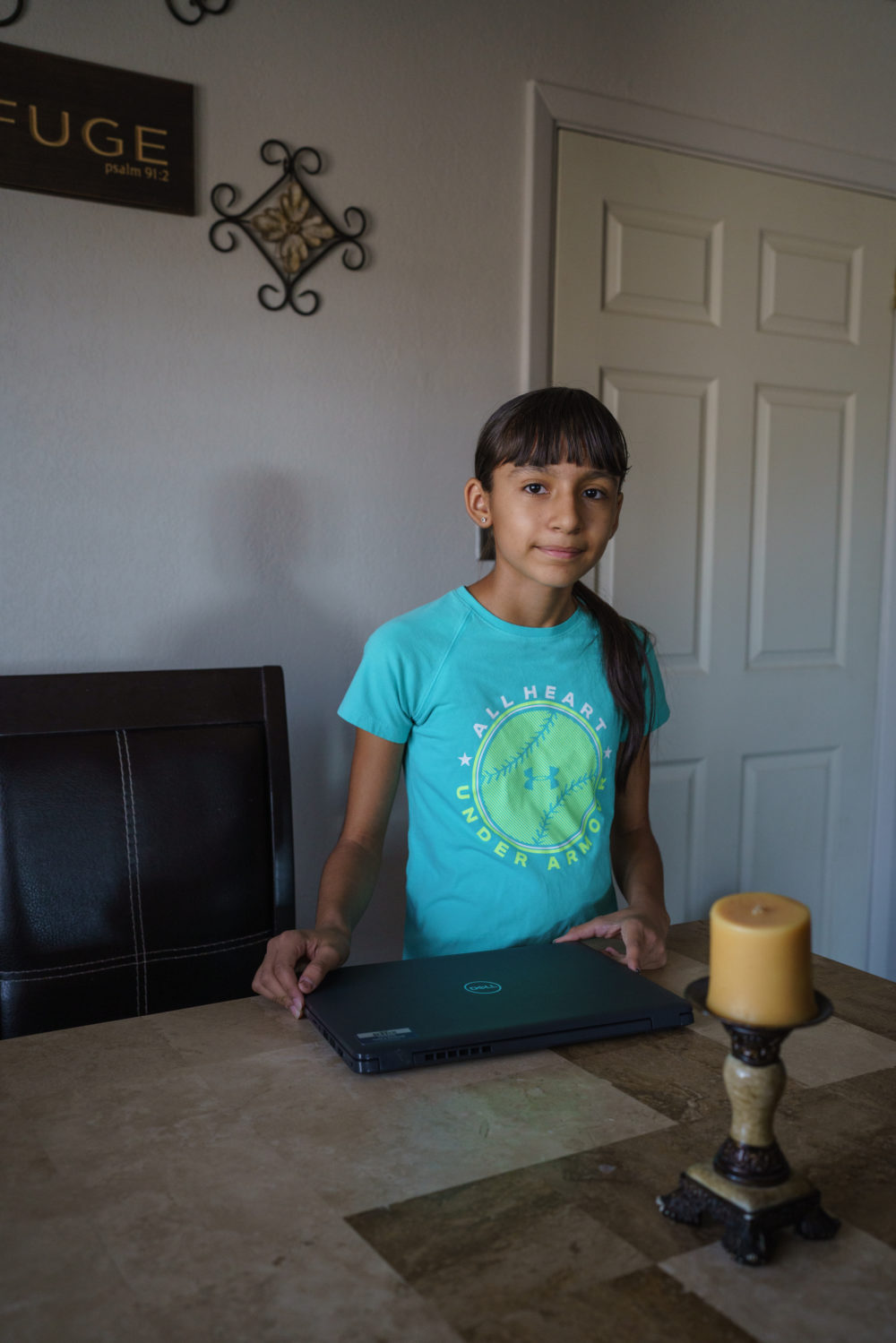

Paul Ratje/©Paul Ratje

Sioney Amaya, 12, shows her school-issued laptop inside her home in Columbus, N.M.,, on Aug. 3, 2021. She and her sister have struggled with slow internet speeds when completing online classes throughout the pandemic.

But delivering on that right isn’t simple. When the schools shut down in early 2020 for the pandemic, the district scrambled to identify students with limited or no connectivity, Glickler said.

At that time, the federal government relaxed its definition of “campus” to include off-site areas such as children’s homes, allowing schools to provide hotspots using federal e-rate funds. In Deming, all students were provided with laptops and those without connectivity received hotspots in an attempt to keep them up to speed with the rest of their classmates.

Many of those hotspots were carried over the border into children’s homes in Palomas or out into ranching communities.

But the further away from central Deming, the less likely kids are to have access to internet infrastructure. Cellular service in border communities is purposefully weak by international agreement. Once across the border, U.S. cellular reach drops dramatically. Video schooling for kids outside of Deming has been plagued by either significant lag time or complete lack of connectivity.

“Sometimes when the internet didn’t work in my house, I had to go to the library to see my classes and do my homework,” said Delanie Amaya, 10, of Columbus, who visits the library regularly with her family. “When we go, there were the same kids there because they didn’t have internet at home.”

An April 2021 ruling by the state of New Mexico mandates that all school districts must provide technology and high-speed internet access to their students, specifically targeting the historically underserved Hispanic and Native American populations.

The FCC defines high-speed internet as anything above 25mbps (megabytes per second).

The highest available speed in Columbus is 20 mbps at $75/month. With a staggering 44% poverty rate in the village and an average household income of less than $25,000 annually, internet is an unaffordable luxury for many.

Paul Ratje/©Paul Ratje

Delanie Amaya, 10, poses for a portrait outside her family’s home in Columbus, N.M., on Aug. 3, 2021. She says the family’s internet service, which is received through the satellite dish on her roof, can make completing her online classes challenging because of the outages and slow speeds.

The new federal infrastructure bill provides funding to rural areas lacking broadband. But the criteria are often too restrictive for a region that less than 100 years ago had free movement between countries.

“A lot of our families have been here for generations,” said Ariana Saludares, a Deming mother of two and co-founder of Colores United, a local aid organization involved in child welfare. “The borders moved. We didn’t.”

Federal funding cannot be used outside of the United States, even if in direct support of U.S. citizens. This creates a catch-22 for the school district, which is required to provide high-speed access to its students, many of whom live in Mexico.

Smaller vendors have erected their own cell towers along the U.S. side of the border that re-broadcast and resell the reach of American cellular networks into Mexico. These services are still relatively expensive and inconsistent.

During the pandemic, Deming Public Schools turned into giant open access hotspots for those that could get there. Now, with most learning back in person, kids still do the majority of their work on school-issued laptops, which means even the school’s fiber-optic connection isn’t enough.

“We’ve hit our maximum bandwidth every day since we got back to school in April,” said Glickler.

School officials know their challenges are unique, and are exploring how to stretch federal funding and creatively apply less restrictive state funding. For example, school leaders are exploring whether federal money can be used to subsidize home internet service, or if they can build their own cell towers.

The district is also working with the library and county to increase internet accessibility. The library recently installed Wi-Fi boosters to extend service across the main street and into the park as a community service benefiting both kids and their parents.

“We get people parked in cars around the library at all hours, doing homework, paying bills, looking up addresses and downloading movies,” said Constantine. “But it’s not easy to do all that sitting in a car, often on a phone.”