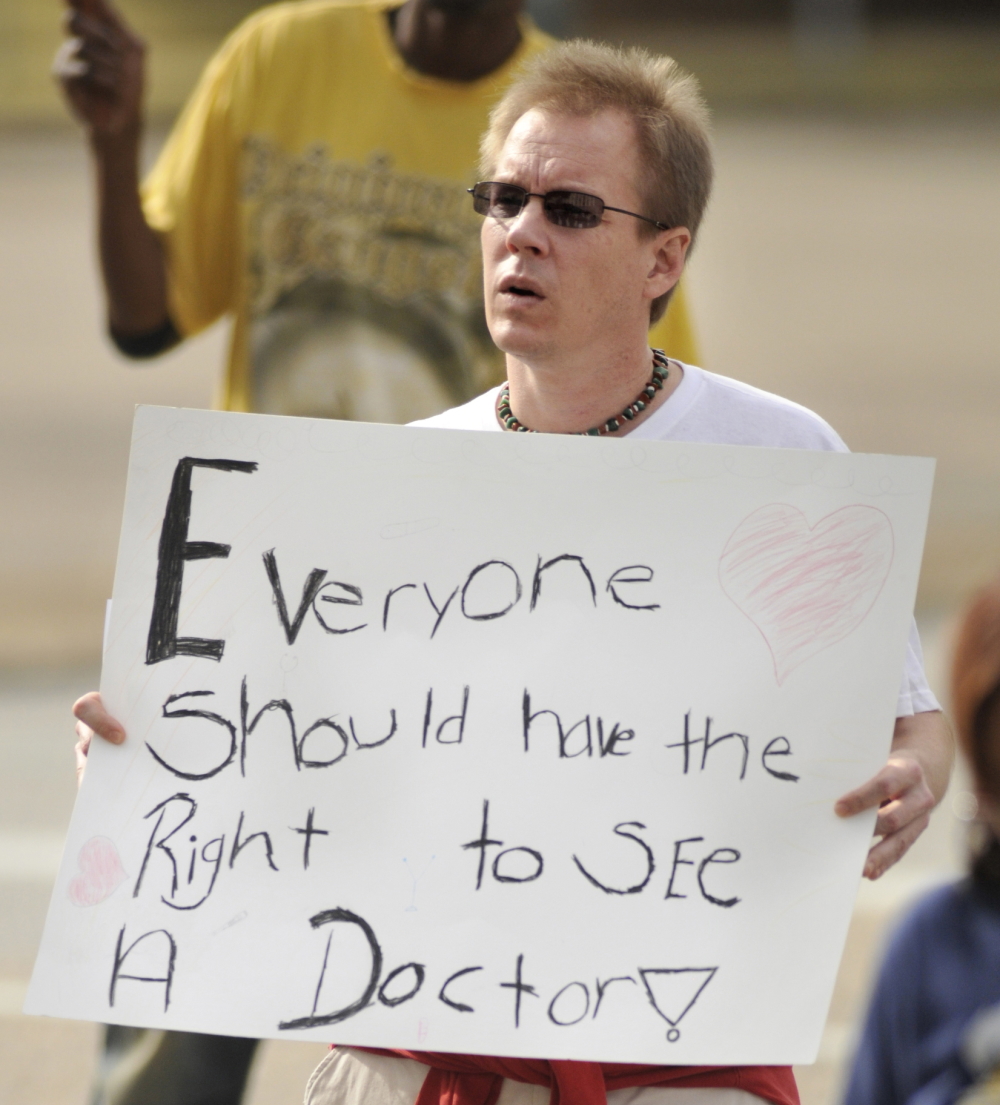

Lloyd Gallman/Montgomery Advertiser, AP

In 2013, Alabamian Ray Ables rallied at the Alabama State Capitol in support of the landmark Affordable Care Act. In 2021, 69% of polled Alabamians said they want their state lawmakers to adopt that act, including its provisions for low-income working people.

In largely rural northeast Alabama, a certified nurse’s assistant juggles a side gig as a dog-groomer to make ends meet; a free medical clinic’s executive director oversees a team of volunteer physicians who treat the uninsured; a hotel laundress and many of her female co-workers earn too little to afford private health insurance but too much to qualify for Medicaid, the state and federally-financed health insurance for low-income workers and jobless poor people.

All three women are troubled that Alabama is one of 12, mainly Southern states that have refused to buy into the 2010 Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, 90% of which is paid for by the federal government.

Southern states that have implemented that landmark law, also known as Obamacare, saw their spending on Medicaid drop by up to 4.7% between 2014 and 2017, according to a May 2020 Commonwealth Fund analysis. If Alabama had adopted that expansion, a projected 340,000 workers would have gained medical coverage and 28,500 jobs would have been added to the economy, according to a May 2021 Commonwealth Fund report also showing that roughly 470,000 Alabamians were uninsured in 2019.

Of Alabamians polled in January 2021 by the nonpartisan Cover Alabama Coalition of 93 consumer, health care, business and other groups, 69% said they want state lawmakers to approve the Medicaid expansion. But ahead of that public support for expanding Medicaid, many Alabamians viewed the program as “poorly run and poorly facilitated and, honestly, kind of a bureaucratic mess,” said Jane Adams, campaign director for Cover Alabama. She faults state lawmakers, she added, for perennially underfunding and devaluing the program.

In March 2021, Republican Gov. Kay Ivey and other state leaders said they were examining expansion incentives that are included in coronavirus relief funding.

As legislators debate whether Alabama will join the 38 states that have implemented the Affordable Care Act, that aforementioned nurse’s assistant, free clinic director and hotel laundry worker said they have their own stories to tell about the myriad costs and harmful effects of not having health insurance.

MCKENZIE CLARK IS A NURSING ASSISTANT, PODCASTER AND ACTIVIST

An electrolyte deficiency that Mckenzie Clark suffered when she was pregnant strained her heart. After being treated in a hospital for that ailment, she began experiencing severe pain that radiated from her neck down through her back. She wasn’t sure if it was related to that deficiency or a whole new problem.

“I was still working a dangerous amount of hours for a pregnant person,” Clark, 24, said. “I actually jeopardized my life because I worked so much. It was a difficult time.”

She fretted that telling her doctor about that persistent, shooting pain would not matter, given what she, a Black patient and nurse’s assistant, knew about race-based disparities in health care and health outcomes. One study found that half of white medical students believed, among other myths, that Black people had thicker skin, allowing them to endure more pain; those and other biases have resulted in Blacks being denied pain care for the same illnesses for which whites received pain care.

Additionally, in Alabama, Black mothers were 2.5 times more likely to die in childbirth than white ones, according to the most recent Alabama Public Health Department analysis; and Black infants were twice as likely to die as white ones. But when Black infants were cared for by Black doctors, their mortality rate, compared to the mortality rate for White infants, was halved, according to a 2020 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Those hard facts aside, said Clark, host of the Take Care, Black Etowah podcast, she’d experienced firsthand the raised eyebrows and frowns of some people in some medical offices who’d assumed she didn’t have money. “Not everyone was mean, but I didn’t feel supported in some environments,” said Clark, who also groomed dogs, for pay, during her pregnancy.

Not until her boyfriend, who’d lost his job as a software programmer, moved in with her and she was supporting both of them, did she financially qualify for Medicaid. By then, Clark, who’d been fractionally above Medicaid’s poverty line before that move-in, was five months pregnant and heading for her first prenatal exam.

“The doctor asked why I waited so long to come in,” Clark said. “He thought I was just being irresponsible. But I told him I couldn’t afford it.”

For that reason, and because she was afraid her physician would assume she was exaggerating, she didn’t bring up the neck and back pain, Clark said.

But when, during her seventh month of pregnancy, those shooting pains got worse, Clark worried that she and her baby might be at risk. Fearful, she returned to her obstetrician’s office.

“The nurse said it was just round ligament pain,” said Clark, summing up how that frontline health worker dismissed her concern as baseless. “But I was in school then, learning about the different feelings in the body and what they might indicate. This was not round ligament pain. She refused to take the time to believe me.”

So, through the remaining month of her pregnancy, Clark endured the pain.

When she delivered a healthy baby girl, who’s now 22 months old, she said she felt lucky. But she thinks about other pregnant people who also need more precise, compassionate care, especially the ones without insurance and access to health care providers who accept uninsured patients.

To Clark, accepting Obamacare’s provisions for expanding Medicaid is the absolute least lawmakers can do to help address health care problems in a state where such crises abound in areas ranging from mental health care to elder care to prenatal and pediatric care. Because only 16 Alabama counties have practicing obstetrician-gynecologists, more than half of the state’s pregnant women have to drive more than an hour for care.

Also, the state has disproportionately poor outcomes for Black mothers and babies and for a racial diversity of poor, rural mothers and babies.

“Medicaid expansion should have happened a long time ago. It’s the bare minimum. And it’s the easiest [to adopt] because the federal government is already offering the money,” Clark said.

Last summer, the Gadsden City Council appointed Clark, a Black Lives Matter organizer, to an advisory sub-committee that makes recommendations on everything from proposals to move a Confederate statue out of downtown to policies on decent, affordable housing. Researchers have listed earning an adequate income and living in affordable housing in good repair as aspects of good preventative health care.

Clark now is studying to be a physician’s assistant. and raising her daughter where she grew up. “I like it here. I can longboard downtown. I know everybody. But there aren’t a lot of opportunities,” she said. “My biggest thing is trying to make equitable economic opportunities for the kids in this city to be able to stay here.”

That includes access to quality health care.

FORMER NURSE JOAN JONES IS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF A FREE CLINIC

At Etowah Free Community Clinic in Etowah, Ala., Joan Jones’ patients sometimes have become her friends. One of those newfound friends brought magazines to Jones, that clinic’s executive director, when she was hospitalized for a few days earlier this year.

“She didn’t have the money to spend on extras like that. It meant a lot for her to come,” said Jones, 63, who previously spent 44 years as a pediatric nurse in neighboring Gadsden, Ala.

In 2015, she took the helm at the Etowah clinic, where volunteer physicians and other clinicians see uninsured patients from throughout Etowah County, which counts roughly 104,000 residents.

“I would love to be able to go in and input free clinics in each and every county,” said Jones, whose clinic targets the county’s roughly 25,000 uninsured individuals.

Those 19- through 65-year-old patients sometimes are healthy. But a disproportionate number of them have been diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disorders, high cholesterol and other chronic or acute conditions. If a patient needs a referral, the clinic partners with local specialists who also provide care. The clinic provides free psychological and dietary counseling, budgeting classes and other offerings tied to health overall.

It’s a tall order for a clinic perpetually short on resources. So, Jones prides herself on being able to do a lot with a little.

“I probably spend an average of about $100,000 a year to run this clinic. But we put out about a million and a half in services,” Jones said. “I’m cheap. I’m real careful about the money we use.”

It’s ironic, Jones said, that Alabama lawmakers have not done more to ensure that clinic patients are benefitting from taxpayer dollars being squandered elsewhere. For example, in 2019, AL.com, the state’s largest news organization, reported that Etowah County Sheriff Todd Entrekin pocketed $750,000 of local, state and federal tax dollars meant for food for jail inmates. He built a beach house with that money.

“I could run my clinic on that,” Jones said, recalling her initial response to that pilfering of taxpayer funds.

Jones, who is white, said her clinic provides care for Blacks, whites, Latinx and Asians, a demographic that reflects the county’s make-up. She has a patient whose husband died before she was old enough to be eligible for Medicare, the federal insurance program for seniors. “He had a heart attack at the beginning of COVID, and she fell apart. But she’s working at Riverview, one of the local hospitals, now. She’ll be insured next month.”

Other clinic patients are waiting to hear whether they’ve qualified for Supplemental Security Income, a monthly federal payment to those deemed too disabled to work. Some patients, she said, are people who haven’t ever worked a steady job and struggle to survive on their own, with support from kin and friends.

“I don’t always agree with them,” she said about patients’ who decide against seeking work. “But I love them.”

When people don’t have access to a clinic like hers, they’ve often rely on hospital emergency rooms, including for basic, less expensive preventative health care that otherwise would be offered in a doctor’s office. Kaiser Health News reported that unwarranted visits to the emergency department costs billions of dollars per year, and 12 times more than a regular visit to a doctor.

In Alabama, Medicaid only pays for an emergency department visit if a patient reasonably believes that, without it, that individual would suffer serious harm. Patients are forced to discern, on their own, whether they risk bodily harm, which is another reason Jones wants to see more providers serving in spaces like her clinic.

“There’s always going to be a need for what we do,” Jones said.

PAULA TERRY, A HOTEL LAUNDRESS, ALSO IS IN THE “MEDICAID GAP”

A stack of unopened bills was on a table in Paula Terry’s home in rural Ashville, Ala. Somewhere in the pile, on that day in May, was an emergency department invoice that Terry wasn’t planning to take a peep at. She knew she couldn’t cover whatever she owed for showing up in the ER with COVID-19.

Terry was clear that going there, where she’d been diagnosed and treated months ago, would be expensive. But because she’s uninsured, she figured she didn’t have another choice. She’d been in bed for two days with a fever of 103. “I couldn’t hardly get up. I felt so bad,” said the 52-year-old, who has high blood pressure and was worried that, if she waited any longer, she’d have a stroke or some other crisis.

“I fall in the [Medicaid] gap,” she said, noting her place among the roughly 400,000 to 460,000 working Alabamians earning too much to be eligible for Medicaid health insurance for low-income people but too little to afford private insurance.

“They sent me home,” Terry said, of her trip to the ER, “because there wasn’t anything else to do. So, I suffered through it, took Tylenol.”

What she wanted was to be able to get back to work. If she didn’t work, however, she and her husband would be eligible for Medicaid. That was a tempting thought, especially as those ER bills kept arriving in the mail.

The reality is that Alabama’s spending on unemployment and welfare benefits ranks among the lowest in the nation. Without the added funds from the federal pandemic relief package, Alabama paid between $45 and $275 each week in unemployment benefits. “I wouldn’t be able to pay my water bill, my power bill. I have to work. There’s no question,” Terry said.

Once she got better, she did return to washing linens at a Holiday Inn about 20 minutes away in Gadsden.

“I love my job,” said Terry, who relishes the camaraderie. “You know us females. We do a lot of talking.”

Terry has been with the hotel for three years and works as a part-time laundry attendant with a cleaning crew that’s entirely part-time and female. According to job postings, laundry attendants in Alabama earn an average of $9.50 an hour, which is above Alabama’s $7.25 hourly minimum wage.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Terry and her husband, a construction worker, were both without work as their industries shuttered. Her husband has not found work since. So, they live on Terry’s income. She keeps them on a tight budget. The cost to see a physician and refill her blood pressure medication costs about $140 every other month. That expense is significant, she said, and leaves no room for other medical needs.

“It’s hard. Back during the beginning of the pandemic when nobody was able to work … and unemployment [payments] were running behind, we just had to wait until money came in,” Terry said.

Overwhelmed by unemployment claims at the beginning of the pandemic, the Alabama Department of Labor struggled to make on-time unemployment payments to hundreds of thousands of jobless Alabamians. Last summer, the state required people to drive to Montgomery where they had to wait outside the department for its assistance filing claims. Now, Gov. Kay Ivey, a Republican, has decided to end Alabama’s participation in the federal funding program that allows an additional $300 each month for claimants.

Terry said she and her husband will have to tighten their budget again.

She doesn’t care about politics, she said. She wants Medicaid expansion to come to Alabama. She wants more affordable medicine, better access to doctors.

“I just wish,” Terry said, “they’d do something for folks like us.”

[Related: Alabama’s Essential Workers Lack Access to Basic Health Care, Services, Report Says]